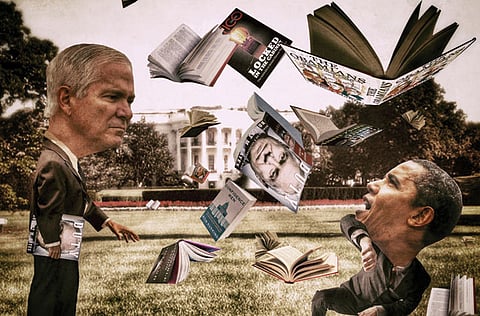

Robert Gates: Yet another tell-all memoir

Gates faults the president for his failure to rein in his staff

Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan wrote the soundtrack to my early childhood. You know the stuff. Seeger, sorrowful and mellifluous: “Where have all the flowers gone?” Dylan, querulous and un-mellifluous: “How many times must the cannonball fly?”

From this, you can probably deduce that I was a child of the American Left, of which little is now left. Even so, from time to time, I still find myself humming a few bars of a Seeger or Dylan song under my breath. I don’t mean to. I don’t even want to. It just happens. I had several such moments as I read former defence secretary Robert Gates’ new memoir, Duty. Maybe that is because Gates — whom no one would describe as a leftie, past or present — takes a stance on war that is not so far removed from the one taken by my anti-war parents in the early 1970s. Each time he visited US troops in Afghanistan, Gates recalls, he found himself “enveloped by a sense of misery and danger and loss”. American policy, he asserts, has become perilously over-militarised; “the use of force [is] too easy for presidents”. But viewed up close — far from the “antiseptic offices” of the White House or the CIA — war is never anything but “bloody and horrible,” and its costs are measured in “lives ruined and lives lost”.

Nodding along as I read, I found myself humming softly to myself. [Cue “Down by the Riverside.”] Gates ain’t gonna study war no more.

Which is just as well, since President Barack Obama ain’t gonna hire Gates no more. While his book is substantially more nuanced than early press accounts acknowledged, he is largely uncomplimentary towards the Obama White House. Gates was repelled by what he saw as the White House’s “aggressive, suspicious and sometimes condescending and insulting” attitude towards the uniformed military. But while much comment on Gates’ memoir has understandably focused on his account of the tortured state of civil-military relations, his critique of the president’s inner circle in fact goes far deeper.

Gates describes a White House populated by political hacks with little substantive foreign-policy knowledge, little understanding of how the executive branch works and less humility. He recalls Jim Jones, Obama’s first national security adviser, complaining to him and to Hillary Clinton that White House staffers were “advising the president on foreign policy issues that they knew nothing about”. Similarly, Gates recalls his own “chagrin” when Obama dispatched National Security Council (NSC) Chief-of-Staff Denis McDonough to check up on military efforts to aid earthquake-stricken Haiti. “I considered NSC involvement — or meddling — in operational affairs anathema,” he observes. “I had nothing personal against McDonough,” but “such staffers are almost always out of their depth.”

That is the polite critique. Gates is often less polite: Obama’s NSC took “micromanagement and operational meddling to a new level,” frequently leaving Gates “fed up”. Told that the NSC insisted it “had the pen” on a report on the status of military efforts in Afghanistan, Gates was “furious”: The NSC “might have the pen,” he insisted to National Security Adviser Tom Donilon, “but it couldn’t have its own foreign policy.”

Or at least it should not. Though Gates is frequently complimentary towards Obama himself, he clearly faults the president for his failure to rein in his staff. Obama allowed his NSC to become an “operational body with its own policy agenda, as opposed to a coordination mechanism,” he charges, and that its agenda was shaped mainly by short-term political considerations. At this point, in my perusal of Gates’s memoir, I found myself humming a different Pete Seeger song: “When will they ever learn ... when will they ever learn.” After all, Gates is only the most recent and the most senior in a long line of critics with a similar analysis of the Obama White House. I have even made this critique myself. (I too probably ain’t gonna get a job in the administration no more, though I continue to study war.)

Consider Vali Nasr, a former State Department official and respected Middle East expert — now dean at the Johns Hopkins Nitze School of Advanced International Studies — who describes his time in the Obama Administration as “a deeply disillusioning experience”. He describes Obama as a “dithering” president with “a truly disturbing habit of funnelling major foreign policy decisions through a small cabal of relatively inexperienced White House advisers whose turf was strictly politics”. There’s also, of course, former National Security Adviser Jim Jones, who is described in Bob Woodward’s book “Obama’s War” as convinced that senior White House political advisers were “major obstacles to developing and deciding on a coherent policy.” They “did not understand war or foreign relations,” but instead focused on “the short-term political impact” of the president’s decisions.

Such critiques are not just coming from those in national security fields. Commenting on the disastrous rollout of Healthcare.gov, a New York Times analysis concludes this failure “reveals an insular White House that did not initially appreciate the magnitude of its self-inflicted wounds, and sought help from trusted insiders as it scrambled to protect Mr Obama’s image”. Also in the New York Times, Paul Krugman shares his “sense that economic policy discussion in the WH has grown dangerously insular”.

Over and over, it is the same story: Read Edward Luce’s 2010 analysis in the Financial Times: “[F]ew can think of an administration that has been so dominated by such a small inner circle.” Or read James Mann’s The Obamians, recounting the frustration of cabinet officials marginalised by Obama’s “small inner circle” of former campaign aides. Or dip into Ron Suskind’s Confidence Men, describing “the dysfunctions of an often leaderless White House,” or Glenn Thrush’s recent Politico magazine article, ‘Locked in the Cabinet’, which notes that “the staffers who rule Obama’s West Wing often treat his Cabinet as a nuisance”. Or consider the conclusions drawn in a December National Journal article by veteran political reporter Ron Fournier: “President Obama needs to fire himself. Not literally, of course, but practically: He needs to shake up his team so thoroughly that the new blood imposes change on how he manages the federal bureaucracy and leads ... For all his strengths, Obama is a private, almost cloistered, politician surrounded by fawning aides who often put political tactics ahead of governing, protecting the president’s image with narrow-minded zeal.”

Here is the thing. No one likes “fawning aides” who “put political tactics ahead of governing”, but if the whole enterprise were a rousing success, we would hail the fawning aides as world-class geniuses. Imagine if Iraq had become a peaceful — or, at least, functional — state, if Afghanistan was stable and safe, if Pakistan was a reliable partner, if Syria’s bloody war had ended, if America wasn’t still trapped in a cycle of perpetual covert war against a poorly defined enemy, if the Russian “reset” had led to increased democracy and amity, if America’s domestic economy was thriving, if the Healthcare.gov rollout had produced nothing but happy customers, if Obama’s approval ratings were still at their 2009 high. Imagine! [Cue John Lennon.]

If Obama’s inner circle had led the president from triumph to triumph, who would not forgive a little micromanagement and “operational meddling”? Who would not forgive a little arrogance and insularity from the inner circle?

But that is not where we are. On the contrary, the president’s inner circle has presided over one policy failure after another. (No, I’m not going to list all those failures — I have written about many of them before and anyway it is just too depressing. And yes, I know, there have been some real successes — but they are mostly small, while the failures are mostly large. And yes, there are also some terrific people on the White House team, who have tried hard to offset the trends described by Gates and so many others. You know who you are, and bless you, and none of this is your fault.)

For a White House that appears to spend too much time thinking about politics rather than policy, here is the biggest failure of all: When it comes to public opinion, Obama’s presidency has gone down like a lead balloon. According to Gallup, Obama started out with an impressive 69 per cent job approval rating in January 2009. Now he is down to 41 per cent, lower than every past president’s approval ratings at this point in a second term, with the sole exception of Richard Nixon (who was mired in the Watergate scandal at this stage of his presidency).

If the political hacks cannot even get the politics right, why on earth does the president keep them around? When will he ever learn?

So here is what I am wondering: How many more memoirs like Bob Gates’ will it take before the president accepts that his critics might just be on to something? How many times does Obama have to hear the same criticisms — criticisms that come from his friends and supporters as often as they come from his political opponents — before he recognises that his presidency is in serious trouble and eases out the staffers who have been serving him so poorly?

“How many” [Cue Bob Dylan.]

“How many times can a man turn his head, pretending he just doesn’t see?

The answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind .... The answer is blowing in the wind.”

— Washington Post

Rosa Brooks is a Law professor at Georgetown University and a fellow at the New America Foundation. She served as a counsellor to the US undersecretary of defence for policy from 2009 to 2011 and previously served as a State Department senior adviser.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox