The Damascus conundrum

Al Assad faces the prospect of a military coup or civil war as growing army defections weaken him

True to its weathered temperament, the lone surviving Baath regime finally accepted a rescue plan put together by the moribund and largely irrelevant Arab League to stop the bloodshed that paralysed Syria for the past seven months. Astonishingly, few expect Damascus to abide by the League's terms it voluntarily ascribed to, with a growing fear that Syria may sink into an outright civil war.

Will Damascus fall into the political trap, which seems to be under final assembly, or will military leaders save the country by organising a coup d'état?

Like disorders elsewhere, the Syrian crisis is a genuine internal uprising, devoid of foreign instigation. Opposition forces here and there may have received international support, but all such assistance came after the fact and, unlike Libya, Nato military intervention is not currently foreseen.

Yet, by accepting the League's latest conditions, President Bashar Al Assad put to lie his own rhetoric that identified western powers, led by the US and France, as being the conspirators that wanted a regime change in Damascus. To be sure, and with the exception of a few challenged governments that believed in Syria's oratorical skills, the international community favoured such an outcome.

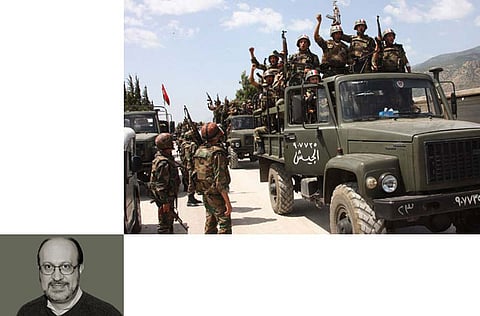

Nevertheless, by accepting the League's plan to stop the killings and withdraw military vehicles from its streets, Damascus recognised that the bulk of its army was used to control the hapless and largely unarmed Syrian population.

Truth be told, no demonstrators were clamouring for the deployment of foreign troops, even if several called for international protection. In fact, the bulk of the fighting was among Syrian troops, with daily defections to what is quickly becoming the ‘Free Syrian Army'.

Besides, by releasing several hundred prisoners, Damascus acknowledged that too many citizens were arrested during the past few months, which is a clear indication that unusual activities were under way ever since the first uprisings in Daraa.

Rights abuses

Ironically, the League's plan that called for the release of detainees was an exceptionally honest illustration of what ailed Syria, since a loyal and happy population would not, under normal circumstances, be denied its basic rights or carted off en masse for ‘investigations' that lasted weeks if not months.

Of course, the regime insisted that "armed terrorist gangs" were responsible for the havoc in the country, and those arrested to date were guilty of such wanton behaviour. Regrettably for Damascus, no evidence emerged to avow such claims, though hundreds of videos displaying atrocities filled the internet.

At this late hour, the Syrian regime is faced with a growing conundrum, which threatens its very survival as a political organisation: how to accept League reconciliation efforts without making necessary concessions to opposition circles. Indeed, this puzzle preoccupied Damascus because the regime was not ready to kowtow to the Syrian National Council led by Burhan Ghalioun, nor to accept League demands to withdraw troops from major towns and cities.

No one, not even the affable Qatari prime minister who is presiding over League negotiations, believes that this is about to occur. Rather, the general consensus is that Al Assad wants to gain time, hoping that demonstrators would eventually tire and surrender. Except that this was not about to happen for two simple reasons: demonstrators were no longer afraid and, more important, if Damascus could clear the streets, it would have done so much sooner.

At this moment in time, no one can put a stop to protests, nor can anyone predict when the ugly face of sectarianism will emerge in Syria. Equally important, and this is not lost on the regime, every passing day will strengthen opposition forces as the economic strangulation of Syria tightens, and as Arab and world public opinion turn against the Baath government.

Lest one believe the state's optimistic outlook, conditions on the ground are getting worse, as a civil war looms over the horizon. Indeed, credible reports out of Hama, Homs, Dayr Al Zor and elsewhere attest that killings on the basis of ID cards between Sunnis and Alawites for example, are not isolated.

To avoid an outright civil war, which Al Assad can "manage" for months, the time may not be long before continued army defections raise the stakes for senior officers. Today, defections are much higher than the regime recognises, which is truly the source of weapons seen on Syrian streets. No one should doubt that an increasing number of Syrian soldiers are refusing to fire on demonstrators and, by taking such stands, becoming primary targets for troops loyal to the Baath party.

Under the circumstances, and as Damascus gradually loses control over security conditions, a military coup can no longer be dismissed as an impossibility. In fact, and unlike developments elsewhere in the Arab world, this might be a quick way out that will put an end to the ongoing killings. Over time, however, and to avoid the unstable model of Syrian coup d'états between 1949 and 1970, it was critical for the military to accept civilian rule.

Can Syria emerge from this crisis without a full-blown civil war? Will military officers take matters into their own hands? How will the League react to a coup and will a Syrian solution help the League approve an outcome that was not made at the United Nations Security Council?

Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is a commentator and author of several books on Gulf affairs.