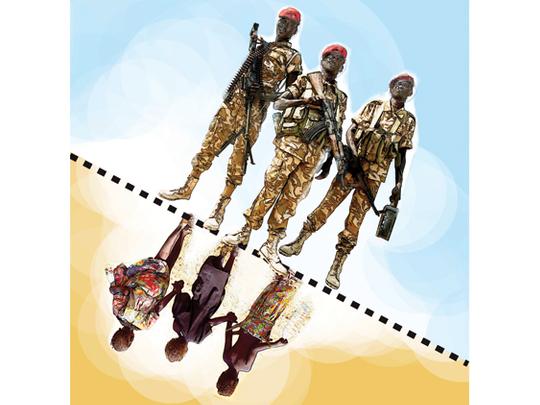

For today’s bitter draught of curdled ideals we turn to South Sudan, not so long ago a beloved newborn in the world of states. Last week, Secretary of State John Kerry announced that the United States was imposing sanctions on military leaders of the government and the opposition, both of whom, he said, had perpetrated “unthinkable violence against civilians.” Then, the U.N. mission in South Sudan released a report describing in detail systematic campaigns of rape and murder carried out by both sides.

Like Egypt, South Sudan was baptized in euphoria. After 50 years of an intermittent civil war that took the lives of 2 million people finally ended with a 2005 peace treaty with Sudan, southerners voted for independence in a delirious referendum in January 2011. At the celebration of that nation’s birth that summer, Susan Rice, then the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, proclaimed that South Sudan had demonstrated that “few forces on Earth are more powerful than a citizenry tempered by struggle and united in sacrifice.”

One thing we learn from watching citizens united in sacrifice tear one another to bits is the brevity of the binding moment of togetherness that reigns at a nation’s birth, or a movement’s triumph.

“The people and the army are one hand!” the protesters in Cairo’s Tahrir Square chant. So, briefly, were the Dinka and the Nuer, the major tribes and immemorial rivals of South Sudan. Sometimes the sense of common purpose endures, as it did in Israel and India or, more recently, in East Timor. Far more often, the warriors who emerge from the hills or the bush discover in politics a new form of warfare, to be waged against their tribal or ethnic or simply political rivals. Then the bloodletting begins.

The South Sudanese calamity feels almost inevitable in retrospect - “foreseeable, but maybe not avoidable,” in the words of Cameron Hudson, the former chief of staff to Scott Gration, President Barack Obama’s special envoy to Sudan. South Sudan’s leaders had spent their entire lives fighting a grinding, brutal war. When it came time to work out a series of compromises with Sudan, recalls Hudson, “They kept saying, ‘If we don’t get what we want, we’ll just go back to war.’” A favorite expression, meant literally, was, “My military uniform is still hanging in the closet.”

What’s more, John Garang, the closest thing South Sudan had to a founding father, died in a helicopter crash in July 2005. His place was taken by Salva Kiir, a fighter who, as Hudson puts it, “has no vision for the country” beyond his hatred for Khartoum. As a gesture of inclusiveness, Kiir, a Dinka, gave the deputy’s job to a Nuer, Riek Machar, a notorious turncoat who had spent years fighting for Khartoum against the southern rebels. The two finally turned on one another last summer, when Kiir fired Machar and much of his cabinet. After tensions rose to the surface at a party gathering in December, both sides sent their supporters into battle. A contest over political spoils then descended into the ethnic killing which spurred the Obama administration to declare a pox on both houses.

Could timely intervention by South Sudan’s many Western friends have prevented the mayhem? Perhaps not. One such Westerner, who has worked closely with the government, concludes that South Sudan’s leaders lived by a code of “kill or be killed”: Fearing a coup by Machar, Kiir mounted a pre-emptive coup of his own. South Sudan is now divided between a government led by Kiir and a wide array of semi-coordinated and well-armed forces fighting to control key cities and regions.

The category to which the South Sudan mess belongs is less Nave Self-Delusion than Circumstances Beyond Our Control. What is true, however, is that policymakers like Rice, national security official Gayle Smith, and others who had a long history with the rebel movement, shared the euphoria of the moment, and were outraged by what they saw as the cool realism of newcomers like Gration, who pushed the southerners hard to compromise with the government in Khartoum. Hudson says that the attitude of the unimpassioned pragmatists, which very much included Obama, was, “We’re about to guarantee the birthing of a basket case in the heart of Africa.” In this case, the skeptics were right.

Hudson says that Kiir and others consistently ignored whatever advice they received, thus bringing home how little leverage Washington had - despite years of unflagging support and billions of dollars in aid. It seems paradoxical to conclude that the United States, the United Nations, and other major international actors can do so little to shape the destiny of a powerless country. In fact, outsiders can do much more in a country like Tunisia or Ukraine, which has the capacity to help itself, than in a place like South Sudan, which has few roads in its endless hinterland, few educated people, almost no economy beyond oil and hardly anything outside of the capital city of Juba which deserves the name of “government.” South Sudan belongs in the category of Afghanistan and the Democratic Republic of Congo - epic undertakings in state-building into which billions of dollars seem to disappear like torrents of water in the desert.

Is the moral of the story that state-building, at least on an ambitious scale, is a contradiction in terms, best abandoned lest one raise expectations which cannot be satisfied? The only alternative conclusion is that halfway measures won’t work. A recent report by the International Crisis Group sharply criticizes the vast U.N. mission in South Sudan for focusing on “the extension of state authority” rather than the tougher and more confrontational job of demanding accountability for state abuses and protecting civilians. Of course, the regime would have resisted, and U.N. headquarters might have ordered the mission to back off.

Perhaps the only way outside powers could have prevented South Sudan’s leaders from making ruinous choices is to have made the choices for them. A U.N. “transitional administration” might have offered the South Sudanese desperately needed training in governance and slowly introduced its fighters to the uses of political authority. That system worked quite well in East Timor, though not so well in Kosovo, which spent over a decade in what felt like an infuriating tutelage. It has never even been attempted on a scale as large as South Sudan. I wonder if the world has the stomach for a heroic exercise in benevolent neo-colonialism.

The goal right now, however, is to stop the atrocities. The mass killing and rape in the town of Bentiu last month was coordinated by rebel commanders using a radio station to urge Nuers to target Dinka and other non-Nuer civilians. That, as the U.N. report noted, is an ominous sign redolent of Rwanda. Kiir and Machar have agreed to meet in Addis Ababa, but both men have ignored past agreements. Right now, South Sudan faces the very real possibility of both mass sectarian killing and a famine which could rival that which killed millions in Ethiopia 30 years ago - all less than three years from that blissful celebration of shared sacrifice. If anyone emerges a winner, it’s Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir.

The sanctions announced by Obama are unlikely to have much effect, though they may help galvanize the U.N. Security Council to impose more sweeping punishments. If anyone can intercede effectively, it’s probably South Sudan’s neighbors. An East African regional group, IGAD, played the key role in crafting the 2005 pact, and has worn out much diplomatic shoe leather since then trying to keep the agreement on track. IGAD officials have spoken of assembling a peacekeeping force, though that would be many months off.

South Sudan is not a story of neglect - quite the opposite. The United States, Britain, Norway, the U.N., and a number of states in East Africa, have all done what they can to care for this feeble infant. It hasn’t been enough. There may be no enough. Preventing mass starvation and mass slaughter in South Sudan may be the best the world can do.

— Washington Post

— James Traub is a fellow of the Centre on International Cooperation. He writes the Terms of Engagement column for Foreign Policy magazine.