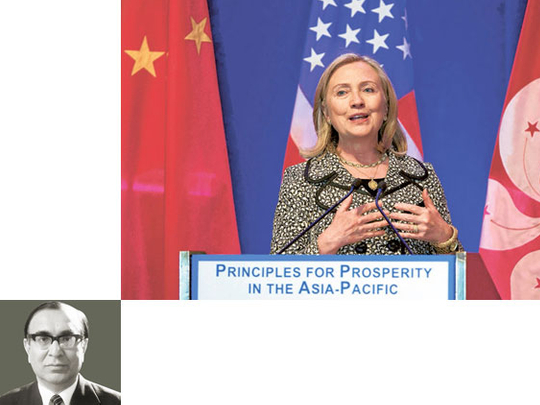

The tangled Pakistan-US relations seem to be poised at a decisive point. On October 20, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton arrived in Islamabad accompanied by the new US Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Martin Dempsey, and the new Director of CIA, General David Petraeus. The powerful trio had earlier sent a stern message from Kabul that made it clear that this historical relationship now hinged on Pakistan complying with American demands related to the Afghan conflict.

In the impending battle of wills, the Pakistan army took the unprecedented step of making it known that its dependence on the US for military assistance need not determine Pakistan's response as it was prepared to do without it.

The differences on Afghanistan that have brought the relationship to a make-or-break point are perhaps inevitable when the stronger party looks at that ravaged country largely from the standpoint of a ‘superpower' pursuing a global strategic agenda and a middle-size neighbour of Afghanistan seeks peace and economic cooperation across a troubled 2,500km border straddled by the same warlike tribes.

In Pakistan's view, the 10-year-old military operations have not delivered a solution warranting a shift to a search for a negotiated settlement while military action is perceptibly wound down. Accepting "reconciliation" as its ultimate aim, Washington believes that it first needs to bludgeon the recalcitrant Afghan tribes with more force to make them more amenable to the US objectives at the eventual peace talks.

Expected to play a role that is probably beyond its military capacity, Pakistan argues that the Pashtun tribes grouped under the so-called Haqqani network will absorb the pain and become more, and not less, intransigent with this strategy. The best guess is that the Americans fear that this particular band in the spectrum of resistance would not accept a solution built around smaller but lethal permanent American military bases capable of projecting power far and wide even after 2014.

During her visit, Clinton combined tough messages with readiness to re-set relations to Pakistan's advantage if Islamabad were to take strong measures to ‘squeeze' the Taliban, especially the Haqqani faction, hard in ‘days and weeks' and not longer. The New York Times' report highlighted Clinton's ‘blunt warning' that "Pakistan would face serious consequences if it continued to tolerate safe havens for extremist organisations that kill Americans". Side-stepping stark choices, the Pakistani leadership — civil and military — reiterated its preference for a policy of talking to the insurgents than the decision to first ‘fight, fight' and then proceed to ‘fight and talk'.

Pakistan shared its present assessment of the prospects of initiating negotiations with the Taliban while cautioning the Americans that it was in no position to guarantee their outcome. In welcome remarks made in her public appearances, Clinton virtually disowned some of the grave allegations against Pakistan made by Admiral Mullen in his last testimony to a Senate sub-committee, allegations that had deepened the crisis in relations.

There is a danger that the current difference in perspectives may, somewhat irrationally, tar the bilateral Pakistan-US relations permanently. On the eve of Clinton's visit, Bruce Riedel, who gave the newly elected President Barack Obama his first Pakistan briefing — heavily loaded against Pakistan according to published sources — wrote another polemic in The New York Times under the title "A new Pakistan policy: Containment". The op-ed piece revealed that Obama was being asked by his experts to cut Pakistan's military and intelligence services to size — objectives going beyond problems in Afghanistan.

Foreign policy

"It is time," Riedel observed, "to move to a policy of containment [of Pakistan], which would mean a more hostile relationship". Amongst the reasons cited for this shift to focused ‘hostility', Riedel enumerated lack of harmony in strategic interest; Pakistan army's control of strategic policies; and the need to curtail the Pakistan army's ambitions until "real civilian rule returns and Pakistanis set a new direction for their foreign policy". If this is a true portrayal of the real intentions of the American establishment, Clinton's visit may not really ‘reset' the relationship.

In her public interaction with assorted groups from the media and the civil society, Clinton was rather non-committal on Pakistan's long standing requests for greater market access and on attaching Afghanistan-related military preconditions to the actual disbursement of the promised economic assistance. These conditions reinforce the popular perception that Washington is basically exploitative in using Pakistan to achieve its goals in the region and remains insensitive to Pakistan's huge human and material losses in the ‘war against terror'.

At present, Pakistan's military is an important factor in shaping Pakistan's foreign and security policy. Apparently, American strategic thinking continues to postulate an underlying distinction between a compliant political government and a reluctant military sticking to its own perception of the regional situation. Notably, Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gilani received the formidable American delegation with the Pakistan army chief, General Ashfaq Pervez Kiyani and the Intelligence Chief, Ahmad Shuja Pasha, at his side. Pakistan has to find its own balance in civil-military relations depending on its perception of national needs and not the requirements of any outside power.

Tanvir Ahmad Khan is a former ambassador and foreign secretary of Pakistan.