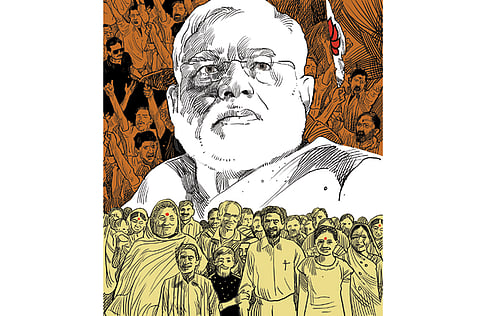

Modi: Saviour or sectarian?

The likely new prime minister of India is wildly popular among his supporters but others fear and distrust him

Save a single exception typically, an academic every person of Indian descent known to me within a half-mile radius of my house wants Narendra Modi to be the next prime minister of India. Admittedly, this is not a large sample: it consists of a few shopkeepers who sell groceries and newspapers in my small part of north London. Nor is it a very balanced sample: like many small shopkeepers in Britain, they have their origins in the state of Gujarat and they are all, I think, Hindu by tradition if not observance. In other words, they share Modi’s language, customs and religious identity and, like him, believe that entrepreneurship and hard work will deliver a better future.

You might well ask, “If people such as these won’t support Modi, who will?” But the striking thing is their certainty and enthusiasm. Not only are they convinced that Modi will win, they also believe his victory will re-energise the Indian economy, root out the corruption of politicians and public officials and clarify the country’s purpose. I can’t remember another politician inspiring such belief among the Indian diaspora; perhaps former Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi did during India’s triumph in the Bangladesh war, but it was never repeated not by her or her son, Rajiv, and certainly not by Rajiv’s son, Rahul. Rahul is the latest and perhaps last hope of a Nehru/Gandhi dynasty that has produced three prime ministers; very few people expect him to be the fourth. His leadership of the Congress party’s campaign has been reluctant and inept and, if recent polls are to be believed, the number of Congress MPs will have shrunk to a record low when the final votes in India’s general election are counted next month.

A comparison of the likely loser and winner in the election should gladden the heart of anyone who believes in upward social mobility. Rahul’s ancestry is a mixture of Kashmiri Brahmin, Parsi and Italian; his family has provided India with political leaders since the 1920s; he went to elite universities Harvard, Cambridge; his mother, Sonia, pulls the strings in the party that appointed him to its hierarchy. Modi, by contrast, comes from a low-caste family in a small Gujarati town and left school to help his father run a tea stall at the local railway station, where he would greet every stopping train with a kettleful of tea, mixed in the Indian way, and call out “chai, chai, chai” (tea) as he ran along the platform touting custom. His command of English is poor (though improving), which means the power of his rhetoric is largely lost to a world audience beyond those who speak Hindi. He sounds fluent and forceful much more so than Rahul, who, at 43, is 20 years younger.

In a country divided by both class and caste, his is a remarkable story: the chaiwallah (tea seller) who rose to become his state’s chief minister and eventually (if the predictions come true) the leader of a fifth of the world’s population. Nonetheless, the egalitarian heart isn’t gladdened. Modi, in the words of his not unsympathetic biographer, Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, is probably India’s “most reviled political leader” not widely reviled, otherwise he’d be dished by the voters, but deeply so among a particular class. Of course, religious minorities, such as India’s 180 million Muslims, might reasonably fear him as a Hindu nationalist, but the loudest revulsion comes mainly from elsewhere, from the Anglophone intelligentsia who think the politics of religious identity will wreck India’s fragile harmony as anavowedly secular state. Most of my friends in India come from this class, and who am I, as an outsider, to doubt that their apprehension is well grounded?

Not many outsiders to Britain, after all, ever quite understood why former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher was so loathed by a minority. (“What’s your problem? She’s turned your country around, hasn’t she?”) But the charge against Modi inspires a much deeper distrust and leads, for example, to his opponents comparing him to Hitler in his mission of national salvation. He is a genuinely polarising figure: the gulf between his supporters and critics seems unbridgeable. Even at book festivals, those generally herbivorous events, there have been bitter rows on and off the platform that eclipse even the arguments of the miners’ strike.

The central question is what Modi as chief minister of Gujarat did or didn’t do in the anti-Muslim violence that erupted in his state in February 2002, after a train carrying Hindu pilgrims was set ablaze by unknown arsonists and around 60 passengers died. Hundreds of Muslims were killed in the riots that followed estimates range between 900 and 2,000 and the accusations grew that Modi’s government hadn’t tried hard enough to restrain the rioters; it might even have encouraged them. An investigation by India’s supreme court cleared him of deliberately permitting the violence, though an observation in court by one of its judges that when women and children were going up in flames, Modi looked away like a modern-day Nero has clung to him ever since. He has steadfastly refused to discuss his role in the riots or express regret, and directs any questioner to the findings in the supreme court’s report.

No compelling evidence has been found to contradict these findings, but with Modi’s promotion from a provincial to a national figure, the question has never died away.

A recent tactic by his supporters has been to suggest that he’s being unfairly picked on. Communal riots are not unique to Gujarat, but the chief ministers of other states have not been blamed when pogroms have erupted on their watch. Most famously not a chief minister but a prime minister there is the case of Rajiv Gandhi. After his mother, Indira, was assassinated by her Sikh guards in 1984, mobs roamed Delhi murdering Sikhs in revenge. By way of explanation and excuse, Rajiv said: “When a mighty tree falls, it’s only natural that the earth around it shakes a little.”

As a reporter there at the time, I can attest to some of the shaking that went on. In a working-class Delhi suburb called Trilokpuri, for example, a 1,000-strong mob went on hunting Sikhs for 30 hours, beating them to the ground when they found them and then dousing them with petrol and setting them alight. About 350 Sikhs died there in the two days following Mrs Gandhi’s death. The police didn’t intervene. When I went soon afterwards, the scorch marks were visible on the ground and witnesses spoke of how Congress activists, including two or three MPs, had gathered the mob and provoked it by making fiery speeches and handing outbooze.

How much did Rajiv know of this, had he sanctioned it, and did he choose not to enquire? The question of the Congress party’s implication in the killings was pursued half-heartedly for a time and then forgotten. Thirty years have passed. Rajiv is dead. Nobody has gone to jail.

Perhaps the same oblivion will one day extend to Modi and the Gujarat riots of 2002. Prime ministers have to be worked with, their power acknowledged. The UK lifted its 10-year boycott of him in 2012, followed by the EU a year later. The US, which has denied Modi a visa since 2005, implied last month that it would welcome him to America “as it has every democratically elected leader of India”. By behaving inconveniently, the Indian electorate is forcing Modi’s critics at home and abroad to take stock and readjust.

Guardian News and Media Ltd.