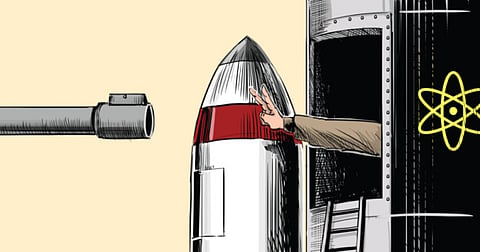

War with Iran is not an option

Ayatollah Khamenei will stop short of making nuclear weapons system a reality

“All options remain on the table,” goes the mantra. This is code for saying that the West retains the choice of using military force to stop Iran from acquiring a nuclear weapon. We will hear it repeated this week, as negotiations between Iran and the ‘P5 +1’ (the permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany) resumed in Kazakhstan yesterday. On occasions, I have used the phrase myself. However, the more I have thought about it, the more I have become convinced that it is a hindrance to negotiations, rather than a help. If Iran were to attack Israel, or, say, one of its Arab neighbours, international law is clear: The victim has the right to retaliate, but such an attack is highly improbable.

Under Article 42 of the UN Charter, the Security Council can authorise military action where there is a “threat to international peace and security”. Such resolutions were the legal basis for the actions against Iraq in 1991 and 2003 and Libya in 2011. However, there are no such Article 42 resolutions against Iran and there will not be — China and Russia will veto them. There are Security Council resolutions against Iran under Article 41, but this Article explicitly excludes measures involving the use of force. These resolutions have progressively tightened international sanctions against Iran, because of its lack of full cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

With even tougher measures imposed by the US and the European Union (EU), sanctions have severely restricted Iran’s international trade and led to the collapse of its currency and high inflation. The negotiations which restarted yesterday are the latest round of a 10-year effort by the international community to satisfy itself that Iran was not embarking on a nuclear weapons programme. This initiative was begun in 2003 by me and the then foreign ministers of France and Germany, Dominic de Villepin and Joschka Fischer, when it became clear that Iran had failed to disclose much of its activities to the IAEA, in breach of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) to which it adheres. I visited Tehran five times as foreign secretary. The Iranians are tough negotiators, more difficult to deal with because of the opacity of their governmental system. (When I complained to Kamal Kharrazi, the Iranian foreign minister, about this, he replied: “Don’t complain to me about negotiating with the Iranian government, Jack. Imagine what it’s like negotiating within the Iranian government”). They have not helped themselves by their obduracy. Resolving the current impasse will require statesmanship of a high order from both sides.

From the West, there has to be a better understanding of the Iranian psyche. Transcending their political divisions, Iranians have a strong and shared sense of national identity and a yearning to be treated with respect, after decades in which they feel (with justification) that they have been systematically humiliated, not least by the UK. “Kar Inglise” or “the hand of England” is behind whatever befalls the Iranians — is a popular Persian saying.

Few in the UK have the remotest idea of Britain’s active interference in Iran’s internal affairs from the 19th century onwards, but the Iranians can recite every detail. From an oppressive British tobacco monopoly in 1890, through truly extortionate terms for the extraction of oil by the D’Arcy petroleum company (later BP), to putting Reza Shah on the throne in the 1920s; from jointly occupying the country, with the Soviet Union, from 1941-46, organising (with the CIA) the coup to remove the elected prime minister Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953 and then propping up the increasingly brutal regime of the Shah until its collapse in 1979, Britain’s role has not been a pretty one. Think how Britons would have felt if it had been the other way round.

In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, Iranian president Mohammad Khatami reached out to the US, promising active cooperation against Al Qaida and the Taliban — and, in the initial months, delivering that. His “reward” was for Iran to be lumped in with Iraq and North Korea as part of the “axis of evil” by the then US president, George W. Bush, in January 2002 — a serious error by the US which severely weakened the moderates around Khatami and laid the ground for the hardliners who succeeded him.

If I am wrong, further isolation of Iran will follow; but will it trigger nuclear proliferation across the Middle East? Not in my view. Turkey, Egypt and Saudi Arabia “have little to gain and much to lose by embarking down such a route” is the accurate conclusion of researchers from the War Studies Department of King’s College London. In any event, a nuclear-armed Iran will certainly not be worth a war. There has been no more belligerent cheerleader for the war party against Iran than Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s Prime Minister. Netanyahu was widely expected to strengthen his position in the January elections for the Israeli parliament, but lost close to a third of his seats. The electorate seemed to take more heed of real experts such as Meir Dagan, a former head of Mossad, Israel’s external intelligence agency, and Yuval Diskin, a former chief of Shin Bet, its internal security agency. In 2011, Dagan described an Israeli attack on Iran as a “stupid idea”. More significantly, both Dagan and Diskin have questioned the utility of any strike on Iran. Diskin says there is no truth in Netanyahu’s assertion that “if Israel does act, the Iranians won’t get the bomb”. And Dagan is correct in challenging the view that if there were an Israeli attack, the Iranian regime might fall. “In case of an attack [on Iran], political pressure on the regime will disappear. If Israel will attack, there is no doubt in my mind that this will also provide them with the opportunity to go ahead and move quickly to nuclear weapons.” He added that if there was military action, the sanctions regime itself might collapse, making it easier for Iran to obtain the materiel needed to cross the nuclear threshold. As with the reality of a nuclear-armed North Korea, the international community would have to embark on containment of the threat if, militarily, Iran did go nuclear. But these hard-boiled former heads of the Israeli intelligence agencies are right. War is not an option.

Jack Straw is MP for Blackburn and was foreign secretary, 2001-2006.