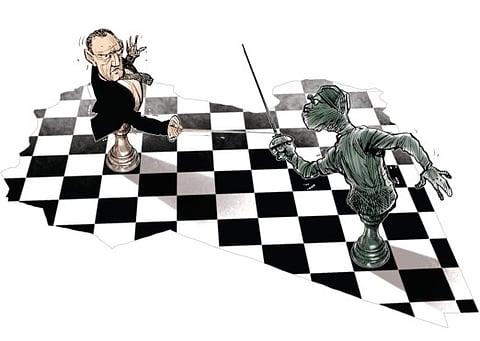

Libya is a chessboard for proxy wars

Daesh and Al Qaida thrive in the chaos and security vacuum left by the absence of a central government

Thursday brought us the third anniversary of the ‘liberation of Libya’, but there were few celebrations across a nation which has been mired in blood since the revolution, torn apart by endless fighting between rival armed militias.

Muammar Gaddafi was actually executed by the armed rebels on October 20, 2011 in a manner that was barbaric, even by the new standards set by Daesh (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant). Gaddafi’s body was displayed in a container of vegetables for three days until it rotted and stank. This putrefaction marked the true ‘liberation of Libya’ according to Mustafa Abdul Jalil, then head of the National Transitional Council (NTC), as he addressed jubilant crowds in Benghazi, the cradle of the revolution. Jalil also announced that the NTC would ‘embrace Sharia’ as the basis for the new Libya’s legal system. He quickly forgot that he had been a judge for 29 years and Justice Minister for four years under Gaddafi’s secular regime.

In the city of Benghazi, where Nato warplanes intervened to prevent the massacre of its citizens by Gaddafi in 2011, instead of songs, and drums and dancing to mark the third anniversary of the tyrant’s death, only the sounds of explosions and gunfire could be heard as heavy fighting between the Islamist Ansar Al Sharia and the self-titled ‘National Army’ led by renegade General Khalifa Haftar entered its ninth day.

An estimated 30,000 Libyans were killed during the revolution to unseat Gaddafi but almost as many — 25,000 —have died as a result of the civil conflict, power struggles and general chaos that has ensued.

And these deaths are in addition to the total collapse of the state and its institutions, rampant corruption, lack of basic services and the migration of one-third of the Libyan people to seek safety in neighbouring countries such as Egypt and Tunisia. Those nations who contributed their airplanes and ‘military advisors’ to the effort to unseat Gaddafi promised that ‘liberated’ Libya would become a regional oasis of stability and cohesion. Some even predicted, wildly, that Libya would become the next Dubai, a model of economic prosperity and good living. Not one of these dreamers travelled to Tripoli to celebrate this third anniversary of their great achievement.

Nor did they send congratulatory telegrams to the Libyan government... for where should they send them? Since August there have been two Libyan Governments and two parliaments after Islamists seized Tripoli and set up their own cabinet, under ‘Prime Minister’ Omar Al Hasi. The Islamists claimed that June’s elections, which returned the interim Prime Minister, Abdullah Al Thinni, were rigged. Al Thinni and his cabinet were forced to flee the capital, heading east, first to Bayda and then to Tobruk where they are now based. The prime minister’s seat has been the most popular in this recent round of musical chairs, with Al Thinni taking it while still warm from Ali Zeidan (who was dismissed by Congress in March 2014), vacating it when he ‘resigned’ in August and then getting back on (a new one) in September when he was ‘re-appointed’ in Tobruk.

Dangers faced by journalists

There is no state security apparatus and no regular army to speak of in Libya. Nobody knows what is going on, and the last people to try to speak out are the country’s journalists. The international NGO, Reporters Without Borders launched a campaign, also on Thursday, called ‘Not Seeing News From Libya Any More?’ to highlight just how dangerous it has become to be a media professional in the country. Its statement read ‘Since the end of the Libyan revolution, Reporters Without Borders has registered seven murders, 37 abductions and 127 physical attacks or acts of harassment targeting journalists. Libya was ranked 137th out of 180 countries in the 2014 Reporters Without Borders press freedom index, six places lower than in 2013’.

Al Thinni had a tri-partite meeting in Malta last week with his counterpart, Joseph Muscat, and Bernardino Leon, the head of the UN Support Mission to Libya. Al Thinni was seeking ‘international logistical support’ (a euphemism for a further Nato intervention, this time against the Islamists) but none seems to be forthcoming; nor have we seen Monsieur Bernard-Henri Levy, philosopher of the uprising, wandering the streets of Benghazi as he did when he was following the development of the revolution; Levy was able to persuade his friend former French president Nicolas Sarkozy to nudge western and Arab allies to intervene militarily in Libya then, but we do not see him on the phone to President Francois Hollande.

AFP reported last week that, in the light of ongoing anarchy, violence, tribal and ideological conflict, and widespread insecurity, some Libyans are even nostalgic for the days of Gaddafi.

I remember how bitterly I was castigated when I wrote a 2011 article in Al Quds Al Arabi warning against the Nato intervention. My argument was not because I supported the regime, but for fear of the disastrous unintended consequences. I warned that Libya would become another failed state like Somalia, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Libya has become a chess board for proxy wars between rival regional powers lining up behind the Islamic groups (under the Libyan Shield Force umbrella) or American ally, Gen Haftar. But it is the new kid on the block in Libya who is the most dangerous. There is a growing Daesh presence in the east of the country and in Derna, the Shura Council of Islamic Youth (MSSI) pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi earlier this month and installed a Yemeni emir called Abu Taleb Al Jazarawey. Daesh have established a Sharia court in the city and its flags are now commonplace.

Daesh and its close relative, Al Qaida, thrive in the chaos and security vacuum left by the absence of an effective central government. Today’s Libya, as it enters its fourth post-revolutionary year, offers the perfect climate.

Abdel Bari Atwan is the editor-in-chief of digital newspaper Rai alYoum: http://www.raialyoum.com. You can follow him on Twitter at www.twitter.com/@abdelbariatwan.