The greatest geopolitical development that has occurred largely beneath the radar of America's Middle East-focused media over the past decade has been the rise of Chinese sea power.

This is evinced by President Barack Obama's meeting on Friday about the South China Sea, where China has conducted live-fire drills and made territorial claims against various Southeast Asian countries, and the dispute over the Senkaku Islands between Japan and China in the East China Sea, the site of a recent collision between a Chinese fishing trawler and two Japanese coast guard ships.

Whereas an island nation such as Britain goes to sea as a matter of course, a continental nation with long and contentious land borders, such as China, goes to sea as a luxury.

The last time China went to sea in the manner that it is doing was in the early 15th century, when the Ming Dynasty explorer Zheng He sailed his fleets as far as the Horn of Africa. His journeys around the southern Eurasian rim ended when the Ming emperors became distracted by their land campaigns against the Mongols to the north.

Despite occasional unrest among the Muslim Uighur Turks in western China, history is not likely to repeat itself. If anything, the forces of Chinese demography and corporate control are extending Chinese power beyond the country's dry-land frontiers — into Russia, Mongolia and Central Asia.

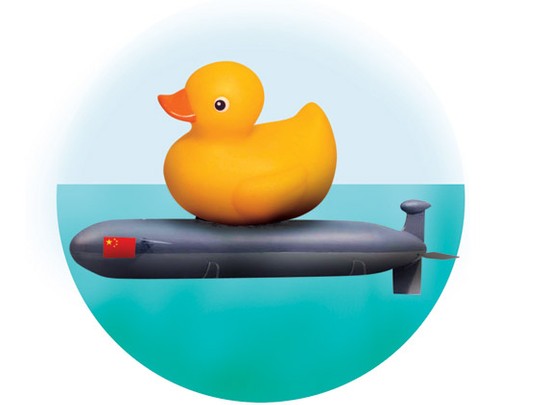

China has the world's second-largest naval service, after only the United States. Rather than purchase warships across the board, it is developing niche capacities in sub-surface warfare and missile technology designed to hit moving targets at sea.

At some point, the US Navy is likely to be denied unimpeded access to the waters off East Asia. China's 66 submarines constitute roughly twice as many warships as the entire British Royal Navy.

If China expands its submarine fleet to 78 by 2020 as planned, it would be on par with the US Navy's undersea fleet in quantity, if not in quality. If the US economy remains wobbly while China's continues to rise — China's defence budget is growing nearly 10 per cent annually — this will have repercussions for each nation's sea power. And with 90 per cent of commercial goods worldwide still transported by ship, sea control is critical.

The geographical heart of America's hard-power competition with China will be the South China Sea, through which passes a third of all commercial maritime traffic worldwide and half of the hydrocarbons destined for Japan, the Korean Peninsula and northeastern China.

That sea grants Beijing access to the Indian Ocean via the Strait of Malacca, and thus to the entire arc of Islam, from East Africa to Southeast Asia. The United States and others consider the South China Sea an international waterway; China considers it a "core interest".

Much like when the Panama Canal was being dug, and the United States sought domination of the Caribbean to be the preeminent power in the Western Hemisphere, China seeks domination of the South China Sea to be the dominant power in much of the Eastern Hemisphere.

Long-term plan

The US underestimates the importance of what is occurring between China and Taiwan, at the northern end of the South China Sea. With 270 flights per week between the countries, and hundreds of missiles on the mainland targeting the island, China is quietly incorporating Taiwan into its dominion.

Once it becomes clear, a few years or a decade hence, that the United States cannot credibly defend Taiwan, China will be able to redirect its naval energies beyond the first island chain in the Pacific (from Japan south to Australia) to the second island chain (Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands) and in the opposite direction, to the Indian Ocean.

To wit, China is building a blue water navy, even as it is helping to fund and construct ports in Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Pakistan. The Chinese will not have naval bases in these countries: India would find that far too provocative, and the Chinese are taking pains so others see their rise as peaceful and non-hegemonic.

Rather, these harbours will be visited by Chinese warships and will provide warehousing for Chinese consumer goods destined for the Middle East. China is building a far-flung trading network, ultimately to be protected by its warships — the British Empire refitted for a 21st-century era of globalisation.

America's preoccupation with the Middle East suits China perfectly. America is paying in blood and treasure to stabilise Afghanistan while China is building transport and pipeline networks throughout Central Asia that will ultimately reach Kabul and the trillion dollars' worth of minerals lying underground.

The United States should not consider China an enemy. But neither is it in its interest to be distracted while a Chinese economic empire takes shape across Eurasia.

This budding empire is being built on American backs: the protection of the sea lines of communication by the US Navy and the pacification of Afghanistan by US ground troops. It is through such asymmetry — America pays far more to maintain what it has than it costs the Chinese to replace it — that great powers rise and fall.

Robert D. Kaplan is the author of Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power. He is a senior fellow at the Centre for a New American Security and a national correspondent for The Atlantic magazine.