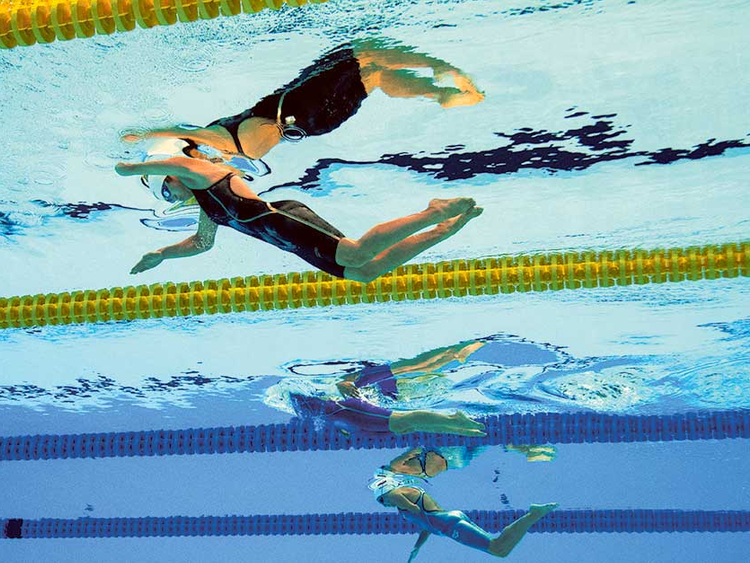

Rio De Janiero: Saws buzzed, drills rattled and sewing machines hummed as Victor Scody, a swimmer from Mauritius, wandered into the Paralympic repair workshop on Tuesday morning with a problem — or rather, problems.

The socket of his artificial leg needed an adjustment. It felt too loose in one area, too tight in another, and he felt too tall overall. The imbalance was hurting Scody’s back.

Examining the prosthesis, Julian Napp, a technician, sounded hopeful.

“Maybe we can change something,” Napp said. “Maybe.”

When athletes arrive at the Paralympic Village, they care most about three things: internet access, food and the location of the repair shop, which the German company Ottobock has operated at every Paralympics since 1988.

That the workshop shares the same roof as the athletes’ dining hall underscores its importance. They cannot perform without proper nutrition. They cannot compete without their equipment.

So they flood the workshop, arriving in waves — after mealtimes, especially — with wheelchair tires to pump, axles to mend, frames to weld. More surgeons than mechanics, the technicians liken themselves to a pit crew at an auto race. Except that pit crews know which car they are servicing, when that car is going to pull in and which language they use to communicate with the driver.

“Every time the door opens,” said Peter Franzel, an organising director at Ottobock, “we get a surprise.”

The unpredictability of the job demands an array of skills from the technicians, beyond an expertise in prosthetics, welding or wheelchairs. Specialists who hail from 29 countries and speak 26 languages, they must be calm enough to handle the pressure of a workplace that handles at least 100 repairs every day. They must also be creative and intuitive enough to solve problems they have never seen before.

One of the most challenging requests of the entire Paralympics arrived on Monday night, when the champion British cyclist Sarah Storey arrived holding a thin, circular hunk of metal, a few centimetres in diameter, that had recently snapped off her spare bike. Whatever the part was — not even Storey knew, though she believed it related to the braking mechanism — it had warped when it detached.

Without the bicycle for reference, and reluctant to weld a piece that small, the technicians improvised by making a mold and then constructing a replacement part out of carbon fibre. Storey did not need the spare bike on Wednesday, when she won gold in her time trial, but she was grateful for their assistance.

“Even if you don’t have any wheelchair requirements or the prosthetic limbs, someone like me can turn up with this random piece and say, ‘Help!’” Storey said minutes after she picked it up Tuesday. “That’s the beauty of the service.”

The service, which is provided to all athletes at no cost, extends to each venue, where on-site technicians change tires, tighten screws and adjust alignments. Only a few nations — including the United States, Germany and the Netherlands — brought their own prosthetists to Rio, but athletes from those teams, which are among the largest at the Paralympics, still have access to the workshop. So do the official team prosthetists, like the US team’s Francois Van Der Watt, who are granted privileges to work and make repairs there.

From previous competitions, Franzel said, Ottobock has learned how much of what to stock. Each station at each venue carries basics like nuts, bolts and glue, but also a batch of sport-specific equipment.

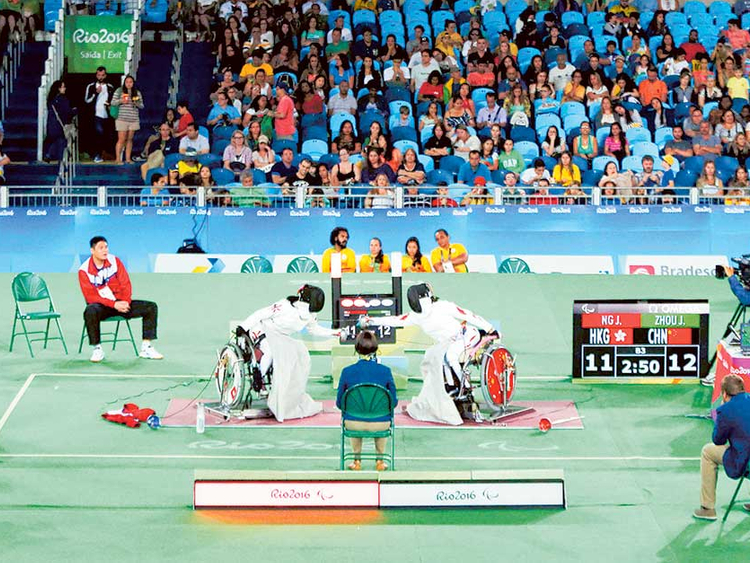

For boccia, a ball sport similar to bocce, the prevalence of power wheelchairs requires extra fuses. Wheelchair tennis players cycle through tires quickly, so spares are a must. At arenas hosting wheelchair rugby and basketball, the roughest of the Paralympic sports, welding units are available to fix damaged frames.

The more complex repairs are saved for the main facility, which occupies about 2,700 square feet of Ottobock’s 7,000-square-foot space in a walled-off section of the dining hall.

The space houses some of the 15,000 spare parts, ranging from running blades to knee joints to artificial leather, shipped here in advance; a room devoted to welding and another for molding plastic; and a central area, with three workbenches and a variety of machinery, where on Tuesday morning specialists hustled to complete jobs.

In the back, Ricky Benzing said he was gluing temporary sockets onto prostheses for a discus thrower from Niger. Off to the side, Jan Snytr sawed a metal bar, which would be used to lengthen, and stabilise, a frame that a Palestinian shot-putter needs for support. When the Palestinian coach, Mohammad Dahman, arrived to retrieve it, he shook Franzel’s hand.

“Hopefully, he can throw the ball a little farther,” Franzel told him. “Maybe he’ll set a Paralympic record.”

“I hope that very much,” Dahman said.

Through Thursday, Ottobock had made, or was in the process of making, 2,970 repairs, with the vast majority (2,435) involving wheelchairs.

“I’m always happy if the numbers aren’t good because there are less problems,” Franzel said. “In a perfect games, we’d be playing cards.”

The repair total does not include the broken sunglasses brought in by one chair owner who Franzel offered to help. For obvious reasons, the technicians prioritise fixing equipment needed for competition, although they also service everyday wheelchairs and prostheses, a boon for athletes from countries that are poorer or lack expertise in the field.

It benefits the Rwandan athlete who was using a prosthesis that seemed like it was 50 years old, one specialist said, as much as Liam Malone, a bilateral-amputee sprinter from New Zealand who receives his blades from a New Zealand artificial limb service that Malone said lacks experience in sport prosthetics.

“All I can do is put in a wedge and take out a wedge,” Malone said last week. “That’s all I can do. Dude, look, I’m holding my legs together with tape. Me and them, we try to figure it out. But none of us really know.”