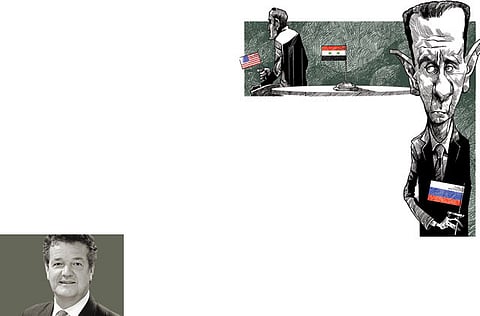

Neither side in Syria wants to talk at the moment

Putin relishes his blocking vote on peace in Syria

As the war in Syria intensifies, it is hard to think that the only end to the endless killing and slaughter is a political settlement that will include both sides. This week’s deeply divided G8 summit did succeed in charting the outline of what kind of political solution may be required, even if it failed to do much about what is happening on the ground and any notion of supporting a ceasefire failed miserably and did not even get close to the table.

The G8 members back different sides in this war. Russia supports the government, the West supports the opposition and both sides allege atrocities by the other. Russian President Vladimir Putin refused to stop backing the Bashar Al Assad regime and asked incredulously the other seven members of the G8 why the West was supporting barbarians and cannibals, referring to the shocking video in which a commander of a fringe group supporting the opposition slaughtered a government soldier, cut out his heart from which he ate a mouthful.

In reply, British Prime Minster David Cameron summed up his allies’ horror at the atrocities perpetrated by the government, including the use of chemical weapons. He repeated the European view that Al Assad has “blood on his hands” and that he cannot be part of Syria’s political future.

‘Transitional governing body’

Nonetheless, the G8 managed to continue the international consensus achieved at the Geneva conference in July 2012, and pledged to back a “transitional governing body”, maintain Syria’s public institutions (learning from the failure in Iraq) and to work together to “rid Syria of terrorists and extremists”.

Other references in the meeting included specific statements that the transitional government would have full control of the armed forces and police. The G8 also promised to “maximise the diplomatic pressure” to bring all sides to the table as soon as possible and support a new non-sectarian government in Syria. The closest it got to events on the ground was to condemn the use of chemical weapons “by anyone” in Syria and seek a UN investigation into their alleged use, since Russia refused to agree that the evidence of their use was strong enough.

Putin’s illusion

The G8 focus on Syria allowed Putin to enjoy his hour in the sun. As the president of a near-bankrupt ex-superpower, Russia has very little global influence, so Putin is delighted to have a blocking vote on Syria, which has plunged him back to the illusion of the glory days when the USSR was one of the world’s two superpowers. But Putin has taken a typically opportunistic and short-term view of what to do in Syria and by backing Al Assad he has wrecked any hope of being taken seriously in all other global arenas. This is important for Russia, but may not matter much to the ex-KGB officer-turned-strongman and his mafia and oligarch allies who run Russia to their mutual benefit.

However, all the talk at the G8 on the shores of Northern Ireland’s Loch Erne did not include anyone from Syria. The Syrians are totally wrapped up in the fighting and neither side wants to talk at present. They both want to improve their positions on the ground before any negotiation starts. The government has just captured Al Qusayr and feels that another push may recapture Aleppo, Syria’s largest city. The opposition’s substantial gains in Syria’s rural areas in the north and south have been offset by the stalemate in the cities.

The government has been greatly encouraged by its victory in Al Qusayr, by the very effective support it received from Iran and Hezbollah and by Russia’s continued diplomatic backing and supply of arms. Al Assad and his generals will see no reason to bargain away what they expect they will be able to keep by force of arms.

Stronger political presence

The opposition recognises that it is politically weak, as it continues to be plagued by divisions between the leaders inside Syria, who are fighting for their lives every day, and the more academic politicians who are outside the country. It may be waiting for the West to implement a no-fly-zone, which will allow the internal leadership to find a secure base from which they can both manage more effective control over the troops and also build a stronger political presence with external politicians.

The new Iranian President, Hassan Rouhani, served as Iran’s National Security Adviser for many years and is well aware of the Iranian view that it is an embattled nation surrounded by enemies, with the additional concern that the US has bases in the Gulf and in Afghanistan, which are able to look at Iran from both sides.

Therefore, the election of the more pragmatic Rouhani to the presidency will not change things much in Syria. It may be that Rouhani will see the advantages of Iran attending a ‘Geneva 2’ conference in order to gather diplomatic credit for a new style of operation, but he continues to back Al Assad’s presidency and Iran continues military and financial support to Syria.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox