This is all very exciting. For the first time, we have managed to land a spacecraft on a comet and congratulations are in order to everyone involved. The European Space Agency (Esa) spacecraft Rosetta has been approaching a comet called 67P for the past few months and recently descended into near orbit — just six miles (9.6km) away, or as far away as a small jet aircraft flies above the Earth.

The mission was agreed more than 20 years ago: The journey has taken just over 10 years, covering a distance of four billion miles — that is a million times the distance to the centre of the Earth or the equivalent of eight thousand return trips to the moon. The journey involved “swinging by” Mars once and the Earth three times, each time gaining a gravitational shove in the right direction, and also a hibernation period of two-and-a-half years to conserve energy. Along the way, Rosetta has studied two planets, two comets and two asteroids.

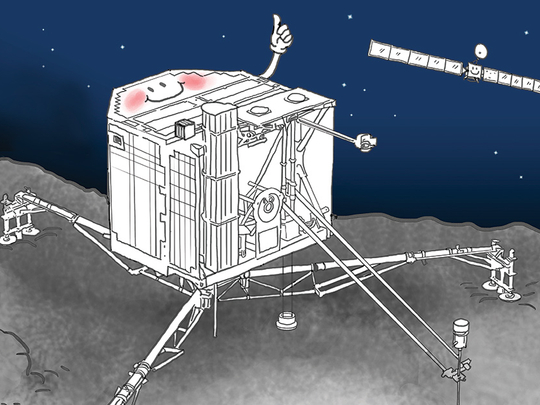

Today, its lander Philae successfully touched down on the comet, using a harpoon or two to attach itself to the surface to avoid bouncing off into the vastness of space again. Rosetta is about the size of a minibus, with the two solar panels that power it each being about the length of four cars. Philae is about as big and heavy as a washing machine.

The comet’s full name is 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, named after the two Soviet scientists who discovered it in 1969 while analysing photographs from powerful Earth-based telescopes. The comet is about two-and-a-half miles across, or the size of a small English village. Over the next few days, Philae’s onboard robotic laboratory will conduct a number of experiments on the rock and ice nearby: The “artificial intelligence” required to do this is similar to that in domestic washing machines, where pressing one button can activate a complex series of actions.

Photographs of the comet taken by Rosetta in August, from between 70 and 500 miles away, can be seen. Note that Rosetta and the comet are both inside the solar system, travelling at 34,000 mph and more than 300 million miles away from us, between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. This Esa mission has cost almost £1 billion (Dh5.77 billion) and there has been some involvement by Nasa.

As Esa says, the cost should be put into perspective: It is half that of a modern submarine or the same as three of the latest Airbus jumbo jets and has been spread over 20 years of scientific and industrial activity, creating thousands of jobs. Several British companies and universities have been involved in this cutting-edge project. Still, why should we spend so much money studying a large rock in space?

First, and most importantly, we know that comets — and there are billions of them in the outer regions of our solar system — are debris left over from the formation of that solar system, between four billion and five billion years ago. They are frozen relics from a bygone age. Furthermore, there is evidence that millions of impacts by comets, composed of rock and ice, delivered enormous quantities of additional water to the inner planets.

Only the Earth retained large amounts of water, of course. So studying the composition of comets significantly increases our understanding of the origins of our planet and our solar system.

Second, comets are known to include organic molecules, while meteorites have been known to contain amino acids — the building blocks of life. More detailed analysis of comets will help answer questions about the origins of life on Earth: Could the first living entities on Earth, or their building blocks, have been delivered by extraterrestrial arrivals such as meteorites or comets?

There are other spin-off benefits, such as the development of space and low-energy technology, some of which will eventually find its way into domestic gadgets and be used to benefit humanity, as well as the usual unpredictable benefits of good science.

However, another reassuring aspect of this mission, that has succeeded in finding a needle in an interplanetary “haystack”, is that it increases our confidence in being able to meet and divert any asteroid or comet that may collide with Earth and wipe us all out. Something we may one day have cause to be grateful for!

— Guardian News & Media Ltd