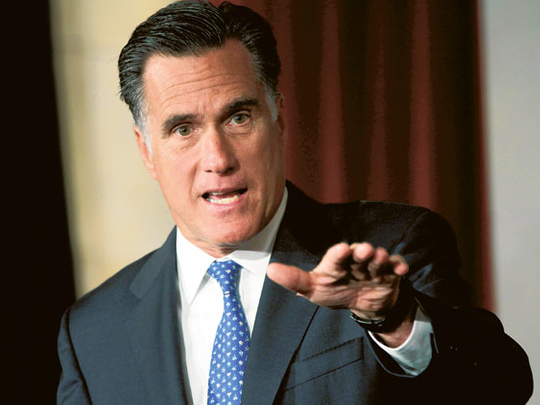

If the Republican primaries and presidential campaign have taught us anything, it is that Mitt Romney is not very good at politics. Incessant gaffes, strategic missteps, a paucity of policy prescriptions and a plethora of head-scratching tactical decisions have come to define his run for the White House. Quite simply, Mitt Romney is a bad politician.

But on Monday night (September 17), we learned something new - and profoundly unsettling - about him: he may very well also be a bad person.

I don’t use those words lightly, but I’m not sure how else to interpret the comments he made at a closed-door fundraiser that were posted online by Mother Jones. They are devastating. They suggest a level of meanness and divisiveness in Romney’s personal character that is disturbing ‑ even disqualifying for the nation’s highest office.

Look at how Romney classifies the 47 per cent of Americans who don’t pay federal income taxes:

“[They] will vote for the president no matter what. All right, there are 47 per cent who are with him, who are dependent upon government, who believe that they are victims, who believe the government has a responsibility to care for them, who believe that they are entitled to healthcare, to food, to housing, to you-name-it. That that’s an entitlement. And the government should give it to them. And they will vote for this president no matter what . . . These are people who pay no income tax . . .

“[My] job is not to worry about those people. I’ll never convince them they should take personal responsibility and care for their lives.”

This is a breathtaking statement: a fundamental misunderstanding of American social contract. Romney proposes here that the senior citizen living on a fixed income believes government has a responsibility to care for them ‑ rather than that government has a responsibility to fulfil its obligation to them after they spent years paying into social security and Medicare. He is saying that workers laid-off from their jobs, who rely on food stamps to feed their children and unemployment insurance to pay their rent, believe government owes them food and shelter, rather than getting some support at a time of dire financial need which their payroll taxes had paid for when they were in work.

Romney’s message to these voters, these 47 per cent of Americans, is not only “I am not going to seek your vote”; it’s “I don’t respect you.”

Worse than the crudeness of Romney’s argument is its remarkable lack of social empathy. The United States provides healthcare, food, housing and “you-name-it” to our fellow citizens not as a means of capturing their vote, but because this is fundamental to the basic social compact. That fact seems to elude Romney.

So what does this mean for Romney’s presidential prospects? Some conservatives seem overjoyed by the revelations - believing, it seems, that a “makers v takers” dividing line is a key to political success. Certainly, there is a cross-section of Americans who buy into Romney’s Ayn Randian views. There is also plenty of evidence from the world of political science that gaffes might get everyone ginned up on Twitter, but they don’t necessarily move voters.

This gaffe, though, has the potential to be different ‑ because it insults so many individual Americans. Romney’s Republican presidential forebears had the shrewd good sense to demonise easily stereotyped minorities: Richard Nixon took on the “shouters” and “demonstrators” in the 1960s, while Ronald Reagan attacked “welfare queens” in the 1980s. In his clumsy caricature, Romney has savaged just under half the electorate.

But the damage, once again, is self-inflicted: Romney has succeeded in highlighting the very things voters already don’t like about him: that he is not genuine, saying one thing in public and another behind closed doors; that he is so cosseted in wealth he does not understand and cannot relate to the challenges of ordinary Americans; that a callous streak runs through the private equity guy’s empathy deficit ‑ the outsourcer who “likes firing people”. The fact that these remarks were given at a private fundraiser to a group of fat cats only endorses these negative perceptions.

The biggest problem, though, may be the cumulative narrative: that it provides one more hit on Romney in a week in which he has done nothing right. First, there was his disastrous appearance on NBC’s Meet the Press, in which he flip-flopped on repealing Obamacare and bizarrely attacked his own vice-presidential candidate for supporting defence cuts last summer. Then came his crass intervention in the political debate that followed the violence in Libya and Egypt, in which he falsely accused the president ‑ on 11 September, of all days ‑ of sympathising with anti-American protesters. And even when that line of attack was comprehensively discredited, Romney doubled down on it the next morning. Finally, there was Sunday’s night Politico report chronicling the in-fighting and mismanagement threatening to cripple his campaign.

It was a terrible week for Romney and the Republican party ‑ one that suggested his campaign had acquired the hard-to-shake odor of loserdom. When that sense takes hold, every mistake, even minor ones, are magnified ‑ feeding into the notion that the Romney team is the proverbial gang that can’t shoot straight. We’ve seen this before, with George H.W Bush in 1992; with Al Gore in 2000; with Sarah Palin in 2008. A meme of smelly failure develops around a candidate and every story is fitted to that emerging narrative. For Romney, the narrative now is that he is running, as David Brooks put it in the New York Times, a “depressingly inept presidential campaign”.

It is hard to imagine how a presidential candidate could articulate such contempt towards virtually half the country that has not been as blessed with the advantages of being born into wealth and making more, as he has, and still hope to lead them. Whether or not Mitt Romney really is a bad person is perhaps irrelevant: he is clearly a bad politician ‑ and this last week has made it highly unlikely that he will get the chance to be a bad president.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd.

US columnist Michael A Cohen is author of Live from the Campaign Trail: The Greatest Presidential Campaign Speeches of the 20th Century and How They Shaped Modern America.