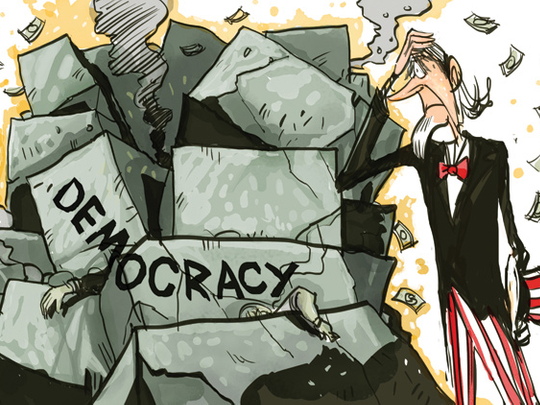

Except Tunisia, in most Arab countries, where a popular uprising has taken place, chaos and instability have prevailed. Scholars and analysts, who never believed that the Arab world could ever embrace democracy as a political and economic system, took advantage of the post-revolution difficult conditions in Libya, Yemen and Syria to influence the public debate in the US about the Middle East. “The fact that a state is despotic does not necessarily make it immoral. That is the essential fact of the Middle East that those intent on enforcing democracy abroad forget,” Robert Kaplan, a distinguished US writer, argued in an article published in the Washington Post.

More than a decade ago, such voices were eclipsed by the shock of 9/11. At the time, the real threat for America seemed to be coming from undemocratic regimes and ‘failed states’ in the Middle East. The rationale behind this argument was that there are ‘failed’, ‘rogue’ and ‘weak’ states in the world that are, in varying ways, brutalising and killing their own people, disrupting regional stability, developing weapons of mass destruction, engaging in acts of terror or are linked with violent anti-western terrorist organisations. In such cases, it is the moral duty of democratic states to intervene in a variety of ways, including militarily, and even preemptively, to ensure that humanitarian crises are brought to an end, that good government is restored or implanted and that order reigns. Policymakers could not agree more. “In a world where evil is still very real, democratic principles must be backed with power in all its forms: Political and economic, cultural and moral, and yes, sometimes military”, former secretary of state Condoleezza Rice suggested once. Iraq was the first step in a long process to implement this strategy: Overthrow Arab autocrats and replace them with democratically elected governments.

The failure in Iraq to promote democracy, or at least restore order and stability after the removal of Saddam Hussain’s regime, relegated this argument to the dustbin of history.

The opportunity presented by the uprisings in the Arab world to advance the cause of democracy did not hence create much interest in Washington. Compared to the costly intervention in Iraq, for example, the US was absolutely reluctant to pay the price to further the cause of democracy in various parts of the Arab world.

Pressure for democracy

In fact, US President Barack Obama has not been particularly interested in the kind of rhetoric that featured prominently under his predecessor and focused on democratic change in the Middle East instead. This trend reflected a return to ‘pragmatism’ in US foreign policy. So-called traditional realists in and around the Obama administration argued that pressure for democracy will present the US with a number of immediate dangers and few clear advantages. The likelihood of the Middle East producing fully democratic regimes in the next 10-15 years is remote; it enjoys none of the recognised prerequisites for sustaining democracy: its elites are not committed to democracy; its population is not homogeneous; and its national institutions are extremely weak to survive the process of transition to democracy.

Furthermore, the transition to democracy would almost certainly lead to the disintegration of state institutions, such as the army and police, and Arab countries would slip into chaos and inter-confessional violence. Worse still for this school of thought was that the likely alternative to the existing Arab regimes were Islamic governments. When the Obama administration came to power in 2008, developments on the grounds in Iraq and Afghanistan seemed to be approving this argument. Obama therefore dumped the democracy promotion thesis and decided to focus instead on stability.

In Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen, Syria and even in Libya, Washington seemed to have been quite content with the status quo and was forced to adjust its policy only when it became absolutely clear that change was irreversible. Indeed, the Arab Spring seemed to have shaken the very foundations of the pro-stability champions, but that was only for a while. As the Arab Spring turned to be more of a winter, they gained momentum.

The events of the past three years have not only affected western policies in the Middle East; in the Arab world too people have become more wary about the prospect of change. Change turned to be much more difficult, bloodier and more costly than anybody had initially anticipated. After all, the pro-stability western school of thought may have been absolutely right about its assessment of the fragility of the Arab state and the fragmentation of Arab societies. Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Libya have all shown how difficult change may turn out to be. Yet, high cost, history tells, has never prevented change from happening anyway.

Dr Marwan Kabalan is a Syrian academic and writer.

See also A2 Page 5

_resources1_16a45059ca3_small.jpg)