In March 1947, US President Harry Truman was preparing to launch a major foreign policy orientation that would define US foreign policy in the post Second World War era and beyond. It was based on active American involvement in world affairs for the purpose of containing, by force if necessary, the spread of communism around the world.

To secure the support of the American people for the dramatic sweep of the new policy Truman readily understood that he needed to define his doctrine in terms of broad commitment to defend American values of freedom and individual liberties.

But he also wanted Congress to approve a specific commitment to provide huge economic and military support to Greece and Turkey whose pro-Western governments were threatened by communist insurgencies.

Truman sought and received advice from Congressional leaders as he prepared to launch his doctrine. Truman was most impressed with the advice he received from Senator Arthur Vandenberg: "Mr President," said Vandenberg, "the only way you are ever going to get this is to make a speech and scare the hell out of the country".

Truman proceeded to scare the country. He painted the crisis in Greece in dark foreboding terms: "The very existence of the Greek state," he said, "is today threatened by the terrorist activities of several thousand armed men, led by communists, who defy the government's authority..."

He linked the security of the US to a broad anti-communist crusade, a war on the dark forces of totalitarianism: "Totalitarian regimes imposed on free peoples, by direct or indirect aggression," he said, "undermine the foundations of international peace and hence the security of the United States".

He painted the world in simplistic foreboding Manichean terms, and called on peoples of the world to choose between the good side - Western democracies and free market capitalist economies - and the bad side - communist regimes: "At the present moment in world history nearly every nation must choose between alternative ways of life. The choice is too often not a free one," he said.

"One way of life is based upon the will of the majority, and is distinguished by free institutions..." Truman declared. "The second way of life is based upon the will of a minority forcibly imposed upon the majority. It relies upon terror and oppression...."

Truman then proclaimed the new foundations of American foreign policy, the Truman doctrine: "I believe that it must be the policy of the United States," he declared, "to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures."

A theoretical framework provided the necessary rationalisation for the application of the Truman doctrine. US Undersecretary of State Dean Acheson articulated the theory that came to be known as the domino theory.

He told Congressmen and State Department officials that what was at stake was much more than the survival of the Greek and Turkish governments. If these countries were allowed to fall to communism, he forebodingly warned, other countries, in a domino-like effect, from Iran to India, would fall to communism.

The Truman doctrine was as sweeping a commitment as the US had ever made. It was the official declaration of a Cold War that defined the balance of power in international relations for over 40 years. And it was based on the exaggeration of the Soviet threat and the exploitation of the American people's fear of that threat.

Secretary of State George Marshall believed that Truman overstated the case. Even George Kennan, the American diplomat in Moscow whose analysis articulated the need to contain the Soviet Union, was surprised by the sweeping scope of the Truman Doctrine which made containment official American foreign policy.

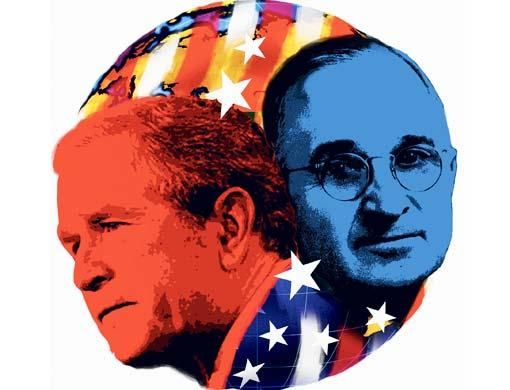

In articulating his own doctrine George W. Bush played on the fear engendered by the September 11 tragedy, exaggerated the threat of countries such as Iraq, and distorted the facts. His administration resorted to fabrications and falsehoods to justify its war policy.

Reactive

The Truman doctrine was reactive in that it committed the US to act to contain communist threat wherever it manifested itself from Korea to Vietnam; the Bush doctrine is pre-emptive in that it commits the US to strike first at targets of its own choice in a perpetual and ill-defined so-called war on terror.

Like Truman, Bush articulated a simplistically dark Manichean view of a world perpetually divided by the opposing forces of good and evil, and in which unless one sided with the forces of good, one is necessarily grouped with the forces of evil: "Every nation, in every region, now has a decision to make." Bush told the American Congress on September 20, 2001. "Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists."

Borrowing the Truman doctrine's theoretical frame of rationalisation, the Bush administration invoked the domino theory to justify its preemptive war strategy.

In August 2006, Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfeld told the Senate Armed Services Committee: "If we left Iraq prematurely, the enemy would tell us to leave Afghanistan and then withdraw from the Middle East. And if we left the Middle East, they'd order us and all those who don't share their militant ideology to leave what they call the occupied Muslim lands from Spain to the Philippines."

And eventually, he warned, America will be forced "to make a stand nearer home".

The Bush doctrine is inherently aggressive. It seeks not simply to contain the enemy, but to undertake "unwarned strikes" to swiftly defeat the enemy from "a position of forward deterrence".

It also guarantees perpetual confrontation. It is committed to maintaining global American hegemony against all challenges: "America has," Bush said, "and intends to keep, military strengths beyond challenge."

Prof. Adel Safty is Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Siberian Academy of Public Administration, Novosibirsk, Russia. He is author of 'From Camp David to the Gulf', Montreal, New York.