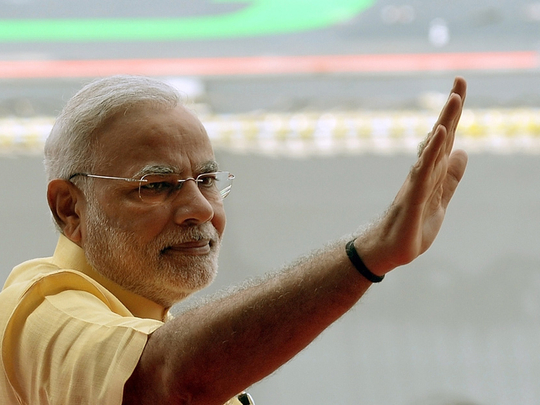

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi has spent much of this month persuading the leaders of the world’s biggest economies to invest in India. He succeeded in large measure with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan and President Xi Jinping of China, whose countries committed investments worth $35 billion (Dh128.73 billion) and $20 billion, respectively. One might expect Modi to bring home an even larger haul from the US, the world’s largest economy, after his meeting with President Barack Obama this week.

In fact, while both sides will no doubt issue all sorts of grand statements about the bonds between their nations and the many areas in which they hope to cooperate, no big-ticket investment deals are in the pipeline.

This is not entirely surprising. For one thing, the US is not a surplus economy like Japan and China, where state-controlled investment agencies can commit billions for reasons that have as much to do with geopolitics as economics. At the same time, Modi has multiple agendas for this trip — his first since the US denied him a visa after religious riots claimed between 1,000 and 2,000 disproportionately Muslim lives in Gujarat in 2002, when he was the chief minister there. Modi is now seeking international legitimacy as much as investment.

It is equally true, however, that the economic partnership between India and the US has hardly lived up to its potential. The two countries share a great deal, from the English language to their democratic political systems, to the huge and influential population of Indians in the US. Yet, while India is the third-largest economy in the world by purchasing power, it ranks as only the 11th-largest goods trading partner with the US and the 18th-largest destination for US exports. In 2013, trade between the two countries amounted to $93 billion. Since 2000, cumulative foreign direct investment from the US into India has added up to a mere $12.7 billion — less than that from Singapore, Britain, the Netherlands and the UAE.

While the reform-minded Modi may carry some credibility with US investors, his nation simply does not. The most significant deal between India and the US in the past two decades was the civil nuclear agreement signed in 2008 by former president George W. Bush and the then Indian prime minister Manmohan Singh. It should have spurred investment from US suppliers of nuclear power to energy-starved India. But just two years later, Singh’s government passed a liability law so stringent that no US company has yet committed any money. India’s persistent reluctance to push the Doha Round of World Trade Organisation talks to fruition — most recently by blocking a trade facilitation agreement at the 11th hour — has further undermined the potential for greater trade and investment.

Indeed, the true roadblocks to a more vibrant Indo-US economic relationship have been timid policies emanating from New Delhi. That has not changed under Modi, even though he swept to power promising dramatic reforms to the economy and bureaucracy. India continues to be reluctant to dismantle barriers to foreign direct investment (FDI) in sectors where the US has a strong interest, such as defence and insurance. Modi’s attempt to improve matters — raising the cap on FDI in both sectors to 49 per cent, from 26 per cent — was half-hearted. If, instead, he had raised the caps to 74 per cent or abolished them outright, he might expect to return from the US with billions of dollars in investment from just these two sectors alone. Already India is the single-largest buyer of American weapons, importing arms worth $6 billion every year. In insurance, India is one of the most under-penetrated countries in the world and the domestic market is dominated by a handful of large government-owned companies. It is ripe for foreign competition.

Other areas could be opened up for foreign investors, as well. India’s energy sector received a body blow on Wednesday when the Supreme Court cancelled more than 200 licences that had been handed out to private-sector power and steel producers to mine coal over complaints of large-scale irregularities in distribution of the coal blocks. India faces a huge coal shortfall, despite abundant reserves, because of the inefficiency of the government-owned monopoly — Coal India.

This could be a perfect opportunity to turn a setback into a strategy to attract foreign investors and transform one of India’s most vital sectors. Like many other needed reforms, though, it is going to require hard political work at home, not high-profile trips abroad.

— Washington Post

Dhiraj Nayyar is a journalist in New Delhi.