Most American presidents’ reputations improve after they leave office. In the warm light of history, once-derided chief executives seem to gain retroactive stature.

The most vivid example is Harry Truman, who left the White House during the Korean War with the lowest job approval ever recorded by Gallup — 22 per cent! — but has since steadily risen in the eyes of historians and the general public. The same is true of Bill Clinton, who left office under a hail of ethics questions but is now considered a bona fide Wise Man by Democrats and even some Republicans. It’s even true of Lyndon B. Johnson, whose achievements on civil rights have almost balanced out the agonies of the Vietnam War.

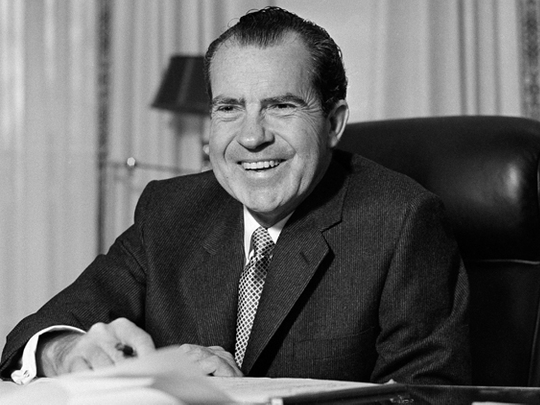

But not Richard M. Nixon. Nixon, who resigned 40 years ago Saturday, has somehow managed the opposite feat: A generation after his departure, he looks even worse.

“Emerson said that in time, every scoundrel becomes a hero, but that hasn’t been true with Nixon,” presidential historian Robert Dallek told me last week.

Whenever pollsters ask Americans who our worst presidents have been, Nixon is high in the running. Yes, a poll last month found Barack Obama in first place for “worst president” and George W. Bush in second, but that reflected partisan reflexes, not historical judgment. Nixon still finished third, 40 years after flying home to San Clemente — and unlike Obama and Bush, his detractors come from both parties.

What’s the secret of Nixon’s unpopularity? He mostly has himself to thank. Not only did he order Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) investigations of his political adversaries, he rashly recorded almost every word he uttered. Historians are still feasting on the Nixon tapes, which show RN (as aides called him) to be even nastier and more obsessive than his opponents believed at the time.

There are the offhand racial and ethnic slurs: “Most Jews are disloyal.... The Irish can’t drink.... The Italians, of course, just don’t have their heads screwed on tight.” Mexican Americans “steal; they’re dishonest ... [but] they do have a concept of family life. They don’t live like a bunch of dogs, which the Negroes do live like.”

But even before all that bigotry surfaced, the tapes helped convict Nixon (in the court of public opinion) of the crimes of Watergate in 1974. Successive releases have only made his culpability clearer.

“The tapes show how ugly he could be, his paranoia,” Dallek said. “It was a classic case of psychological projection: I manipulate and scheme, and everyone else must be like me.”

Here’s another excerpt from 1971, in which Nixon rages about the “mythology” that grew around his assassinated predecessor, John F. Kennedy:

“We have created no mythology,” Nixon complained. “For Christ’s sakes, can’t we get across the courage more? Courage, boldness, guts! Goddamn it! That is the thing.... Don’t you agree, Henry?” “Totally,” replied Henry A. Kissinger, his national security advisor. “Complexity and guts.”

But it’s not only the tapes.

Aside from Watergate — a gigantic “aside” — Nixon’s presidency wasn’t a failure. In domestic policy, he established the Environmental Protection Agency and administered the court-ordered desegregation of Southern schools. In foreign policy, he pursued nuclear arms control with the Soviet Union and, of course, opened a strategic relationship with communist China.

But Nixon’s legacy has been orphaned, even — especially — in his own Republican Party. In the wake of Nixon’s fall, GOP conservatives repudiated his big-government solutions and made Reagan, a small-government man, their champion and ideal.

Even in foreign affairs, where Nixon’s accomplishments were undeniable, his cold-blooded realism fell into disrepute. The tapes haven’t helped on that count either. Here’s Nixon as he orders new air strikes against North Vietnam in 1972: “Punish them. And, incidentally, I wouldn’t be worried about a little slop-over.... Knock off a few villages and hamlets.”

Nixon’s most durable legacy, alas, may be the heightened cynicism and partisanship that has infected both parties ever since. “Nixon’s betrayal of the public trust fuelled a general cynicism and antagonism that people have felt toward presidents and the federal government ever since,” Dallek told me.

And, surely without intending to, Nixon helped make the threat of impeachment a recurring feature of congressional debate. In 1998, Clinton was impeached (and acquitted) over his attempt to cover up his affair with intern Monica Lewinsky. And legislators have called for the impeachment at various times of both presidents George W. Bush and Obama.

The difference, of course, is that Nixon’s impeachment was a bipartisan affair; it was Republicans who pushed him out of office, not Democrats. RN was ready to hang on and fight until Republican leaders in Congress told him that his base of support, even in their once-loyal ranks, was gone.

That’s why it’s worth looking back at Nixon’s fall from this vantage point, 40 years later. In honour of the anniversary, a crop of new books has appeared, including The Nixon Tapes, an excellent collection edited by Douglas Brinkley and Luke Nichter, and The Nixon Defense, a day-by-day chronicle of Watergate by former White House counsel John W. Dean.

The volumes are enormous and depressing — but still worth reading. Anyone old enough to remember the lugubrious cadences of Nixon’s speech will find them strangely addictive. And anyone born after 1960 should at least take a look — to find out what real abuse of power and a real constitutional crisis look like.

— Los Angeles Times