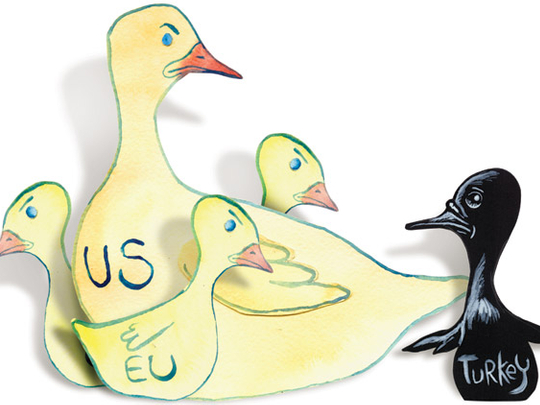

Turkey's "no" last month (a vote cast together with Brazil) to the new sanctions against Iran approved in the United Nations Security Council dramatically reveals the full extent of the country's estrangement from the West. Are we, as many commentators have argued, witnessing the consequences of the so-called "neo-Ottoman" foreign policy of Turkey's Justice and Development Party (AKP) government, which is supposedly aimed at switching camps and returning to the country's oriental Islamic roots?

I believe that these fears are exaggerated, even misplaced. And should things work out that way, this would be due more to a self-fulfilling prophecy on the West's part than to Turkey's policies.

In fact, Turkey's foreign policy, which seeks to resolve existing conflicts with and within neighbouring states, and active Turkish involvement there, is anything but in conflict with western interests. Quite the contrary. But the West (and Europe in particular) will finally have to take Turkey seriously as a partner and stop viewing it as a western client state.

Turkey is and should be a member of the G20, because, with its young, rapidly growing population it will become a very strong state economically in the 21st century. Even today, the image of Turkey as the "sick man of Europe" is no longer accurate.

When, after the UN decision, United States Secretary of Defence Robert Gates harshly criticised Europeans for having contributed to this estrangement by their behaviour towards Turkey, his undiplomatic frankness caused quite a stir in Paris and Berlin. But Gates had hit the nail on the head.

Ever since the change in government from Jacques Chirac to Nicolas Sarkozy in France and from Gerhard Schröder to Angela Merkel in Germany, Turkey has been strung along and put off by the European Union. Indeed, in the case of Cyprus, the EU wasn't even above breaking previous commitments vis-à-vis Turkey and unilaterally changing jointly-agreed rules. And, while the Europeans have formally kept to their decision to begin accession negotiations with Turkey, they have done little to advance the cause.

Only now, when the disaster in Turkish-European relations is becoming apparent, is the EU suddenly willing to open a new chapter in the negotiations (which, incidentally, clearly proves that the deadlock was politically motivated).

It can't be said often enough: Turkey is situated in a highly sensitive geopolitical location, particularly where Europe's security is concerned. The eastern Mediterranean, the Aegean, the western Balkans, the Caspian region and the southern Caucasus, Central Asia, and the Middle East are all areas where the West will achieve nothing or very little without Turkey's support. And this is true in terms not only of security policy, but also of energy policy if you're looking for alternatives to Europe's growing reliance on Russian energy supplies.

The West, and Europe in particular, can't afford to alienate Turkey, considering their interests, but objectively it is exactly this kind of estrangement that follows from European policy towards Turkey in the last few years.

Shortsighted policy

Europe's security in the 21st century will be determined to a significant degree in its neighbourhood in the southeast exactly where Turkey is crucial for Europe's security interests now and, increasingly, in the future. But, rather than binding Turkey as closely as possible to Europe and the West, European policy is driving Turkey into the arms of Russia and Iran.

This kind of policy is ironic, absurd, and shortsighted all at once. For centuries, Russia, Iran and Turkey have been regional rivals, never allies. Europe's political blindness, however, seems to override this fact.

Of course, Turkey, too, is greatly dependent on integration with the West. Should it lose this, it would drastically weaken its own position vis-à-vis its potential regional partners (and rivals), despite its ideal geopolitical location. Turkey's "no" to new sanctions against Iran in all likelihood will prove to be a significant error, unless Iran changes its nuclear policy.

Moreover, with the confrontation between Israel and Turkey strengthening radical forces in the Middle East, what is European diplomacy waiting for? The West, as well as Israel and Turkey themselves, most certainly cannot afford a permanent rupture between the two states, unless the desired outcome is for the region to continue on its path to lasting destabilisation. It is more than time for Europe to act.

Europe risks running out of time, even in its own neighbourhood, because active European foreign policy and a strong commitment on the part of the EU are sorely missed in all these countries. Or, as Mikhail Gorbachev, that great Russian statesman of the last decades of the 20th century, put it: "Life has a way of punishing those who come too late."

— Project Syndicate/Institute for Human Sciences, 2010