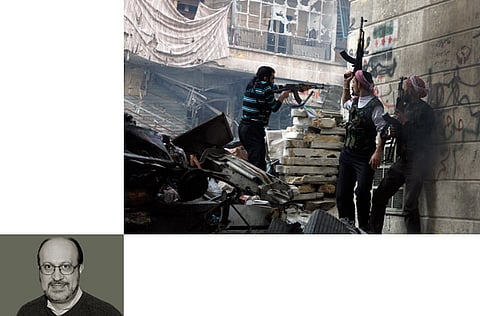

The last word on Syria is yet to be said

No simple settlement can now be imposed through a ceasefire in Syria

Lakhdar Brahimi, the joint UN-Arab League envoy for Syria, warned that as many as 100,000 people could die in 2013 without a way to end the country’s ongoing civil war. He told reporters in Cairo that if the international political crisis continued, Syria would face “Somalisation, which means warlords, and the Syrian people will be persecuted by those who control their fate.” He even presaged waves of fresh refugees, which would destabilise neighbouring countries, but especially Lebanon and Jordan, since panic in Damascus would witness a million people leaving the capital for Beirut and Amman. Lebanon and Jordan, which have already accommodated about 300,000 Syrian refugees each, could literally break, Brahimi opined. “If the only alternative is really hell or a political process, then we have got, all of us, to work ceaselessly for a political process,” he affirmed.

Few will disagree that a peaceful settlement will be preferable to war and misery, though Moscow’s adamant support to President Bashar Al Assad, and the latter’s refusal to step down as a precondition to talks, were equally critical contributors to the prolongation of the conflict. Still, after nearly 50,000 dead (most of whom were mowed down in 2012), countless missing, and millions of refugees, few Syrians were inclined to concede.

What began as pro-democracy protests morphed into an open civil war and it was critical to understand that no simple settlement can now be imposed through a ceasefire, or through the formation of a transitional government. To his credit, Brahimi has not spelled out the conditions under which free or even fair elections can be held, or whether opposition parties will be allowed to run. It is worth recalling that a referendum was held on February 26 to approve a new constitution, followed by a parliamentary election to the Syrian People’s Congress on May 7, 2012, when opposition parties barely won five of 250 seats. Last May, 245 parliament seats were claimed by Baath minions, which only lost a single post. Needless to say that in a presidential election, where at least two candidates will face each other, one expected something other than 99.99 per cent in favour of the winning candidate, assuming that Syrians will be allowed to cast their votes freely.

Still, Brahimi wants the war to end and, by his own admission, “the situation in Syria is bad and … deteriorating,” with worse still to come. “The choice is between a political solution or of full collapse of the Syrian state,” he predicted, which begged the question: Was Syria a failed state or the regime a disastrous arrangement?

To be sure, Brahimi, along with everyone else, knows quite well that the Baath regime is a spent ideological force, though all appear to debate what will happen next. No one knows, of course, how the end will come but one thing is certain: Syria will neither be divided nor be ruled by sectarianism. In fact, and by all objective accounts, the war is not going well for Damascus and conditions for Bashar Al Assad as well as his inner circle continue to deteriorate. Some accounts suggest that the president is “isolated and fearful,” not sleeping in the same bed two nights in a row. His military machine, which failed to liberate a single inch of the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights and that practised with ferocity on the Lebanese Army, Palestinian guerillas, various militias as well as its Christian and Muslim citizens throughout the 1976-2005 period, that mighty machine probably lost its operational capacity to function as an organised and disciplined military. Yet, despite ferocious attacks on the weak, Syrians did not engage in sectarian warfare.

Unlike Muammar Gaddafi, the paragon of a successful Arab leader who once counselled every Lebanese Christian to convert to Islam, no Syrian — Islamist or otherwise — has called for such a measure. On the contrary, only supporters of the Al Assad government underlined inevitable sectarian tensions and made predictions that what was bound to happen on the Syrian streets would make the post-Gaddafi Libya or post-Saddam Hussain Iraq look like picnics. Simply stated, and while added violence may be inevitable over the short term, Syrian society was and is too secularised to tolerate extremism, though Muath Al Khateeb and his interim government will have to be super vigilant. Few should anticipate outright religious clashes against minorities, especially Alawites, even if the latter’s leaders committed egregious errors. Indeed, Alawite clerics have been secretly meeting with their Sunni counterparts precisely to avoid such bloodshed, and while isolated incidents were likely to occur, those salivating outright religious pogroms are likely to be disappointed.

Likewise, Syria was poised to abandon its three-decades old strategic error, which saw Damascus align itself with Tehran. Given the overall destruction that Syria experienced during the past two years, massive foreign assistance will be required to begin the reconstruction period and chances were excellent that Arab Gulf States will come to play exceptional roles in addressing such needs. Beyond financial aid, however, Saudi influence in particular will be far greater than most assume, which would want to savour its putative victory over non-Arab actors meddling in what ought not to be their writ.

Finally, and as Turkey and Iran continue to compete over the Arab world, the latter will most likely distance itself from both, assuming responsibility for its own destiny, no matter how convoluted. In fact, carefully monitored arms shipments, with Turkey forcing the landing of several flights into Diyarbakir and elsewhere, along with the presence of advisers, trainers and snipers — some of whom were arrested while others were killed — all documented the reality from which the next Syrian leaders would surely want to extricate themselves and fast.

Consequently, and while the Baath regime may be a failed system, a new Syrian Phoenix is posed to rise just like its Lebanese counterpart did in 2005, ironically from the throngs of its corroded neighbour’s tentacles. Damascus will, once again, embark upon a nation-building train that will usher in a fair democratising authority even if the voyage may spread over a few generations. The Baath regime may have failed, but the country has not and Syria will survive no matter how many envoys predict doom and gloom.

Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is the author of Legal and Political Reforms in Saudi Arabia.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox