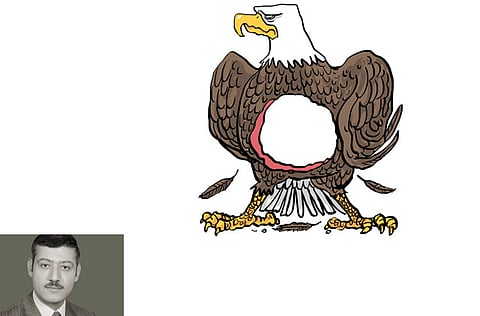

US has no stomach for world dominance

Policies on Syria and Iran highlight how much the war on terror has hurt Washington

As the US prepares to mark 11 years since the 9/11 attacks, one is tempted to look again at the ensuing shift in US foreign policy and see whether it has made America a stronger world power.

In fact, there is a clear tendency amongst analysts and policy-makers to compare 9/11 and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 in terms of events and consequences. Indeed, both are acknowledged as attacks from “out of the blue”, unprovoked, and as ‘wake up calls’ to the American people about the nature of the world in which they reside.

Two issues have been neglected in comparing the two cases, however: first, few have noted the degree of influence wielded by a dense network of think-tanks and lobbying organisations that predated both 9/11 and Pearl Harbor; and secondly, even fewer have asked whether the most profound long-term consequence of Pearl Harbor — the rise of a coherent, bi-partisan and globalist east coast foreign policy establishment that reigned at least until the end of the Vietnam War — was likely to follow 9/11. In short, was there a cross-party foreign policy consensus, focusing on pre-emption, military preparedness, and unilateralism?

The fact that 9/11 has had a profound independent impact on US foreign policy should not be discounted. Increased military budgets, development of a federal Homeland Security bureaucracy, perceived burying of the ‘Vietnam syndrome’, and the strengthening of unilateralism, are all key changes.

Yet, it was also clear that there were well-prepared political and ideological forces — specifically a neo-conservative network of lobbyists and policy advisers — waiting in the wings with a new agenda for US foreign policy, waiting to press home their own radical plans for policy shift. Their agenda refers to exporting American democracy, but not nation-building, to policing, but not ‘international social work’, and even speaks of the advantages of empire, the ‘E’ word.

A neo-conservative movement has been getting stronger since the 1970s, when Irving Kristol resurrected the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), from which former president George W. Bush borrowed at least twenty members for his administration, including John Bolton, Michael Rubin, and Richard Perle.

In the early 1990s, Edwin J. Fuelner Jr, head of the conservative Heritage Foundation, vowed to “build a new governing establishment by the end of the decade”. Later, that establishment was headed by the Project for the New American Century (PNAC) which, since its founding in 1997, had lobbied for a war of regime change and eliminating Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction.

One year before 9/11, PNAC published a radical plan (rebuilding American defences) outlining most of what became US foreign policy after 9/11: the Bush doctrine. But they were not, in September 2000, optimistic about their plans’ practicability. Indeed, they thought the only way their ideas would stand a chance of adoption was if something dramatic happened, “some cataclysmic and catalysing event — like a new Pearl Harbor”, they argued.

Back in 1941, before the real Pearl Harbor, there was an interesting parallel: a dense political-intellectual network, headed by the globalist New York Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), of anti-isolationist, liberal internationalists, who had been preparing since 1919 for US global leadership, a Pax Americana. But as war raged in Europe and the Far East, American opinion was solidly isolationist and anti-war.

CFR men, in May 1941, over six months before Pearl Harbor, felt that the only way Americans would be awakened from their well-fed, rationing-free long-vacation torpor was from “a shock [preferably a military one]”. On December 7, the shock came, and the US entered the war, promoted the ‘four freedoms’, an Anglo-American alliance, built new international institutions (such as the UN and the World Bank), and offered a New Deal to the world. The US foreign policy establishment and the Vietnam generation were born at that time.

Indeed, 9/11 created a new establishment with a detailed plan to consolidate US hegemony and strengthen America’s position in the world. It did not quite work. Eleven years after 9/11, America looks much weaker than it was on the eve of the Washington and New York attacks.

The ‘war on terror’, the invasion of Iraq and the war of attrition in Afghanistan have cost America trillions of dollars. The 2008 economic crisis has also hit America very bad. Today, the US seems to have no stomach to intervene anywhere in the world even to protect its strategic and economic interests. Syria is one example and US policy on Iran is another.

What the neo-cons hopped to gain from 9/11 turned to be mere illusions.

Dr Marwan Kabalanis the Dean of the Faculty of International Relations and Diplomacy at the University of Kalamoon, Damascus.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox