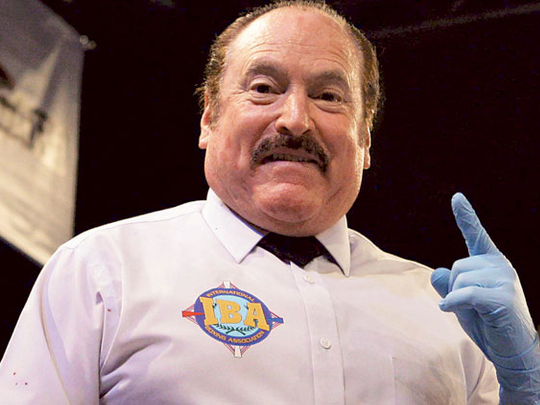

Dubai:For more than 30 years he’s had to preside over some of the ‘baddest’ men on the planet. But when you meet Steve Smoger, boxing’s invisible man, you’d be surprised to discover that, despite having had to absorb so much heavy hostility at close quarters, he’s one of the nicest and most down-to-earth guys you could ever meet.

Smoger was the third man in the ring when Bernard Hopkins pulverised Felix Trinidad at Madison Square Garden on September 29, 2001, and when a certain Mike Tyson destroyed Brien Neilsen in front of 40,000 screaming fans at the Parken football stadium in Copenhagen, Denmark, the same year.

He was the arbitrator who famously allowed Kelly Pavlik the chance to regain his composure after being violently punished by Jermain Taylor early in the fight, and go on to sensationally win it with a seventh-round technical knockout.

There are few fighters in the world worth a mention on who Smoger has not officiated, and even fewer fights. The New Jersey native has become a regular on the Dubai boxing scene, where he has witnessed Emiriti fighter Eisa Al Dah score victories over Ignasi Caballero and Miguel Angel Munguia from close quarters.

Gulf News caught up with him during his most recent foray to the Emirates.

Gulf News: Steve, you’ve been in the fight game over 30 years now. Can you tell me how and when it all started?

Steve Smoger: I began my officiating career in the sport of boxing as an amateur official with the United States of America/Amateur Boxing Federation (USA/ABF) in 1974. In 1982 and I received my probationary licence from the New Jersey State Athletic Commission, headed by then-commissioner Jersey Joe Walcott. It was a significant date because it’s the 30-year anniversary of Walcott’s legendary first fight with Rocky Marciano. I was sitting on his daddy’s knee at ringside and I always told Jersey Joe that he wish I had been old enough to appreciate that historic match. He loved the story and chose that date to licence me as a boxing official. The rest, as they say, is history.

What has been your most memorable boxing moment?

There’s been a lot. I’ve been really, really blessed. But, of late, I have to say the most historic with the greatest impact and timing was when Bernard Hopkins fought Felix Trinidad for the IBF, WBC and WBA Super Middleweight titles at Madison Square Garden. It was the first major sporting event in the world after 9/11 and the feeling at the Garden was just unbelievable.

It was a packed house, with many of the survivors from the attacks in the front rows. Don King was the promoter and he invited those survivors who felt well enough to attend to show his affection. There were police widows and injured firefighters seated there; it was surreal, it gave me goosebumps.

The fight itself was highly anticipated and Don King donated a fire-apparatus truck to the station. Every aspect of it was so emotional, so memorable because the emotions following the event and the fight itself, where Hopkins prevailed by a 12th-round TKO. That was a highlight moment. Of course, that same year, 2001, there was Mike Tyson versus Brian Nielsen, with 40,000 at the Parken soccer stadium in Copenhagen, Denmark, which was a major event too.

Could you put your finger on the best fight you have ever refereed?

My keynote fight that put me on the map was in April of 1988: Simon Brown against Tyrone Trice for the IBF Welterweight title. In the ninth round, Trice got hit and fell like a tree. If you ask what is the most outstanding feature you’ve seen in the ring, it’s the ability for an injured fighter to get up in ten seconds.

I’m amazed that Trice got up. And he gave me five rounds after that. Brown stopped him in the 14th — a combination dropped him and he fell in my arms. I would say that the most amazing aspect of boxing is the ability of a human being to get up when he’s hurt.

There was Kelly Pavlik’s KO of Miranda in round seven in 2007, and then in September, Pavlik’s destruction of Taylor. I did Kelly Pavlik back to back, at his finest hour. They were some of the best fights I’ve seen.

You’ve seen a wide range of boxers in action at close quarters, which boxer would you say defined the sport?

Each era had their share of great fighters. In the late 80s and 90s, I would say James Toney stands out. I had James when he was a middleweight, I had him when he won the cruiserweight title and then I had him when he beat John Ruiz for the heavyweight title. So you grow with the fights. You see them in all stages of their career. I can’t single out any one recent fighter that really solidifies boxing.

What is the protocol of referring a fight. How do you react when things appear to go wrong?

Refereeing is the art of judgment and movement in the ring. It’s the principle of knowing ‘when to say when’, of being able to perceive when to stop a fight. You can never unstop a fight. I am guided by that principal.

I began my career in the fight game as an assistant coach at the Atlantic City Police Athletic League in the late 70s, when I was at law school, and I guess I saw what the fighter put in and how hard they train.

So you can’t unstop a fight; once you wave it off, it’s done, so I like to see a fight go to its natural conclusion and let the fighters decide the fight. So, in that regard, I have developed a keen sense as to ‘when to say when’, and to observe; I call it loss of presence.

When a fighter loses his or her ability to defend themselves, then safety becomes an issue.

Do you have any likes or dislikes when it comes refereeing a particular weight class?

It was said that, for my stature, I would have difficulty with heavyweight, but it’s just the opposite because they listen. It’s the rookies, the first-time starters who give you the most trouble because you don’t know which way they’re going to move as they’re still learning. The punches are wild and they’re not used to verbal commands like ‘punch out’, ‘let ‘em go’ or ‘break’. Not that they don’t follow you, it’s just that they’re awkward. The more experienced the fighter, the bigger the event, they listen.

Now that you are quite familiar with the boxing scene in Dubai do you think it’s going in the right direction?

Absolutely. The eyes of the boxing world truly are on Dubai because Dubai’s reputation precedes all activities. The greatest horse racing in the world occurs in Dubai. You have the tennis champions, the golf, so people are expecting that they are going to see a high level of boxing in Dubai because everything you do here is of a high level. I have to give credit to people like the local Prince Amir Shafipour for really endeavouring to bring world-class fighting to Dubai.