Iran scored a major coup when it reached a deal with Turkey and Brazil on processing its low-enriched uranium, in an arrangement that is almost exactly what the United States and its partners failed to get Iran to agree to when they met last year in Geneva.

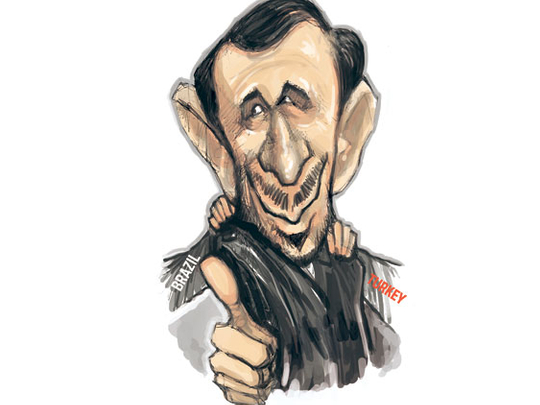

The new plan brings Iran two benefits: it offers a way out of the looming confrontation with the US; but more importantly for President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, it also means that he can reject the offer from the established nuclear powers and choose instead to work with fellow developing nations. This deal is good for him because it does not involve Iran capitulating to American demands, a political advantage he will exploit to the full.

The deal was announced just before this week's G15 summit of developing nations in Tehran and is fairly simple. By now Iran has more than 2,300 kilograms of low-enriched uranium, of which it will send 1,200 kilograms to Turkey. There it will be converted into uranium rods and sent back to Iran. The point is that low-enriched uranium can be further enriched to develop a nuclear weapon, but once it is converted into fuel rods for a reactor it cannot be enriched any further, rendering it safe.

This plan will play very well with the vast majority of nations in the world that are classed as developing nations, and are not rich, industrialised Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development members. They will see this new South-South deal as totally within Iran's rights to achieve, and a welcome reminder that the growing importance of the developing nations is not just limited to their expanding economic power.

This sort of power shift away from the superpower and the few leading nations is happening in many fields. The narrow G8 group of economic powers has given way to the much wider G20 (which actually includes even more silent observers). The Bric (Brazil, Russia, India and China) and Basic (Brazil, South Africa and China) groups of nations have played vital roles in all sorts of arenas, such as the Doha Development Round negotiations on free trade, and the Copenhagen summit on climate change. And there is pressure to expand the Security Council of the United Nations to include more developing nations. The involvement of Brazil and Turkey in the nuclear arena fits into this overall trend, since it was previously very much the preserve of the US and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty nations with declared nuclear weapons.

Iran's new nuclear deal has a long way to go before it will satisfy the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Last year's offer from the UN had the uranium swap as the start of a more complete process, which this new deal seems to ignore. The other main points of difference are that Iran still refuses to be completely transparent in order to prove that it has no nuclear weaponisation programme; and it insists that it has the right to enrich uranium.

Buying time

But whatever else happens, Iran has bought at least six months more time with this deal, even if it goes nowhere. It will take at least that much time for the deal itself to be finalised, and for the IAEA to start its verification procedures, and then to approve the deal if it feels that it meets the international community's requirements. Then the IAEA will need to make its recommendation to the UN, which will debate the issue.

Patrick Clawson of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy sees a big shift in Iran's position, and points out that Iran had three major problems with the UN deal last year: that it was required to transfer 1,200 kilograms of its low-enriched uranium, that the uranium was to be sent in one shipment, and that the uranium would be processed into rods outside Iran. "Iran has now caved on all three," Clawson said, adding that "this is not an end to the problem, but a modest step that helps defuse the immediate crisis".

It is clear that the deal caught the US State Department by surprise, and it has scrambled to catch up while voicing its expected scepticism. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said publicly last week that she expected the deal to fail, and it appears that she is leading the demand for confrontation and sanctions in the administration, while the White House may be looking for a more engaged approach. The Turkish government has claimed that President Barack Obama supports its deal with Iran, despite the secretary of state's opposition.

But as the deal goes through the process of public and IAEA examination, it is certain that Ahmadinejad has managed to pull off a considerable diplomatic coup. He has cemented his position as a significant leader among the developing nations, and his partners in this venture are two very established states: Turkey is a member of Nato and Brazil is an economic powerhouse. And he has dramatically moved the potential of South-South discussions way beyond their present economic focus, into the core of the world's nuclear and military discussions.