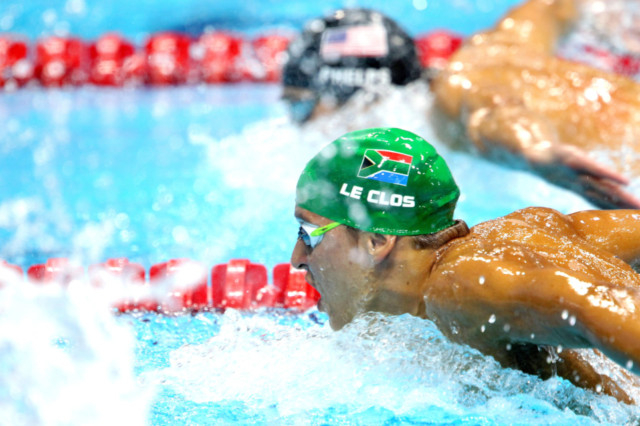

Dubai: When Chad le Clos beat Michael Phelps in his pet event, the 200m butterfly, at the London Olympics last year, he graduated from a swimmer into a fantasy. The moments of astonishment by Chad and his father Bert have been recorded by the BBC and archived in YouTube. They will go down as the reactions that followed perhaps the greatest upset in swimming history.

Phelps’ dream of winning eight gold medals was dashed when Le Clos, seemingly hit on a turbo reserve of power in the last 10 metres of the race, which his rival had been leading by a fingernail length up to that point, to overhaul the man he had hitherto idolised.

In the minutes that followed, Bert le Clos became even more famous than his son, judging by his exclamations of joy, hysteria and the uncontrolled tears that flowed down his face. After sanity was restored, the world began to scrutinise the magnitude of Chad’s achievement.

The bar of excellence had been set very high, unwittingly so, but this is what happens when you beat a a legend who hasn’t lost his specialty event in a decade. The South African challenger, blessed with a wealth of precocious talent and ambition, realised after the Olympics that, in the world of competitive swimming, he was now a hunted man.

Underlining the challenge

Le Clos also realised that, despite knocking Phelps off his pedestal, people did not believe in him. He took these thoughts to the pool and they stayed locked inside his head as he swallowed up lap after lap, in exhausting practice sessions, cutting through the chlorine-laced water. He was paying a heavy price for winning.

“There has been a lot of pressure on me since that day in London,” Le Clos told Gulf News. “I have been carrying a target on my back after beating Phelps. There’s pressure from everywhere. Usually, I was looked upon as the underdog, but this year, at the world championships, it was different.”

The hunter had become the hunted.

Le Clos has always trained to win. It is not just the way of an Olympian, it is in the DNA and ethos of a South African sportsman: finishing second is never an option. The scenario that presented itself was, however, a study in contrasts. The mental make-up of a top-flight competitor may carry signs of extreme vulnerability, but an Olympian will always ensure that his body does not betray the insecurities that afflict the mind.

So he sat perched on a high chair at the Hamdan Sports Complex in Dubai, after a punishing workout in the pool, the muscles in his arms and chest still quivering from the stress they had been subjected to. His head was held up in an oddly proud way, like a soldier sitting on a horse, when he indicated: “There are pressures that are necessary for a world champion. Nothing new to that, but it was news to me. I have been trying to find where I was this year. It has been hard in public and in training to make that change.

“The biggest thing is not my mental approach. That hasn’t changed. It’s more about coping with the fact that when I enter every race now I am supposed to win. I accept that favourites are supposed to win, so that’s the biggest thing.”

The pressure game

Too much pressure for a 21-year-old who has the world at his feet?

“I think I found it hard after London,” Le Clos admitted. “I didn’t train for about three to four months. I focused on doing things that I never had a chance to do. I was enjoying my life. When I started training again, I injured my right shoulder in Dubai last year. I stopped swimming in Doha because my shoulder played up again and frustration began to set in,” he said.

The distractions

“January to March weren’t very good months for me. I was struggling to be myself, to adjust to everything. Slowly, however, things began to fall into place. Barcelona was profitable as well as Eindhoven. I set a few world records. This made me stronger as a person.”

The poster boy of world swimming found that his time had been divided into long periods in the pool and phases where he had to network off it in order to leverage this newfound equity that had been thrust upon him by virtue of beating the greatest ever swimmer and Olympian. It was an uncompromising equation. These were not the alternatives that Le Clos had wanted. “I take a lot of time for my supporters and sometimes you just don’t understand how much it takes out of you. My coach kept reminding me that there are also races to swim and to win,” he added.

He began to develop a new identity after doses of various insights were injected into him by his family and coach. He was essentially a swimmer and these priorities were to be examined in the pool. The graduation into a role model for thousands of South Africans would have to be assessed as well. Training, winning and losing held more significance. This would be examined time and again, re-tweaked and re-programmed till there was nothing left but a finely-tuned machine that could set the water on fire.

That remains the primary goal, one that will propel him to his tryst with glory at the Olympic Games in Rio in 2016. Le Clos must prove to the world that beating Phelps in London was not a chance occurrence, but dividends that followed the years of investments that he had made in the pool, from the age of 10.

“I have never been afraid to race anybody,” he confessed. “The biggest thing for me is to turn it around when the time comes — press that button. You have to slip the noose in when the moment is right. I always knew in training, when my coach told me to sprint in the butterfly, then I had to do it. If I can’t do it then, there’s a problem. If I can do it in training, then I can do it in a race. You never know who is on form,” he added. “I could be the favourite in every race, but if my opponent is going really fast then I just have to relax and try to win.”

This is why he and his coach Graham Hill insist that the training schedules should be harder than the race itself. They must simulate competitive conditions so that, when the race comes, the sequences begin to fall into place like a puzzle that has been decoded.

Training code

“The programmes are tougher than the race,” Le Clos says. “Graham Hill is a good friend and coach. I also have a training partner who has posted some good results at the world meets. We work closely in the freestyle sets and the medley sets. I need to make sure I am ahead of everybody in order to keep improving. It’s easier to see the changes, but harder in a way that you actually don’t increase that much. Like, for instance, if you go for a time of 59 seconds, then you are improving, but it doesn’t have a way of showing that big in a race. We train for two-and-a-half hours in the morning, two hours in the afternoon — anything from 5 to 8 kilometres in terms of distance. It’s a lot of high intensity stuff. Kicking off for 100 metres in a harder send-off time. These moments help to keep you sharp and in race shape.”

They are also keeping Le Clos focused for his next big goal — Rio in 2016. Le Clos is carrying an enormous weight on his shoulders: the weight of a continent. He has to balance it just right. Then he needs to walk at a steady pace. And, more than anything, he needs to keep going, keep moving, even as the weight bears down.

“I want to swim as many events as I can. One gold, two golds, one bronze, I need the next two-and-a-half years to evaluate my strokes. For example, I am swimming the medleys to improve my other strokes. By 2016, I could be doing the butterfly, individual medley and some freestyle. I am targeting four individual races and the relays as well. So it could be seven to eight races. I do want to get four to five medals and at least three golds. I want to be the best swimmer at Rio. I don’t want anybody to beat me there. I want to reach my capacity and realise it in full.

“It all depends on how motivated you are. Look at [Ryan] Lochte, he’s doing well because he is motivated. The reason swimming is one of the hardest sports is because you have to be in the pool by yourself every day, making that sacrifice. There’s no time to do anything else. The sacrifices are the biggest thing. Making them at an older age is harder, but if you can do it, then why can’t you be the best?” he asks.

Swimming with a bullseye strapped to your back can be daunting. If the rumours are right, then it appears Phelps has already started to train and subject himself to dope tests with the US Anti-Doping Agency in the hope of making a comeback.

“Everybody believes they can beat anybody. I did the impossible by beating Phelps. He hadn’t been beaten in that race in 10 years, so I opened up the doors to other swimmers who can now beat anybody,” Le Clos said.

“What I want to say is that nobody is unbeatable. There’s a kid out there who probably wants to beat me. I train hard and try to be the best that I can be, but I don’t disrespect my opponents. I am not disillusioned either. I know what I need to do: to win at the Commonwealth Games [in Glasgow in 2014]; the World Championships in Russia in 2015 and then in Rio.”

Potential showdown

The shadow of a looming Phelps could become larger as the countdown to the Rio Games begins, even though the American’s coach Bob Bowman has ruled out a return to high-level competition for the most decorated Olympian ever.

“He has an enormous physical presence, an aura of greatness,” testified Le Clos, “But I have never been afraid of Phelps. I say that with respect. I was never afraid to race him. When I am on the blocks, I don’t care who you are, I will always try and beat you.

“The race in London was the perfect race for me. Everything came together, even the touch. It was one in a million for me, but I think of it as a reflection of the hard work I have done in the pool. You make your own luck.”

Le Clos is the archetypal South African: sporting, ambitious, enthusiastic and competitive. It is difficult to say whether he is chasing greatness, or if greatness is chasing him. The answers will be revealed as he leaps over the starting blocks in Rio.

“My dad always taught me never to give up in my mind,” he said. “You can never really beat me. It sounds ridiculous, but I will always come back for you. You can’t beat someone who never gives up. I could lose 100 times to you, but I will always get you. I will die trying. This applies not only to swimming but to my life as well.”

By that logic it seems he has won half the battle already.