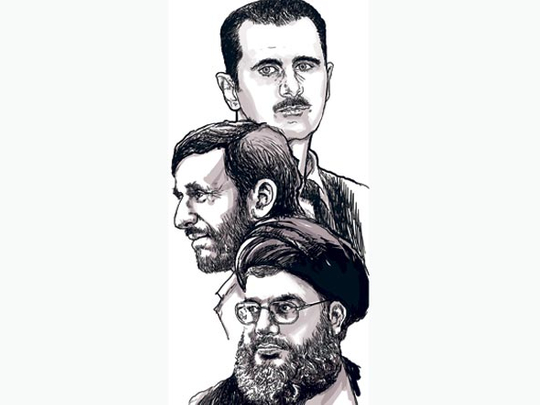

Damascus was abuzz last week with what looked like a mini-summit, bringing together Syrian President Bashar Al Assad with his Iranian counterpart Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah. This meeting, which also included a high-profile encounter between Ahmadinejad and Khalid Mesha'al of Hamas, raised eyebrows and set off alarms in the West.

It reminded western officials of high-profile summits of the 1960s, uniting Russian leaders, Jamal Abdul Nasser and Yasser Arafat against the United States. The timing of the meeting, and the words of Al Assad and Ahmadinejad, sent a strong message to Israel that it should not try to wage war next summer against either Hezbollah, Syria, Hamas or Iran or all of the above.

The ‘summit' came shortly after US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton warned Syria to move "away from the relationship with Iran" and stop supporting Hamas in Palestine, and Hezbollah in Lebanon. Ahmadinejad put it bluntly: "I say to them that the new Middle East is in the process of formation. I call on the Zionists to return to their senses and to recognise the legitimate rights of the people of the region … there will be no place for them in our region." He then added that war would lead to the "inevitable demise" of Israel.

Many are puzzled by the ‘Damascus Summit', given all the positivity surrounding Damascus and Washington. Recently, the Obama administration decided to send an ambassador to Syria to fill a post that has been vacant since 2005. Last week, William Burns, the Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs, came to Damascus to tell authorities that his country would support Syria's bid to join the World Trade Organisation. The US also decided to cross Syria off the list of countries that its citizens are warned against visiting. Daniel Benjamin, the US State Department's co-ordinator for counter-terrorism, was also in Syria with the Burns team, holding what the US embassy described as "productive and detailed" talks on counter-terrorism co-operation between Damascus and Washington, particularly in Iraq. The official statement read: "We believe Syria can play a constructive role in mitigating these and other threats in co-operation with regional states and the United States."

Some are pointing to grave Syrian disappointment with US President Barack Obama, who has been unable to advance peace talks on the Golan, and recently, changed course on a freeze on Israeli colonies as a precondition for upcoming peace talks with the Palestinians. Al Assad even said it in a recent interview: "Maybe I am optimistic about Obama, but that does not mean that I am optimistic about other institutions that play negative or paralysing roles ..." Supporters of this argument claim that while engagement with the US has led to an improvement in bilateral relations, what really matters to Syria is the Golan Heights and there has been no progress on this.

A closer look, however, reveals that Syria wants to keep all doors to Damascus open, much like it did in the 1990s, when Syria enjoyed excellent relations with the US, France, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and both Hamas and Hezbollah. Many in the West claim this is no longer possible, echoing words spoken by George W. Bush after 9/11, when he said: "Either you are with us or with the terrorists." Syria thinks otherwise, however, arguing that Syrian-Iranian relations are in the best interest of the international community, and should be seen as a blessing in disguise for the United States.

Go-between

King Abdullah Bin Abdul Aziz of Saudi Arabia shares this view, believing that Syria can indeed walk the tightrope between the so-called moderate and radical camps in the Middle East, helping influence and moderate the behaviour of Hamas, Hezbollah, and Iran. Syria has repeatedly used its influence with these players in meetings like the ones that just took place in Damascus (which perhaps were not as high profile) to get Hamas to accept the Arab Peace Initiative, for example, or to get Hezbollah more involved in the political process in Lebanon. In Iran, Syria used its influence to free 17 British sailors captured in 2007, as well as a French prisoner in the summer of 2009. Syria, after all, doesn't have a history of anti-Americanism, and has proven since 1990 that it is a credible peace partner, with whom the West can do business.

The Damascus Summit by no means indicates that engagement has come to an end between Syria and the US. Far from it; the meeting is a reminder of how helpful Syria can be in dealing with these non-state players. Nevertheless, it sends another strong message: Think twice before waging another war on Lebanon, because neither Syria nor Iran will allow it. Rather than escalate the conflict, the tripartite meeting in Damascus actually forced Israel to recalculate, thereby minimising the chances of war next summer. The leaders assembled in Damascus are clearly very confident of their abilities, and feel that neither Israel nor the US can deal with them as they have in the past. Much has changed since Obama came to power in 2009, but much remains the same, given that the Syria-Iran-Hezbollah alliance has outlived five US administrations since that of Ronald Reagan, and will likely outlive the Obama administration as well. Persuading the US to pressure Israel into seeking peace is high on Syria's agenda, and this explains the recent Damascus Summit.

Sami Moubayed is editor-in-chief of Forward Magazine.