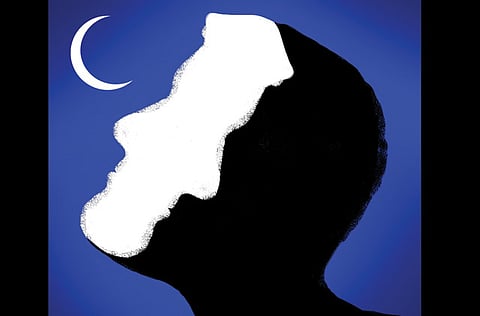

Ramadan: A time for introspection

Ramadan is a month of renewal, of critically summing up our lives

The month of Ramadan is at hand and with it, Muslims will be entering into one of the finest and most beautiful schools of life. The fasting month is a school of faith, spirituality, awareness, giving, solidarity, justice, dignity and unity. Nothing less. It is the month when introspection among Muslims should be deepest; the month of their greatest contribution to humanity. The month of Ramadan is the world’s most widespread fast and yet its teachings are minimised, neglected and even betrayed (through literal application of rules that overlooks their ultimate objective).

Small wonder then that we should return to the subject and as the fasting month returns each year, we too must repeat, rehearse and deepen further our understanding of what Ramadan teaches us, of this school of divine nearness, of humanity and dignity. The fast is each individual’s quest for the divine; it asks of each of us to look beyond self. Ramadan is, in its essence, a month of humanist spirituality.

During the fasting days, we are called upon to abstain from eating, drinking and responding to our instincts, to help us turn inward, to our heart and the meaning of our lives. To fast means to experience sincerity, to observe our shortcomings, contradictions and failings; no longer to attempt to hide or to lie and instead to focus our efforts on the search for ourselves and for the meaning and priorities of our lives. Beyond food, fasting requires us to examine ourselves, to recognise our limits humbly and to reform ourselves ambitiously. It is a month of renewal, of critically summing up our lives, our needs, our forgetfulness and our hopes. We must take time for ourselves, to look after ourselves, to meditate, to contemplate, simply to reflect and to love.

Seen in this light, the month of Ramadan is the best possible expression of anti-consumerism: To be and not to have, to free ourselves of the dependencies that our consumption-based societies not only stimulate but magnify. In calling upon us to master our instincts, the fast calls into question the modern notion of freedom. What does it mean to be free? How are we to find our way to a deeper freedom and move beyond what we crave? The true fast is at odds with appearances.

The tradition of fasting was prescribed, the Quran tells us, for all religious traditions before Islam. It is a practice we share with all spiritualities and religions and as such it bears the mark of the human family, the human fraternity. To fast is to participate in the history of these religions, a history that possesses a meaning that has its own demands upon us and that is shaped by destinies and by ultimate goals. A unity of spiritual descent, of transcending everything that is strictly human, that unites all belief systems, all faiths. Islam places it in the meaning of tawhid, the recognised and acknowledged ‘Oneness of God’ that opens onto human diversity by virtue of how it is experienced and lived. The same holds true among Muslims. The time frame and the rhythm of those who fast are similar; the cultures of fast ending, of meals and of the night are diverse. In other words, there is unity in meaning, diversity in practice. The month of Ramadan carries with it this fundamental teaching and reminds Muslims, whether Sunni or Shiite, irrespective of which school they follow, that they share the same religion and that they must learn to know — and to respect — one another.

The coming month is one of dignity, for ‘Revelation’ reminds us that a human being is a creature of nobility and dignity. “We have bestowed dignity of the children of Adam [all humankind]”. Only for them, in full conscience, is fasting prescribed; only they are called upon to rise to its lofty goal. Human beings must undertake the fast in a spirit of seeking nearness to the unique; in a spirit of equality and nobility among their fellows, women and men alike, and in solidarity with the downtrodden. The core of life thus rediscovered is this: To return to our hearts, to reform ourselves in the light of what is essential and to celebrate life in solidarity; to experience deprivation as desired; to reject poverty as imposed and degrading. Our task is one of self-mastery; we must lift ourselves up, sever our ties, become free and independent, above superficial needs, and concern ourselves with the true, down-to-earth needs of the poor and the needy. The month of Ramadan is thus a place of exile from illusion and fashion and a pilgrimage deep into one’s self, into meaning, into others. To be free of ourselves and at the same time to serve all those imprisoned by poverty, injustice or ignorance.

Muslims spend 30 days in the company of this month of light. If only they could open even wider their eyes, their hearts and their being to receive the light and offer it in the form of the greatest gift of their spiritual tradition to their sisters and brothers. They are called to exercise self-control and to give, to meditate and to weep, to pray and to love. Truly to fast is to pray; to pray is to love.

Tariq Ramadan is professor of Contemporary Islamic Studies in the Faculty of Oriental Studies at Oxford University and a visiting professor at the Faculty of Islamic Studies in Qatar. He is the author of Islam and the Arab Awakening.