Last week’s Brics summit in Durban feels like a relic of the previous decade. After a boom in the 2000s, the pace of growth in the celebrated economies of Brazil, Russia, India and China has slowed by 3 to 4 percentage points. Only China is now growing faster than the emerging market average.

Nowhere does the celebratory mood of the past decade, which inspired this motley group to launch the Brics summits, feel more absent than in South Africa. With its gross domestic product growing at a pace of 2.5 per cent, South Africa is on track to finish the year as one of the slowest economies in Africa.

This is an ironic turn. When The Economist called Africa the “hopeless continent” at the start of the millennium, South Africa seemed to offer a single bright spot. It brought debts and inflation under control, creating the stability required for growth. Now, it is stuck, and many other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, from Nigeria to Kenya, are growing twice as fast.

The ruling African National Congress (ANC) is relying heavily on a ‘liberation dividend’ to remain in office. Many South Africans have understandably ugly memories of apartheid and still embrace ANC leaders as authors of freedom, even if they are also the architects of stagnation. Yet the problems of inequality and unemployment are as acute as when the ANC promised ‘economic justice’ two decades ago.

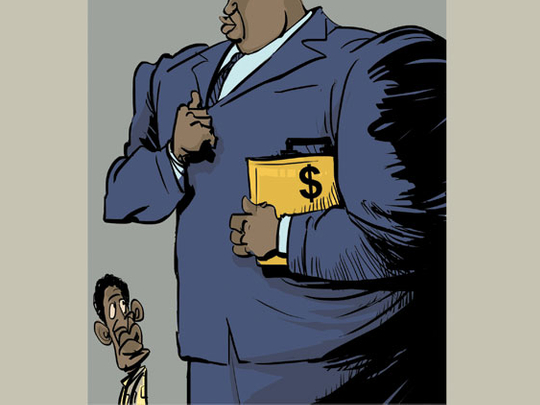

Today, the critical divide is economic, not racial. About half of the richest 20 per cent of South Africans are black; the problem is that the richest 20 per cent still control 72 per cent of the national income while the poorest 40 per cent have only 6 per cent — much the same as 20 years ago. South Africa is still one of the most unequal societies in the world.

Poor investment climate

Using the heavy hand of the state, the ANC created a black elite but not the business environment for economic growth. Discouraged by the high costs of labour and low productivity, South African companies are not hiring at home, and invest mainly in other African countries.

The share of South Africans holding a job is the lowest among all the leading developing nations. Investment represents just under 20 per cent of GDP, very weak for South Africa’s income level. The main source of growth is consumption, fuelled by income supports and civil service posts, which account for 85 per cent of the jobs created in the past decade.

The result is maximum government, minimum governance. Public services, such as water, electricity and schools, are all a shambles. The small number of taxpayers — 6 million in a nation of 50 million — complain that with the government spending so much on welfare, they get little in return for their taxes.

Mamphela Ramphele, head of Agang, a new opposition movement, says: “South Africa is now a poster child for how inequality can be expensive for everybody.”

Some South Africans see reasons for hope. Last year’s miners’ strikes may have sent a message that the liberation dividend is running out. That is propelling the rise of opposition parties and ANC figures — particularly Cyril Ramaphosa, ANC deputy president — who understand that the economy needs productive investment and a more business-friendly environment to grow faster. But the question is how long can the social fabric bear the strain of high levels of unemployment and inequality?

Every time I visit, there are cynics saying South Africa is at risk of becoming a failed state, yet it endures. The ANC’s long honeymoon is reminiscent of the Congress party, which led India to independence and lived off the liberation dividend for a quarter of a century before its mediocre performance led to political churn.

The Indian case would suggest time is running out. Further, in the present context, increasingly edgy international financial markets could force change on the ANC. With nearly 40 per cent of its bond market and half of its stock market owned by international investors, South Africa depends heavily on foreign capital.

The widening current account and fiscal deficits leave it vulnerable to a run on the rand. Against this backdrop, it is an awkward time to be focused on a summit of Brics, a club of the past decade’s stars, all facing very different challenges.

— Financial Times

Ruchir Sharma is head of emerging markets and global macro at Morgan Stanley Investment Management and the author of Breakout Nations.