Last week, I participated in a fascinating debate at Cambridge University, featuring professor Richard Dawkins, an evolutionary biologist and fierce defender of atheism, and Dr Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury. Our subject: the incompatibility of religion with modern society and the challenges of the 21st century. Professor Dawkins and his camp asserted that religion is more dangerous than beneficial; that it is inherently 'evil'. For him, the thesis of a Creator of the universe is little more than a (bad) idea, a totally non-demonstrable aberration. His approach was aggressive, cutting-edge, quite dogmatic — religion is dangerous; we should thus be critical of its wild claims and hope that it simply vanishes. For someone who poses as a rational humanist, it was a curious posture: We should “eliminate” our adversary and seek its destruction in the name of “scientific” facts that alone are true and alone deserve respect. Could dogmatism be the child of rationalism as well as of religion?

However, first things first.

The “truth” of the non-existence of the Creator is nothing more than a postulate that cannot be demonstrated, as Dawkins, like many scientists and philosophers before him, recognises. It is nothing more than an “opinion,” a “belief,” just as much the product of “faith” as the opposing thesis. Atheist rationalism cannot claim for itself a monopoly of scientific validity for the simple reason that its view of God is not “scientific,” is not proof-based and is in fact an assemblage of hypotheses and probabilities. However, most dismaying is the attitude and the quasi-religious intellectual posturing of those who seek the demise of religion. If religious people deny paradise to their opponents or to “non-believers,” atheists would likewise seek to eliminate “dangerous” believers with their “childish” ways and their heads in the clouds. One would have thought that the only truly humanist attitude — midway between two theses that cannot prove themselves rationally and definitively — would be to make a commitment to ongoing debate, then actively pursue it out of concern for mutual intellectual integrity.

It is only through the opposition of ideas that we can learn to be self-critical, to work towards intellectual humility. The 21st century — and the atheists — needs the presence of religion, just as religion must deal with the real challenges and the thinkers of the day in order to sharpen the conscience and the intelligence of those who study the timeless sacred texts in a spirit of responding to the questions of their time. At Cambridge, when time came to vote, the audience found Dawkins and his supporters in the wrong. A strong majority of the more than one thousand students present concluded that religion has been and must remain an accepted reference to humanity.

Taking a position in public debates

However, beneath the question under debate lies a malaise as deep as it is revealing. In today’s world, religion can certainly make itself heard in civil society, but seemingly only in response to complex questions raised by the contemporary world or formulated by agnostic or atheist progressives. Religion is called upon to deal with issues ranging from science and evolution to the status of women and homosexuality. These are important questions and today’s religious conscience must address them and take a position in public debates.

Yet, the tone is polemical, with religion taking a defensive stance in a constant effort to justify itself. The historical balance of power has shifted, with the norms of progressive atheist or agnostic thought now being often unilaterally imposed. Pressure is increasing, to the point where we seem sometimes not too far removed from a new form of intellectual inquisition. Given these circumstances, it can be difficult to argue religion’s manifold contributions to the cultural evolution of mankind throughout history. The modern era has come to resemble a kind of “scientific,” “progressive,” “rational” (and irrational) courtroom in which religion itself is on trial for “belonging to the past.”

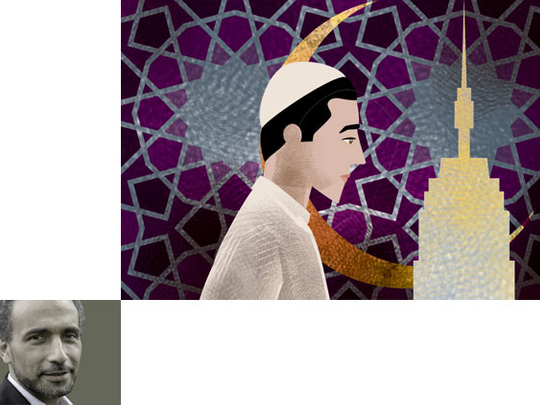

In the West, the new-found visibility of Muslim citizens and residents has transformed Islam into a prime target. Millions of Muslims — whose mosques, dress and religious practices are quite visible — pose a challenge to their fellow citizens, to intellectuals and politicians. Religion is back, an echo of an era that some people believed was gone forever. Muslims, as individuals, face the same constant pressure over the basic tenets of their faith, their practices and their positions on Sharia, on jihad, on terrorism, women, violence, headscarves etc.

Their religion and their presence are now defined as problems; they must devote much of their time in explaining exactly how this perception has no basis in fact. Politicians, intellectuals, journalists and simple citizens seem unable to grasp the idea that the presence of Islam and Muslims may be of some interest, that they may make some contribution to western societies. The most open-minded avoid pointing to problems, but few are ready to admit that Muslims may make a positive contribution (or that they may learn something from them). They urge Muslims to live a more normalised existence. In other words, to be far less visible. Some Muslims — lacking confidence — rush into the breach. What cannot be conceived is a positive presence of Islam in the West, based on participation and contribution. No. Islam remains a problem to be dealt with and little more.

And yet, the Muslim tradition, like all philosophies and religions, summons the human conscience to concern itself with the meaning of life, with human dignity, with respect for human dignity against a background of dangerous practices such as genetic engineering and the growing legalisation of torture. Muslim spirituality, from the traditional schools of jurisprudence to mystic circles (Sufism), invites the conscience and the heart to reflect upon the terms and conditions of the liberty of beings, to contemplate with detachment.

It even calls into question the excesses of consumerism and commercial servitude. Can there be nothing to share with citizens whose spiritual traditions and practices give pride of place to responsibility and to the imperative of becoming a subject, a whole being, a responsible adult? Just as do philosophies, other religions and spiritual traditions, Islam asks fundamental questions about the ultimate goals that we assign to our activities, be they political, economic or scientific and to the means (technological, military, etc.) we employ to reach them.

We must not and cannot seek to convert others, nor to restrict knowledge and freedom, but to raise serious questions about ends, about ethics, about our personal dignity and that of all beings and of Nature itself. At the heart of Islam lies an imperative of solidarity that our well-developed individualism cannot do without: The rights of the poor must become an integral part of the human conscience’s duty.

Full-fledged critical subjects

Can our societies do without this kind of reflection? Don’t they have any need for a wholesome debate on ethical principles and ultimate goals? Does religion in general and Islam in particular have nothing else to offer than the interminable justifications that lie at the core of a pernicious ideological conflict? Will the West at last become aware of the rich diversity that lies within it? Will it be able to find a proper way to make use of the presence of Islam and of Muslims in its midst by understanding their positive contribution to the great philosophical debates that our era so desperately needs? Will it be able to reconcile itself with its own values of pluralism and equality? And will Muslims be able to free themselves from a posture shaped by a sense of the victimhood of a visible minority, by their feeling that they are objects of the negative perceptions of their fellow citizens? Will they muster the courage to become intellectually, scientifically, artistically and ethically visible as full-fledged critical subjects, as believers no less free for being so?

The horizon of our common future lies at the confluence of these two sets of questions. West and East. Such is the fate of the rich and poor; the existential question we all must resolve.

Tariq Ramadan is professor of Contemporary Islamic Studies in the Faculty of Oriental Studies at Oxford University and a visiting professor at the Faculty of Islamic Studies in Qatar. He is the author of Islam and the Arab Awakening.