The day was August 7, 1990. It was a quiet and hushed afternoon in Baghdad when my next door neighbour rang our door bell. Umm Tawfiq's house was adjacent to ours in the capital's Al Waziriya district. The previous night, she and her family had visited our home. Along with my two children, she and I had passed the evening in our garden talking about the invasion of Kuwait, while watching Saddam Hussain on TV.

A few days earlier, Saddam had led his army on a summer dawn hike to Kuwait, and his action changed forever the lives of all Iraqis.

On that afternoon Umm Tawfiq stood at our door and she ordered me: "You must come with me to buy supplies."

I told her I had everything at home, but she insisted, saying that there won't be a grain of rice to be bought in an hour's time, neither a sack of flour nor a pack of detergent. America had led the UN to impose sanctions on Iraq.

She whisked me off in her blue Toyota Corona, and we spent the rest of that afternoon and evening looking for rice, lentils, flat beans, sugar, tea, flour, detergents, tissue paper, oil, cooking ghee and other commodities.

Essential items were disappearing quickly from all the stores in Baghdad they were practically vanishing before my very eyes.

I had no idea that a new page was turning in our lives as Iraqis. I could hardly imagine I was witnessing the death of our blue horse, the Iraqi dinar.

It was called a horse because it was a strong currency, backed with the second largest oil reserve in the world. It was termed blue because the colour of the Iraqi dinar was blue.

How was it possible for our blue horse to succumb to a single blow from the US and UN?

But things did not stop at that. The very next day, our daily bread, as we had known it all our lives, disappeared too. And despite Iraq's August heat, I imagined us living in Russia of the 1919, when bread became black and life unbearable.

We ate the black bread and discovered that it was baked from dough prepared with a mixture of brown flour, sawdust and crushed date pips.

From then on, things went downhill. Iraqis depended heavily on a measly ration of foodstuff that was distributed by the government.

On one occasion, there was a huge banquet for Ralph Ekeus, UNSCOM's chief arms inspector in Iraq. At the table, there was every conceivable delicacy. He was taken aback. At that moment, a Baath party official told him: "This is for you to understand that UN sanctions are against the Iraqi civilians and not the government you want to corner."

His words might as well have fallen on stones, as nothing happened to ease our lives. True, Saddam's government had made a grave mistake, but we were paying the price.

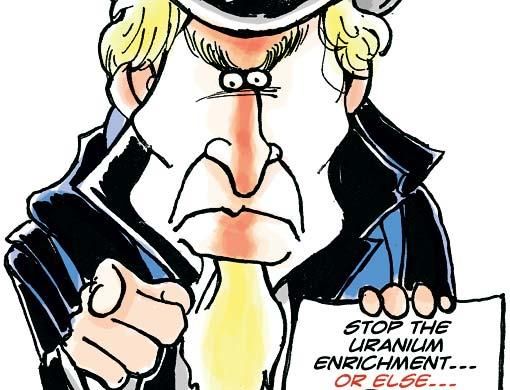

All this came back to me in a flash as I listened to the US President George W. Bush threatening Iran with "dire consequences" if Tehran goes ahead with its uranium enrichment programme.

I also remembered a great cartoon in the German magazine Der Spiegel, wherein Saddam in his army fatigues kicks Ayatollah Khomeini with his military boot. The caption read: "OK, you started it, now how do you pull out?" referring to the 8-year Iran-Iraq war.

Hunger

If the UN and the US impose sanctions on Iran, many Iranian babies will die, people will go hungry and Iran will suffer badly. I will rephrase Der Spiegel's caption: "How will you pull out this time if you start with Iran?"

Iran is not Iraq. Iran is a very determined country. And after Iraq and Lebanon, the US truly has a very small group of friends in these whereabouts.

The solution, alas, lies on the negotiation table.