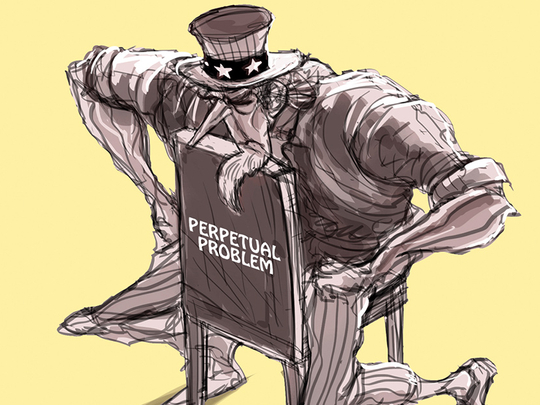

African Americans, like Palestinian Arabs, have always been viewed as a problem, or as W.E. Du Bois argued in his iconic book, The Souls of Black Folks (1903), a “perpetual problem” — that is, their very existence being a problem to be addressed, debated and commiserated with, but never solved. So how does it feel to be a problem, as opposed to having one? Well, ask the family and supporters of Michael Brown, or the family of Trayvon Martin, whose tragic deaths resonated with black folks around the nation, much in the manner that the gruesome death of 16-year-old Mohammad Abu Khudair, who was burned alive by Jewish terrorists in occupied Jerusalem, did with Palestinians and other Arabs.

In both cases, the curtain was pulled back and what we saw were not three children who were senselessly killed because they represented a problem to someone — Martin carried a bag of munchies and an iced tea, Brown was unarmed, and Abu Khudair was on his way to the mosque for morning prayer — but because their very being was a problem.

On August 28, 1963, at the March on Washington, Martin Luther King called out from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial: “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin, but by the content of their character. I have a dream.” No exhortation is more widely recognised. No American speech in the 20th century is more powerful. No words are more emblematic of the civil rights movement. And what King called for in his landmark address that day played an indirect role in the historic legislation passed soon thereafter — the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Yet, African Americans, half a century later, continue to be an underclass whose very existence as a people of colour is seen as a “perpetual problem”, despite the fact that King’s riff on the dream — of equality, equity, communal sense of reference among blacks and whites — challenged Americans to think differently about race, about the plus-minus dichotomy between the ideals of America’s founding fathers and how those ideals are practised. And, more recently, US President Barack Obama’s election had us all, as commentators, trumpeting — naively, as it turned out — the beginning of a “post-racial America”.

But that is not the way it has panned out, as events in Ferguson, Missouri, last week would attest. Consider this: As Michelle Alexander, an associate professor of Law at Ohio State University, reminds us, the struggle for civil rights is far from complete. “In 2011 alone”, she writes, “the New York City Police Department frisked more than 600,000 people, the majority of them black and brown men who were innocent of any crime or infraction, just as the sight of Trayvon Martin walking leisurely through his own neighbourhood was enough to make George Zimmerman [the security guard accused of shooting him] to call the police.”

Among those imprisoned, and later released following their sentences, she continues, most find “that their punishment is far from over. Felons are typically stripped of the very rights supposedly won in the civil rights movement, including the right to vote, the right to serve on juries and the right to be free of legal discrimination in employment, housing, access to education and public benefits ... Unable to find work or housing, [they] most wind up back in prison”.

Consider another fact well-known to researchers on the plight of African Americans in US society: Between 1960 and 1991, the population of black households headed by women increased from 24 per cent to 58 per cent. Three quarters of these women were divorced, separated or had never married. In 2008, two thirds of all black children were born to unmarried mothers and 40 per cent of all black girls became pregnant by the age of 18.

And yet! Yet, black intellectuals like Thomas Sowell, a professor of economics at Stanford University, along with black pop culture icons like Bill Cosby — whose name, because of recent revelations about his predatory sexual excesses, is now dirt, at least among whites — have urged African Americans to “get a grip” and stop seeing themselves as victims of white racism — a posture that perpetuates defeatism and apathy. Why is it, they ask, that West Indian immigrants, for example, who are black one and all, have achieved success in America whereas their African American counterparts continue to flounder?

The retort of the black underclass to its ivory tower or celebrity upper class is that American society is as racist as it has always been, the difference being one in kind — appearing as it does in a subtle guise — but not in degree.

Two decades ago, Reverend L. Francis Griffin, a longtime National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People leader, acknowledged the post-civil rights movement for what it was. “In essence”, he said, “there’s a new status quo here. There’s still a battleground, the lines of separation still exist — but the pressures are not such that there will be all-out fighting. It’s a cold war now, and I look for it to go on.” Ask the folks at Ferguson and elsewhere around the US about that.

Fawaz Turki is a journalist, lecturer and author based in Washington. He is the author of The Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile.