US sanctions on Haqqani network?

The US pullout from Afghanistan will be qualitatively different from Iraq

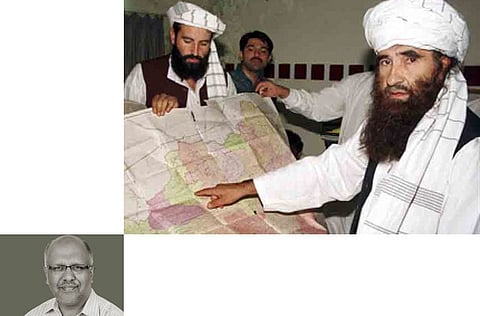

Friday’s announcement by the Barack Obama administration of declaring the Pakistan-based Haqqani network as a foreign terrorist outfit is a decision that leaves behind many unanswered questions.

In the past year, US officials have increasingly complained of fighters from this outfit being involved in attacks in Afghanistan, including one targeting the US Embassy in Kabul. If indeed the evidence is up to the mark, the US is justified in clearly retaliating. Yet, there is also an unanswered and profoundly significant question, which is: How should the US have retaliated?

With the end game in Afghanistan possibly in sight ahead of a 2014 deadline set by President Obama, the US administration clearly needs to plan its exit from the central Asian country. At stake is not just the future of Afghanistan, following one of the world’s bloodiest conflicts, but also at hand is the issue of the ability of the US to withdraw a large stock of military hardware, by some estimates worth approximately $60 billion (Dh220.68 billion). This could turn the coming withdrawal in to one of the largest military and logistical movements ever witnessed in history.

Unlike the US military pullout from Iraq, the pullout from Afghanistan will be qualitatively different in at least two ways. On the one hand, the mountainous route out of Afghanistan will take the US military through a treacherous path that has seen one invader after another travel through this punishing terrain over centuries. Compared to Iraq’s largely desert but topographically flat terrain, Afghanistan presents a potential nightmare even for the most sophisticated military planners.

On the other hand, unlike Iraq, a withdrawal from Afghanistan will leave behind a far-from-suppressed enemy. While the Iraqi resistance remains intact on the sidelines, though without popular support, the same cannot be said about Afghanistan.

The Afghan resistance of the Taliban and remnants of Al Qaida may, in fact, be more battle-hardened, having survived the onslaught of one of the world’s most technically savvy militaries. Consequently, in parts of Afghanistan, the resistance fighters have emerged as the No 1 popular force for the local population — in sharp contrast to occupying western forces working in partnership with a nominal, but controversial government of President Hamid Karzai in Kabul.

For long-term observers of Afghanistan, the challenge post-2014 will indeed be the ability of the Karzai regime to survive. This is especially true as large parts of Afghanistan have just witnessed the powerful reality of American military firepower, without a vital element of economic progress that ought to have been poured in simultaneously to gain popular approval.

Meanwhile, the now all-too-well documented large-scale corruption surrounding the top tiers of the Afghan government indeed creates an added challenge to the regime’s ability to not just survive but prosper and consolidate.

Each one of these elements either separately or taken together present a glaring nightmare for Afghanistan’s stakeholders — both from within and outside.

In this background, Washington’s withdrawal plans are at risk of getting bogged down without the assurance of a safe-passage that will allow a half-sensible pullback opportunity to US forces.

The decision to target the Haqqani network with the latest punitive measure indeed creates some important risks. To begin with, the resilience shown by the Haqqani fighters raises the question if they will seek revenge by further stepping up attacks on US-led western forces in Afghanistan. If so, this presents the US with a series of accompanying risks.

The other challenge is indeed that the targeting of the Haqqanis is the latest addition to a journey spanning the past couple of years where US officials have repeatedly accused Pakistan of backing this particular group. To a large extent, many Pakistanis are left only with a sense of disbelief, given that the US claims have seldom been backed by publicly available and verifiable evidence.

But the clubbing together of the Haqqani network with parts of Pakistan’s security establishment, notably the army-run Inter-Services Intelligence or ISI, presents fresh grounds for spoiling the US-Pakistan relationship that has already gone through periods of trials. If indeed the US is serious about taking Pakistan along in overseeing its military draw down from Afghanistan and eventually stabilise the central Asian country, there are just bigger risks from spoiling ties with Islamabad.

On the contrary, applying pressure on the Haqqanis through a mix of quiet diplomacy and quiet pressure on Pakistan may have served US interests better than the adoption of a tough public position. Having targeted the Haqqani network with the latest set of punitive measures, the Obama administration’s ability to stabilise Afghanistan only stands in danger of being reduced.

Farhan Bokhari is a Pakistan-based commentator who writes on political and economic matters.