‘An artist is never poor’

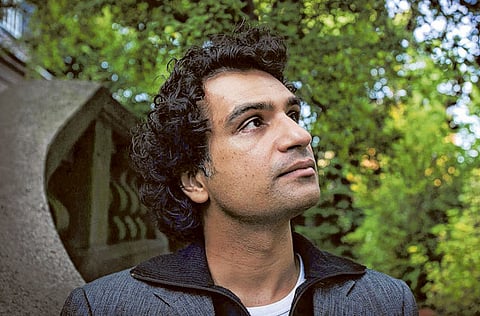

Nadeem Aslam, whose The Blind Man’s Garden has just been published, says many ‘9/11s’ have torn through Pakistan and its women

Nadeem Aslam was years into his second novel when the September 11 attacks took place. “Many writers said the books they were writing were now worthless,” he recalls. Martin Amis, for one, felt his work in progress had been reduced to a “pitiable babble”. But Aslam’s saddened reaction to 9/11 was one of recognition. “I thought, that’s “Maps for Lost Lovers” — that’s the book I’m writing.”

The link might seem tenuous to a novel set many miles from the twin towers or Bin Laden’s lair, in an almost cocooned urban community of Pakistani migrants and their offspring in the north of England, where Aslam grew up from the age of 14.

The novel was almost pastoral in its tracing of the seasons, with riffs on jazz, painting and spectacular moths. Each chapter was as minutely embellished as the Persian and Mogul miniatures Aslam has in well-thumbed volumes on his coffee table.

But the plot turns on a so-called honour killing, as an unforgiving brand of Islam takes hold. In his view, and above all for women, “we were experiencing low-level September 11s every day”.

“Maps for Lost Lovers”, which took 11 years to write, and was published in 2004, won the Encore and Kiriyama awards (the latter recognises books that contribute to greater understanding of the Pacific Rim and South Asia). It was shortlisted for the Dublin Impac prize and longlisted for the Man Booker prize.

His debut, “Season of the Rainbirds” (1993), set in small-town Pakistan, had also won prizes, and been shortlisted for the Whitbread first novel award. The books confirmed Aslam as a novelist of ravishing poetry and poise — admired by other writers including Salman Rushdie and A.S. Byatt.

In “Where to Begin”, an essay for Granta’s Pakistan issue in 2010, Aslam wrote that literature is a “public act”, and a “powerful instrument against injustice”. Yet his heart is in revealing how his chosen subject matter — whether, he says now, “honour killings, female infanticide or Afghanistan” — connects “to a flesh and blood human being”.

Looking back from the point when Western forces began bombing Tora Bora in October 2001, “The Wasted Vigil” (2008) traces decades of Afghan history, through Russian, American and British outsiders and a young Talib, all of whom had lost something there, in a”companionship of the wound”.

Largely mapped out before 2001, the novel was fed by conversations with 200 Afghan refugees in Britain, and travels in Afghanistan. While the novelist Mohammed Hanif praised it as a “poetic meditation on the destructive urges that bind us together”, some were uneasy about its twinning of beauty and brutality.

For Aslam, “beauty is a way of mourning the dead”, while his lament for lost art, such as the Bamiyan Buddhas blown up by the Taliban, “in no way takes away from the deaths”.

Aslam, who turns 47 in February, has a certain intensity, speaking over jasmine tea in an airy, architect-designed loft in London’s Belsize Park, which he has just rented for a year. He lives alone, working for long periods in unusual seclusion, and his almost breathless leaps between subjects might be making up for months of silence.

Yet he follows the news avidly (“the most emotional programme on television”), and travels yearly in Pakistan, “now I can afford it”, with local travel-writer friends.

“The Blind Man’s Garden”, his fourth novel, published by Faber on February 7, opens soon after September 11, almost where “The Wasted Vigil” left off. But while the previous novel had no Pakistani characters, this one traces the spilling over of the Afghan war into its neighbour.

People forget, Aslam says, that “Pakistan has paid a huge price for the war in Afghanistan”. Since 2001, “upwards of 30,000 people have died in terrorist, jihadi violence. That’s one 9/11 every year.” Of the CIA drone attacks since 2004 on northern Pakistan, “only one in 50 ‘surgical strikes’ is killing a militant. So they’re taking out husbands, wives, children as ‘collateral damage’.”

The main setting is Heer, a fictional Punjabi town in Pakistan, in a horse-breeding region whose “fake history” he filleted from imperial gazettes. Two foster brothers in their 20s, in love with the same woman, cross the border into Afghanistan, one of them a medical student volunteering to tend war casualties, in a novel partly about idealism, self-sacrifice and the temptation to torture.

One brother is held prisoner first by an Afghan warlord, then by US forces. While warlords deliver random captives up to the Americans for cash as “suspected terrorists”, the inhuman logic behind September 11, that “there are no innocent people in a guilty nation”, is applied wholesale in the war on terror.

The novel was written in his brother’s cottage in the Peak District, a bus ride from “Heathcliff country”. Aslam concedes that “Wuthering Heights” may have entered his novel “subliminally” — if not in its anguished love triangle, then in its characters’ “youthful intensity”.

In an echo of Michael Ondaatje’s fiction (“one of the greatest writers”), one character has his trigger fingers sliced off by a warlord. Aslam produces a photograph of his own taped-back fingers, as he tested the dexterity of maimed hands.

Another is near-blinded by a warlord’s thumb dipped in crushed ruby dust. Aslam says he taped over his own eyes “24/7”, for three week-long periods. Apart from ending up “covered in bruises” and losing consciousness briefly after a fall, “I had nightmares and visions, everything was intensified”. What he missed most was painting, which he does every week, sometimes visualising scenes for his fiction.

His first two novels had protagonists in their 40s or over. “Now I’m older, I’m writing about the young,” he says. “We underestimate the grief of the young. They’re brought up with a set of ideals, then sent out into the world. How are you going to cope? Are you going to be corrupted, or are you going to say no, a heroic life is possible?”

While the boys’ father runs an Islamic school, turned into a jihadist bootcamp by extremists (“Schools are battlegrounds in Pakistan,” Aslam says), the brothers’ idealism is based on humanist values found in Islam.

For Aslam, a “secular atheist”, one advantage of growing up in Pakistan is an extended family. “I have 50 first cousins, and every person has their own kind of belief or disbelief. I always knew there was no one way of being Muslim, but a whole spectrum.”

He was born in 1966 in Gujranwala, a Punjabi town north of Lahore. His father was a communist, poet and film producer. Through his family, “I learnt about political commitment and the life of the mind, and that an artist is never poor.”

His mother’s side were “money-makers, factory owners — and very religious”, some versed in storytelling, music and painting. His parents, whose marriage was arranged, may appear an odd couple (their quarrels recur in his fiction) but “they still love each other, despite their personal differences. As a novelist, it’s a gift.”

The adult in “Season of the Rainbirds” who destroys children’s playthings as idols, was based on a maternal uncle, an adherent of a “strict, unsmiling sect” of Islam, who smashed his nephew’s toys. As Aslam later wrote in “God and Me”, a fragment of memoir in Granta in 2006: “My uncle’s version of Islam was the same kind practised by the Taliban regime in Afghanistan three decades later.”

That first novel was a child’s-eye view of a violent shift in society, and the spread of extremist sects, compounded by a crackdown after an attempt on the life of the ruling general — as happened in Pakistan in 1982.

Aslam was 11 when General Zia ul-Haq seized power in a military coup in 1977, with a drive for “Islamic values”. “He changed the entire texture of Pakistani life,” Aslam recalls. “People began to give children Arabic names. There were public floggings and hangings.”

His mother’s family approved. His father’s were appalled. After the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, when refugees flooded into Pakistan, covert US and Saudi aid to the Afghan Mujahideen was channelled through Zia’s regime.

“Whatever Zia did before Christmas Eve 1979 was condemned. On Christmas Day, he became a hero. This is how things spiralled and the jihadi mindset emerged. My father and uncles, radical communists, were among those who said don’t do this, don’t encourage this mindset.” As Zia clamped down, “journalists and writers were arrested, or had to leave the country in fear”. One uncle was “taken away and tortured”.

Once the Soviet soldiers withdrew, and US interest waned, the Taliban rose. As Aslam sees it, “ten years later 9/11 happened and half the planet woke up. They had no idea it came out of the Cold War.”

Later, teaching at George Washington University in 2009, Aslam would pass the White House, and think “how words on grey paper in the 1980s became fists, electric wires and instruments of torture which broke members of my family and friends”.

When he said as much in a US interview, “it was seen as anti-American. But these were the results of the Cold War. These decisions, with the collusion of Pakistani rulers, ended up breaking and killing people.”

His family fled into exile in 1980, settling in Huddersfield, west Yorkshire. Aslam, whose mother tongue is Punjabi, had gone to Urdu-medium schools, since English education was for the affluent few. His first-published story, when he was 13, was in an Urdu newspaper, and Urdu literature remains his “first point of reference”.

In Britain as a teenager, his self-imposed crash course in a language he could barely speak was to copy out entire novels by hand. He lists Nabokov’s “Lolita”, Gabriel García Márquez’s “Autumn of the Patriarch”, Bruno Schulz’s “The Street of Crocodiles”, Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” and Cormac McCarthy’s “Blood Meridian”. “That’s how I learnt English, looking at the sentences,” he says.

He excelled at science, “where all you need is facts”, and studied biochemistry at the University of Manchester. But in his third year he dropped out, “when I realised my English was good enough to do what I wanted”.

He sent his first-novel manuscript to André Deutsch, finding the publisher’s address on V.S. Naipaul’s “A Bend in the River”, where it was swiftly accepted by Naipaul’s then editor.

He was 23 when copies of Rushdie’s “The Satanic Verses” were burnt in nearby Bradford, and the Valentine’s Day fatwa was imposed. For him, it echoed what had long been happening in Iran and Pakistan, “but I understood it was a community beginning to assert itself”.

Scrutinising a similar community in “Maps for Lost Lovers”, he was “trying to understand what maleness is”. He recalls being horrified at a senator in Pakistan who “defended burying women alive who bring dishonour to their men”, and senses a link to youths’ susceptibility to terrorist logic. As he later said of the London suicide bombers of July 7, 2005: “Those boys who blew themselves up, boys like that were beating their sisters.”

“Nothing in that novel was made up,” he says now. “I lived in that community and my family still does.” His late maternal uncle, an Islamic missionary to England in the 1970s, helped found the Dewsbury mosque where the London bombers “were radicalised. I didn’t see it coming, but I could imagine the paths these boys took.”

Yet he does not blame his characters for their inwardness. “You do want to go out into the world, but there are signals and you withdraw, and what you have is your religion — a source of strength.”

Once, he recalls, on his way to visit his mother, who was ill, “I opened the paper to find Martin Amis’s ‘thought experiment’: that Muslims should be stopped from travelling. I broke into a sweat. They would stop me from getting on a train to see my sick mother because someone who looks like me has carried bombs.” He appears stricken. “When I criticise Islam, it isn’t in that tenor.”

Aslam makes the startling assertion that he has “11 more novels to write” — all already mapped out. Now writing a novel “about Pakistan’s blasphemy laws”, he has also been working for 15 years on a trilogy based on his father, whose pen name is Wamaq Saleem, and who appears in his son’s oeuvre as “the great Pakistani poet” — a son’s loving fulfilment of his father’s frustrated ambition.

He barely pauses between books. “I’ve more or less realised my writing has cost me almost everything,” he says. “Sometimes friendship, love — because there’s not enough time to be with people, and never enough money. Work can take so much out of you, with 12- or 13-hour days. A study is a laboratory first — then a factory.”

His raw material is in “about a hundred” notebooks, over 25 years. An American soldier in “The Blind Man’s Garden” has a tattoo that reads “Infidel” in Arabic, as though a boast. The shocking image came from a magazine photo of a real soldier that Aslam duly taped into his notebook.

His fiction is sparked by “anything that distresses me”. Paper is the “strongest material in the world. Things under which a mountain will crumble, you can place on paper and it will hold: beauty at its most intense; love at its fiercest; the greatest grief; the greatest rage.”

Yet as soon as he starts writing, “I begin to think of it in another manner: what caused it, and, beyond the despair, what is the moment of hope in here?” He looks agitated. “I must find that.”

–Guardian News & Media Ltd