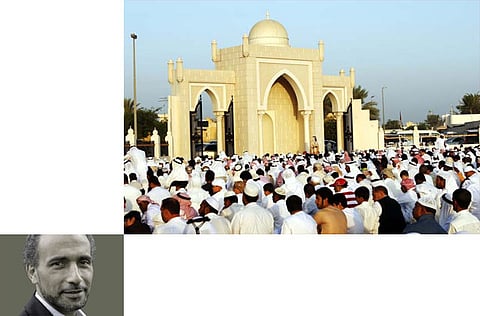

Superstition has poisoned the contemporary Muslim conscience

Islam need the kind of guidance that respects all beings

What more can we say about the malaise of the Muslims, their crises and their shortcomings, their inability to meet the challenges of the day? Islam today is in disrepute; Muslims are under attack daily for the violence carried out in their name, for the discrimination against women and “non-Muslims” — that some claim to justify in their teachings and preachings.

From within, Muslims themselves are the sharpest critics of their deficiencies and failings: They complain about their scholars, their leaders, their internal divisions, of the sad state of Muslim majority societies where education is a disaster, social justice a mirage and political systems are dens of corruption.

Both from outside and within, the verdict is inescapable: The crisis is deep and doubts have undermined confidence and conscience. It has happened in silence or is accompanied by complaints, fears, sufferings, frustrations and tears. How can we escape the prison of pretense, of posturing, of constant whining or sterile criticism? Is there a way for us to become constructively self-critical, to gain confidence and freedom? What path will lead us to peace?

We begin with a paradox. Only in the crucible of self-mastery can freedom be smelted. Far from how others see us, far from our constant complaining, we all have a deep need for silence and introspection: The silence of our conscience. We need to listen to our hearts, to recognise our needs. Islam — like all spiritual traditions — teaches that we can never fully realise ourselves, never attain freedom by acting against others, or in relation to the judgements of others.

Knowledge of God, the Quran reminds us, lies “between man and his heart”: God invites us to know ourselves, to rely upon our conscience, to seek responsibility. But above all, God summons us to understand our faith, our practice as believers and ourselves. The Unique calls upon humans to become beings of conscience, to take full command of their own selves and to become — overcoming all obstacles — forces for good, for the peace and well-being of human beings.

We must begin by avoiding the obsession of formalism, of claims that strength of faith depends on enforcing prohibitions. Strength of faith lies instead in understanding the ultimate goal of the journey. To believe is to understand ... to understand that our reason is sometimes unable to understand.

Above all, it is to grasp the primary meaning of “Tawhid,” the oneness of the divine: To recognise the presence of the divine within us, to observe His signs in the universe and to learn to thank those we love — the love of Nature, as it is spread before us, for the beauty bestowed upon us. Faith begins with thanks, as Luqman the Wise taught his son; but we cannot be fully thankful unless we understand exactly what has been given to us. Our age has taught us to be quick to complain about what we lack, yet how rapidly we forget the richness that the Unique, and that life itself, have bestowed upon us?

And here lies another paradox: The heart knows that its richness depends upon acknowledging its failings and its poverty. Far from judging others, far from dogmatism, Muslims today must keep silent, must examine themselves. Such is their journey towards the richness of the heart, of conscience and of peace. The greatest challenge of our era is to deepen our understanding and our love. Spirituality is the light of conscience and it lends meaning to our lives, it illuminates our path.

At stake is nothing less than freedom. The superstition of the masses and the elitist attitudes of scholarly circles (Ulemas) or mystics (Sufis) have poisoned contemporary Muslim conscience. When the teaching of principles and rituals focuses on limits and prohibitions, we see more and more ordinary Muslims giving their hearts to dead “saints” while educated young people turn to narrow-minded, scholarly elitists or to mystical groups — convinced that they alone “understand” while the “masses” follow suit blindly. Both attitudes are symptoms of today’s crisis.

Islam and the Muslims need the kind of guidance that respects all beings, women as well as men, poor as well as rich, blacks as well as whites, Asians as well as others. Muslims are in need of guidance which — because it respects each individual conscience, intelligence and heart — takes full account of social and historical realities and of cultural memories. Full respect of fellow human beings means not to descend into superstition, not to idealise “saints” and scholars and not to be consumed by blind emotion that can transform dynamism into populism (whose religious variant is the most dangerous of all). The humility of educated citizens and scholars consists of studying — and serving. The challenges they face — whether Muslim or not — are those of ego, wealth and power.

It is time to stop lamenting if life fails to ease our sufferings and our tears. Muslims must reconcile themselves with the full force of this message. They must rediscover the Divine One in intimate dialogue, and then, in confidence, find themselves. They must become responsible: Such is the first freedom. They must never lose hope: Such is the ultimate message of Islam.

To be, to know one’s self, to be thankful and to serve the deep belief that peace lies in the intention and the meaning of all we do and not in the visibility of the result or the sound of applause. A philosopher observed: “What does not kill you makes you stronger” ... life, which, by definition, does not definitely kill us, must be the way that strengthens us spiritually. Time, confidence and silence will be required; we must learn to care for ourselves. Islam needs all Muslims to understand its teachings, to attempt to live by them and bear witness before humanity and Nature and to believe in the simple, luminous and yet demanding message: If you believe you seek; when you seek you love; if you love you serve; when you serve, you pray.

Self-reconciliation can only come about through the mediation of those around us, with their respect and in their service. Like the signs of the universe that remind us of the signs of our deepest intimacy, like the order of the cosmos that reflects peace of mind, we must learn, understand and step outside ourselves. To love and to serve means to step outside ourselves; to step outside ourselves holds the promise of self-reconciliation. A final paradox and such a beautiful piece of truth.

Tariq Ramadan is professor of Contemporary Islamic Studies in the Faculty of Oriental Studies at Oxford University and a visiting professor at the Faculty of Islamic Studies in Qatar. He is the author of Islam and the Arab Awakening.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox