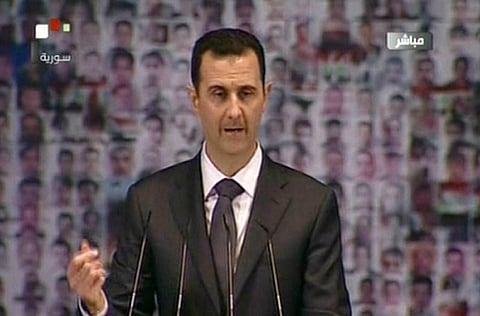

Syria’s lurking danger

Al Assad may be testing US reaction, but Syria already has a humanitarian crisis

Does it matter whether the Bashar Al Assad regime unleashed toxic chemicals on a bread queue of Syrian civilians in Homs on December 23, 2012, and if it did, what they were?

A January 15 scoop by Foreign Policy’s Josh Rogin, who was leaked reports of a US State Department cable detailing an investigation undertaken by officials at the US Consulate in Istanbul, quoted an unnamed official: “We can’t say for sure, but Syrian contacts made a compelling case that Agent 15 was used in Homs on December 23.”

In response, Wired Magazine questions whether the alleged chemical, a hallucinogen known as Agent 15 or BZ, would have produced the symptoms reported by Syrian observers and purportedly documented in videos. And the Barack Obama administration issued this careful response to Rogin’s reporting, saying the reporting of the incident had “not been consistent with what we believe to be true about the Syrian chemical weapons programme”.

However, let us back up. Rogin spoke to Syrian doctors who said the incident on December 23, whatever its cause, killed five and harmed more than 100. One hundred people a day are dying in Syria now; the UN says 60,000 have died since the “Syrian Spring” began as nonviolent protests against Al Assad 21 months ago.

If it is humanitarian outrage that you want, pay attention to the attack on Aleppo’s university last Tuesday, which killed more than 80 students and refugees; or the conditions in refugee camps, where tens of thousands are living through winter without warm clothes or shelter, while a UN appeal for humanitarian assistance is only 25 per cent funded.

From a humanitarian perspective, the question of chemical weapons is a profound distraction. Either suffering of this magnitude is a regional and global matter of consequence, or it is not. And, equally painful, either there is a workable plan to end it from outside, through negotiations, force or some combination of the two, or there is not.

No. Ultimately, this mini-story tells us more about politicians in the West than about Al Assad’s regime and the fight to determine what comes after it.

The Obama administration made chemical weapons’ use a “redline”. Why? Because of the weapons’ potential to kill thousands a day, not hundreds, but also because of the desire to maintain a taboo, however weak, against the use of such weapons anywhere, in order to protect US interests, forces and citizens from them.

If Rogin’s report is correct, the Al Assad regime chose to use a chemical agent that is controlled under the Chemical Weapons Convention, but that is not one of the more lethal agents available to it. This suggests that Al Assad may be testing and taunting Washington, but also that the White House threat has deterred him, so far, from using the Sarin and other agents in his arsenal.

However, whether it is correct or not, the back-and-forth lays bare a set of efforts to move US policy based on that redline. Syrian opposition figures clearly worked hard to tell American diplomats and Rogin, that chemical weapons had been used. What is perhaps even more interesting, from Washington’s perspective, is that a State Department that has been very nearly watertight under Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, suddenly sees anonymous officials briefing reporters on the content of classified cables. There are, then, those inside government who want to use that pledge of a “redline” to press for more aggressive action as well.

Al Assad’s willingness to flirt with the use of banned chemical weapons should be a matter of great concern for his last protector, Russia, and its UN security council enabler, China. Both countries face violent extremist movements at home; they now face a choice between legitimising the use of weapons of mass destruction or accepting that a regime that does so cannot be legitimate and thence becoming constructive partners toward a post-Al Assad order.

However, chemical weapons, which are relatively easily dispersed, and of which Syria has massive quantities, are in some ways a perfect symbol for the fluid civil conflict that is consuming the country. As chairman of the Joint Chiefs-of-Staff, Martin Dempsey, said last week: “The act of preventing the use of chemical weapons would be almost unachievable.”

The problem remains recreating an environment in which bombing university campuses, using chemical weapons and inciting inter-ethnic atrocities are equally unthinkable.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Heather Hurlburt is executive director of the National Security Network in Washington DC.