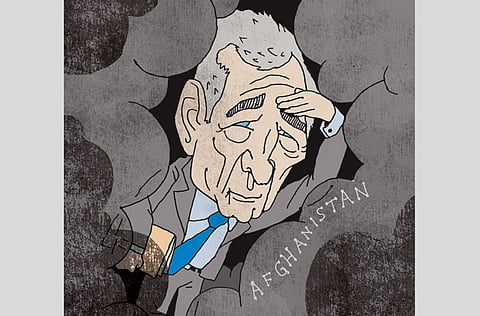

US fighting for a lost cause in Afghanistan

US has lost interest in spending lives and money to prop up Karzai

Amid partisan questioning from both sides in former senator Chuck Hagel’s confirmation hearing last week, a major opportunity was lost. Hagel’s fellow Republicans grilled the Secretary of Defence nominee on past statements about Israel and his opposition to president George W. Bush’s 2007 surge in Iraq. Democrats, defending their president’s choice, tossed him softballs.

What Hagel was not asked about in any depth was Afghanistan, where about 66,000 US troops are still risking their lives for a mission that no longer seems clear. It will be the next defence secretary’s job not only to bring most of those men and women home, ending an era of big-footprint US combat in the Muslim world, but also to help re-imagine the fight against terrorists for an era of belt-tightening.

During the nearly eight hours of Hagel’s hearing, no more than 10 minutes were spent on Afghanistan. Only three senators, all Democrats, bothered to ask about the future of the US troop commitment there. No Republican took the opportunity to express any views, whether in favour of President Barack Obama’s rapid withdrawal plan or against it.

As far as the Congress is concerned, it sounded as if the war was already over. And that is pretty much how Hagel described it as well. “We have a plan in place to transition out of Afghanistan, continue bringing our troops home and end the war,” he said. Only the war will not be over. Even when most American troops come home, as is scheduled by the end of 2014, the Afghan army and police forces will still be fighting the Taliban.

The terrorist Haqqani network, long allied with Al Qaida, will still be roaming the border with Pakistan. Local warlords will still be vying with the central government for power. And like it or not, the US will still have a big stake in the outcome.

Americans have understandably lost interest in spending more lives and money to prop up the corrupt government of Hamid Karzai. However, as Obama has noted, America still wants to make sure Al Qaida cannot regain a foothold in Afghanistan and America will still have to worry about the stability of nuclear-armed Pakistan next door. “We’re not winding down the damn war,” a former ambassador to Afghanistan, Ronald E. Neumann, growls. “We’re winding down our participation in the war. That’s extraordinarily different.”

Most of the debate in Washington has been about how quickly US troops should leave Afghanistan and how many should remain after 2014. However, those are the wrong questions. What Americans should be asking is what kind of outcome the US can realistically seek and what are the best ways to get there. Then we can discuss how many troops each of the options will require. In the short run, between now and the end of 2014, the US wants to do three things: Complete the training of 352,000 Afghan security forces; help Afghans hold a reasonably fair election to choose Karzai’s successor; and work out terms for any post-2014 US presence.

The just-departed US commander in Kabul, General John R. Allen, has pleaded publicly for as many troops as possible through 2014 to make those tasks easier. The White House has pushed back, insisting that withdrawals begin this spring. Both options are defensible. It is possible to withdraw some troops without making the rest of the mission impossible. What is not defensible is the lack of clarity in the administration’s goals and plans.

That has created a big problem for Afghans, who are adjusting their own allegiances in case the Americans suddenly disappear and the Karzai government suddenly crumbles. Without more clarity, success — even the kind of partial, ramshackle success America is now seeking — becomes more difficult to achieve. After 2014, when all US combat troops are scheduled to be out of Afghanistan, the Obama administration still foresees two missions for a “residual force”: Training and advising Afghan forces, and waging counter-terrorist operations against Al Qaida and its allies.

It is difficult to imagine that those missions can be very effective if America leaves behind only the 3,000 US troops the White House has been said to favour. (The White House has also proposed a “zero option,” but that looks mostly like a bargaining ploy in negotiations with Karzai.) Allen and Pentagon officials initially proposed keeping as many as 15,000 troops in place, but successively pared the options to a range between 3,000 and 9,000. Obama is mulling those figures and will probably make a decision in the next several weeks. However, at this point, deciding on a number is less important than deciding on a mission. America should not ask its troops — or the Afghan allies — to risk their lives for a cause that cannot be won

— Los Angeles Times

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox