Dubai: From hosting international events to sponsoring the world’s best teams, the UAE has built its brand as a tourist destination and transit hub predominantly through sport.

But why? Is it working? And what are the future challenges of this strategy? Gulf News spoke to leading academics on the subject.

As a developing nation, which formed the union in 1971, the UAE has been quick to diversify its economy away from oil production, and sport arguably lit the touch paper to such explosive growth.

Simon Chadwick, a professor of Sport Business Strategy and Marketing at Coventry University in the UK, said sport was an obvious vehicle to build the UAE’s brand.

“Sport brings immediate and widespread recognition,” said Chadwick. “It draws in peoples’ attention. Part of building a brand involves getting people to look at you and talk about you.

“Because of sports’ global appeal, being associated with it inevitably raises awareness and prompts recognition in a way that say, investing in a new road network wouldn’t.

“At a fundamental level it’s about global recognition and acceptance. Not too many people will have known where the UAE is, but this has now changed.”

Sport has affected urban development and the hotel, airline, retail and tourism sector domestically. But James Dorsey, a senior fellow of international studies at Singapore’s Nanyang University with particular focus on the link between sport, politics and society in the Middle East, says the strategy has far-reaching effects globally, branding it a “soft power” in international relations.

“The world of diplomacy has fundamentally changed,” he said. “It’s no longer a world that is exclusively diplomats talking to diplomats and government agencies talking to government agencies; it’s a world in which cultural diplomacy and public diplomacy is of equal importance.”

Mahfoud Amara, a lecturer in Sport Policy and Management at Loughborough University, in the UK, even suggests that the UAE’s eagerness to support European sport during the recession has widened its place at the international table.

“Investing in European countries during the economic crisis gives the UAE credibility, making them a credible actor in the international community,” he said.

Tangible benefits of this strategy in terms of tourist numbers, flights and hotel bookings, may justify the expense, but Dorsey says the full value of this approach may never be calculated.

“It’s hard to measure, as a diplomatic service a cost-benefit analysis is tough because a lot of value isn’t really tangible,” he said. “It’s only evident when put to the test. But without it, to some degree the UAE may or may not have larger representational problems.”

Chadwick said that one kick-back that must be assured is the UAE’s ability to develop its own athletes, in order to inspire the next generation, foster a greater sense of community and promote a healthier lifestyle for a fitter workforce and economy, particularly with the prevalence of diabetes and obesity in this region.

“It’s essential that the strategy doesn’t just focus on elite sport, it also needs to focus on grassroots sport, building social cohesion through sport and creating a culture in which people want to watch and participate.

“There needs to be a holistic strategy and a coherent policy on sport. Sport can do so much more than contribute to nation building. Get the strategy right, and you can address health issues while promoting social cohesion, building the country’s brand, and boosting elite level performance.”

Amara said criticism of GCC countries harvesting elite athletes from Africa and giving them passports, was unfair at this stage in development.

“GCC countries are now in the phase of nationalisation, but they are small countries with small populations and may still continue with naturalisation. They must continue to maintain presence at elite level while also developing homegrown talent.”

In terms of challenges, all the academics pointed to criticism of Qatar’s 2022 Fifa World Cup bid, as a downside of publicity through sport.

“It’s a double-edged sword,” said Dorsey. “Once Qatar had won the bid to host the World Cup they thought they were seated, but what they didn’t understand was that while it gives them leverage, it gives others leverage too.”

Amara agrees: “The more you publicity you get, the more exposed you are to criticism. That’s the price you have to pay. If you want to be seen as progressive and liberal, you have to be accountable to your brand values.

“Some citizens will see this openness as a threat with regards to cultural identity, so you also have to be aware not to be too open, or at least maintain your identity.”

Chadwick said there were positive signs from Qatar, however. “Qatar was naive to think they wouldn’t be criticised,” he said. “But there is evidence now to suggest that things are starting to change and countries do realise that with profile, status and glamour comes criticism and they are managing their reputations a lot more. From Qatar, eastwards countries are learning and realising there are upsides to the development of sport but a lot of downsides too.”

Questions marks will continue to surround the ability of developing countries to sustain these strategies, which are dependent on economic and political stability; especially with competition from other nations cropping up that are also keen to build their brand and diversify from finite natural resources, like Azerbaijan, whose tourism board sponsors Spanish football club Atletico Madrid.

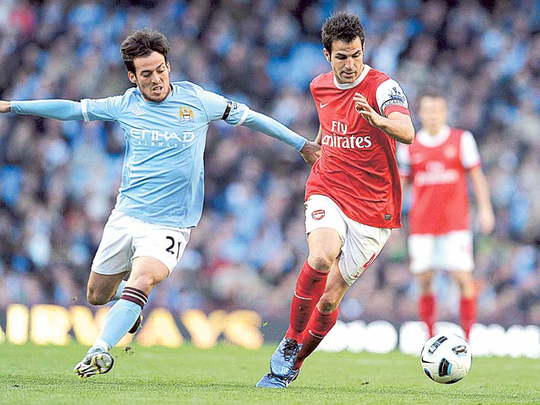

More specifically in football, Dorsey suggests Arab backed clubs in Europe like England’s Manchester City and France’s Paris Saint Germain, may not enjoy similar success in the future with the introduction of Uefa financial fairplay, weakening the benefits of fast-tracking brand growth by funding overseas clubs.

“Financial fairplay is aimed at creating a more level playing field, thus neutralising a club’s financial muscle,” he said. “What Man City and PSG were able to do in the last three years, they likely won’t be able to do in the future.”

But despite inevitable bumps on the road, Chadwick predicts a bright future for the region.

“This is all part of a more general eastward shift in sport,” he said. “You only have to look at the way the Formula One calendar has changed over the past 20 years to see that sport is chasing the money.

“The situation is slipping away from Europe very fast and I don’t think Europe is alert to the changes that are taking place and it isn’t really responding to them in a co-ordinated or meaningful way.

“Asia will become the dominant sports model in the future with state intervention linked to profile, reputation and status, and a strong commercial sector alongside.

“As peoples’ disposable income increases, entertainment and leisure time becomes more important and places like Dubai will see more people engage in sport and it will become even more popular there as their own icons emerge.”