The road ahead for Libya: The making of a failed state

Crumbling institutions, militias with increasing sway point to an uncertain future

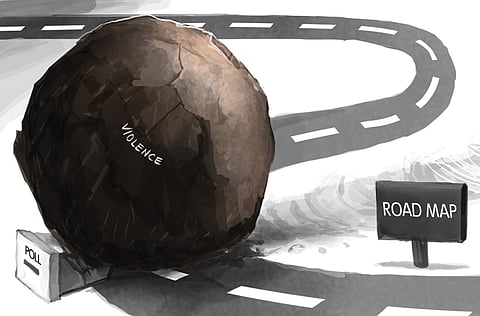

A neatly packaged TV report was aired on the BBC on February 20, showing cheerful Libyans lining up to elect a 60-member assembly that will be entrusted to draft the country’s constitution. But the reality on the ground shows that such an endeavour is doomed to fail. Libya’s state institutions are crumbling and violence is spreading. Another vote in an unpopular election will change little on the ground.

Even though there was much violence reported, a massive boycott of the elections took place to the extent where some Arab media completely ignored the vote. The BBC reported that in the eastern town of Derna, five polling stations were bombed.

The fight in Libya is not one pertaining to mere technical or legal differences over dates of voting, the mandate of the interim government or the General National Congress (GNC). Undoubtedly, the power struggle runs deep and is threatening the very territorial cohesion of the country.

What makes the Libyan case particularly complex is that power struggles often take place within the branches of political hierarchy, the military, or between both. But Libya’s national military is too weak and irrelevant to be taken seriously. It is the militias, multiplying rapidly over the expanse of a once unified country that significantly complicated the scene. Of course, the militias are growing partly because many segments of Libyan society have no faith in the government or the GNC, and especially of the dubious process that led to their formation.

Libyans are growing disenchanted by the current status quo. But considering that there are no truly functioning state institutions through which the populace can impose its will, militias are growing and becoming more violent. Since the February 17, 2011 uprising, and the Nato war that followed, Libya was broken up around regional and tribal loyalties and, in some communities, ethnicity.

Reporting for the Libya Herald on February 18, Ahmad Elumami wrote of “confusion” at the GNC headquarters “after it was announced on TV that Zintan’s Qaqaa and Sawaiq brigades had issued an ultimatum to its members to resign by 10pm or be arrested.”

Indeed, this is a confusing situation. Some of the Libyan militias imposed their own rules within areas they govern where they operate their own prisons, and, as reported by various human rights groups, torture their opponents at will.

But the latest events are linked to a chain of events that has defined Libya’s chaos for many months. On February 14, 92 prisoners escaped from their prison in the Libyan town of Zliten. Nineteen of them were eventually recaptured, two of whom were wounded in clashes with the guards. It was just another daily episode highlighting the utter chaos which has engulfed Libya since the overthrow of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi in 2011.

On that day, February 14, Major-General Khalifa Hifter announced a coup in Libya.

“The national command of the Libyan Army is declaring a movement for a new road map” [to rescue the country], Hifter declared through a video post. Oddly enough, little followed by way of a major military deployment in any part of the country. Libya’s Prime Minister Ali Zeidan described the attempted coup as “ridiculous”.

Hifter’s failed coup attempt generated nothing but more attention to Libya’s fractious reality following Nato’s war that was branded a humanitarian intervention.

“Libya is stable,” Zeidan told Reuters. “[The parliament] is doing its work, and so is the government.”

But Zedian’s statements are a contradiction to reality. In fact, the prime minister was himself kidnapped by one militia last October. Hours later, he was released by another militia. Although both, like the rest of the militias, are operating outside government confines, many are directly or loosely affiliated with government officials. In Libya, to have sway over a militia is to have influence over local, regional or national agendas. Unfortunate as it may be, this is the ‘new Libya.’

Libya’s bedlam however is not a result of some intrinsic tendency to shun order. Libyans, like people all over the world, seek security and stability in their lives. However, other parties, Arab and western, are keen to ensure that the ‘new Libya’ is consistent with their own interests, even if such interests are obtained at the expense of millions of Libyans.

CIA dealings

The New York Times’ David Kirkpatrick reported on the development from Cairo. In his report, he drew similarities between Libya and Egypt; in the case of Egypt, the military succeeded in consolidating its powers starting on July 3, whereas in Libya a strong military institution never existed in the first place. In order for Hifter to stage a coup, he would need to rely on more than a weak and splintered military.

Nonetheless, it is quite interesting that the New York Times chose to place Hifter’s “ridiculous” coup within an Egyptian context, while there is a more immediate and far more relevant context at hand, one of which the newspaper and its veteran correspondents should know very well. It is no secret that Hifter has had strong backing from the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) for nearly three decades.

The man has been branded and rebranded throughout his colourful history more times than one can summarise in a single article. He fought as an officer in the Chadian-Libyan conflict, and was captured alongside his entire unit of 600 men. During his time in prison, Chad experienced a regime change (both regimes were backed by French and US intelligence) and Hifter and his men were released per US request to another African country. While some chose to return home, others knew well what would await them in Libya, for reasons explained by the Times on May 17, 1991.

“For two years, United States officials have been shopping around for a home for about 350 Libyan soldiers who cannot return to their country because American intelligence officials had mobilised them into a commando force to overthrow Colonel Muammar Al Gaddafi,” the New York Times reported. “Now, the Administration has given up trying to find another country that will accept the Libyans and has decided to bring them to the United States.”

Writing in the Business Insider, Russ Baker traced much of Hifter’s activities since his split from Gaddafi and adoption by the CIA.

“A Congressional Research Service report of December 1996 named Hifter as the head of the NFSL’s military wing, the Libyan National Army. After he joined the exile group, the CRS report added, Hifter began ‘preparing an army to march on Libya’. The NFSL, the CSR said, is in exile ‘with many of its members in the United States.”

The Libyan plot is thickening. Stability remains elusive, thus the chances for outside powers eager to impose their own version of ‘order’ increase. What future awaits Libya is hard to predict, but with western and Arab intelligence fingerprints found all over the Libyan bedlam, the future is uninviting.

— Ramzy Baroud is an internationally-syndicated columnist, a media consultant and the editor of PalestineChronicle.com. His latest book is ‘My Father Was a Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story’ (Pluto Press, London).

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox