It was disquieting to hear Samantha Power, the US scholar/ambassador to the UN, saying that fresh reports of yet another poison gas attack near Hama were “unsubstantiated.” Without blushing, she added that Washington would do everything in its “power to establish what has happened and then consider possible steps in response.”

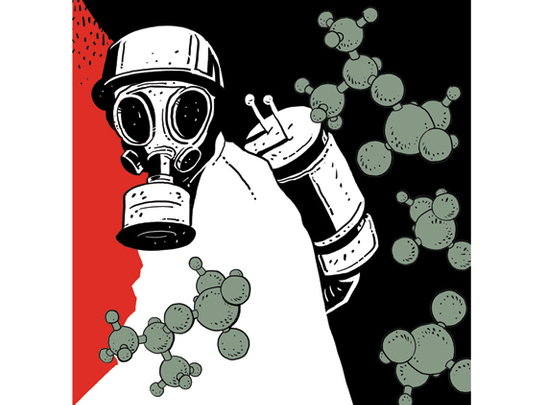

Besides being a truly embarrassing declaration, given that the August 21, 2013 Al Ghouta attacks killed several hundred Syrians and that the entire tragedy remained unanswered after President Barack Obama identified such potential use as a red line that would trigger harsh consequences, the latest use of chemical weapons was bound to be ignored too.

In fact, and while Damascus agreed to surrender its strategic weapons under a Russian-facilitated, UN-negotiated, and Western-verified agreement — though about half of the weapons were removed as of this writing according to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons — the Syrian government and opposition forces accused each other for using the banned weapons.

Then as now, Syrian State Television blamed the Jabhat Al Nusrah Front for the attacks while opposition groups quoted physicians declaring that regime planes dropped the canisters and the rockets that landed on various civilian targets, which led to suffocation and poisoning.

Then as now, independent verification was nearly impossible, although the renowned investigative reporter, Seymour M. Hersh, who first wrote about the My Lai massacres during the Vietnam War, published what must be a devastating anti-rebellion essay in the London Review of Books.

Titled, ‘The Red Line and the Rat Line’, [available on line at http://www.lrb.co.uk/v36/n08/seymour-m-hersh/the-red-line-and-the-rat-line], Hersh asserted that it was not Damascus that bombarded Al Ghouta but the rebels themselves, who were involved in a diabolical plan that relied on sarin supplied by Turkey, presumably for propaganda purposes and to accelerate a Western military assault on the Ba’ath regime.

Of course, Washington and Ankara denied Hersh’s findings that, ironically, were based on “Russian military intelligence operatives”. Why Hersh, a serious reporter who should know better, accepted the assertion that the sarin gas did not match what was presumably in the Syrian government’s stocks, was a mystery.

Naturally, intelligence operatives in all countries sometimes overplayed their hands, as was the case with ‘Curveball’ during the War for Iraq in 2003, although Hersh maintains that the Russian was “a good source” with “a record of being trustworthy.”

Amazingly, Hersh never actually met the Russian, but relied on a single unnamed former US intelligence official on whose testimony the writer relied to compose his 13 pages missive.

To be sure, it would be incorrect to assume that Russian sources cannot be honest, though the very concept of “trust-but-verify,” a slogan attributed to former President Ronald Reagan, must always apply. In this case, and for much of 2012, Moscow was desperate to prevent a Western military response against Syria and went out of its way to devise clever mechanisms to accomplish its objective. That Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov hoodwinked his American counterpart, Secretary of State John Kerry, was nearly certain as the latter acquiesced to the former’s demands.

Moreover, and even if one were to assume that opposition forces were guilty as charged, the sheer volume of sarin gas used in Al Ghouta — estimated by leading experts at nearly a tonne — could not have been easily manufactured, assembled and delivered.

Such a volume required a significant infrastructure that rebel forces did not, and do not, possess. Of course, Turkey has and continues to train Syrian rebels, though manipulating 1,000 kilos of highly unstable poison was not, and is not, as easy as implied by Hersh.

Even more problematic was the assertion that Ankara facilitated such transfers since it is not known to possess a chemical weapons programme, though it boasts the largest Nato ground forces. One cannot eliminate the possibility that the US provided the sarin via Turkey but this would fall in the domain of fiction not reality.

There were other problems with the rebel operation including sensitive concerns with delivery rockets and their launchers, which posed a serious handicap for any analysis that tied sarin gas to Turkey. Presumably, rebel forces must have acquired the Soviet-made equipment, fitted them with Western-originating sarin, and fired in near-perfect harmony, all of which necessitated tremendous coordination that, simply stated, was not there.

Again, one may be allowed to have a vivid imagination, but the more likely source of these rockets was Syria’s military that was known to train in their use even if political convenience persuaded those that wished to be easily swayed.

The Hersh essay contains a rather revealing encounter between Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey and President Barack Obama at the White House, attributed to former US National Security Advisor Tom Donilon, which affirms that Obama repeatedly cut off the Turkish intelligence chief Hakan Fidan, telling him: “We know what you’re doing with the radicals in Syria.”

Yet, how does Hersh conclude that this was related to Al Ghouta? Could this not refer to substantial Turkish assistance to Syrian rebels, especially as Ankara concluded some time ago that it could not see a future for Bashar Al Assad as President of Syria?

One is of course saddened by the deafening silence concerning the August 21 chemical weapons attack as we still do not know what happened then and might never learn the truth. If we are to wait for the Samantha Powers of this world and their “unsubstantiated” fears, we will gradually sink in unprecedented shallowness, since we are bound to also overlook what is underway in places like Hama and elsewhere.

Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is the author of Legal and Political Reforms in Saudi Arabia (London: Routledge, 2013).