Japan: Equality or estrangement?

In Abe’s view Japan needs to regain, wherever possible, the right of independent decision-making

Those whom the gods would destroy, they grant their wishes. Will that bit of ancient wisdom now hold for the United States and Japan?

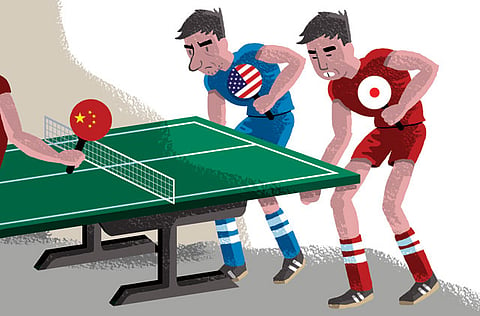

For a half-century, the US, which wrote Japan’s postwar “peace” constitution, has pressed the Japanese to play a greater role in maintaining Asian and global stability. But now that Japan finally has a leader who agrees, the US is getting nervous, with Secretary of State John Kerry supposedly calling Japan under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe “unpredictable.”

These strains in the US-Japan relationship – surely the foundation stone of Asian stability – first became noticeable in December, when Abe visited the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, which houses the “souls” of (among others) Class A war criminals from the Pacific War. The US has always criticised Japanese officials’ visits to the shrine, but through diplomatic channels. This time, America voiced its displeasure openly.

The US is rightly concerned about the negative impact of such pilgrimages on Japan’s relations with its neighbours, particularly China and South Korea. But the harsh tone publicly adopted by President Barack Obama’s administration raised serious concerns among some in Abe’s government who question Obama’s commitment to the alliance and suspect that he was using the Yasukuni issue as a pretext to signal a weakening of America’s defence commitment.

Such suspicions were sharpened after China declared its new Air Defence Identification Zone, which overlaps Japanese sovereign territory. The US tried to have it both ways: though the Obama administration sent US bombers through the new ADIZ to demonstrate its refusal to recognise China’s move, it also told US commercial airliners to acknowledge the zone and report their flight plans to the Chinese authorities.

Likewise, US acquiescence in China’s de facto ouster of the Philippines from the Scarborough Shoal (a disputed outcropping in the South China Sea) raised questions in Japan about the two countries’ supposed harmony of interests. In fact, although the US extols the virtues of its partnership with Japan, successive American presidents have been vague about the details. Ultimately, the idea always seemed to be that Japan would pay more for defence, but the US would set the partnership’s objectives.

Abe’s conception of the US-Japan partnership presupposes much greater equality. After all, a society like Japan, trying to escape two decades of economic malaise, cannot feel completely comfortable outsourcing its national-security strategy, even to an ally that is as respected and reliable as the US.

Far from being based on chest-thumping nationalism, Abe’s national-security strategy reflects, above all, a deep awareness of how a lost generation of economic growth has affected the Japanese. His bravura diplomatic performances sometimes give the impression that a self-confident Japan has been a normal feature of the global landscape. Strangely, it is all but forgotten – particularly by the Chinese – that for two decades Japan has watched China’s rise quietly from the sidelines (even supportively, to the extent that Japanese investors have poured in billions of dollars in the three decades since Deng Xiaoping opened the economy).

Indeed, Abe has succeeded so well in returning Japan to the world stage that his US and Asian critics act as if the only problem now is to moderate Japanese self-confidence – a notion that would have been laughable just two years ago. But the fact remains that one of Abe’s primary worries is the spiritual malaise that accompanied Japan’s long economic stagnation. Those who see in his patriotic rhetoric a desire to whitewash history miss his real concern: economic revival is meaningless if it does not secure Japan’s position as a leading Asian power.

The US, however, regards Abe’s worries about Japan’s spirit as peripheral to its efforts to forge a lasting relationship with China and overhaul its strategic presence in the Pacific. For example, the US views the Trans-Pacific Partnership – the huge trade agreement involving it, Japan, and 10 other leading Pacific Rim countries – as a technical scheme that will bring economic benefits through greater trade. But, for Abe, the TPP’s value for Japan’s sense of identity – that it is now a more outward-looking nation – is just as important.

In Abe’s view, Japan needs to regain, wherever possible, the right of independent decision-making if it is to manage successfully the challenge posed to it by China. This does not mean that Abe’s Japan will become an ally like France under Jacques Chirac, spurning US leadership for the sake of it; instead, Abe seeks a policy of cooperation with the US that reflects voluntary nature. He believes that, given the new balance of power in Asia, the alliance will be meaningful only if each partner has a real choice, and the wherewithal, to act autonomously or with regional allies.

Fortunately, Japanese and American analyses of Chinese trends are not very different. Both generally view China as having embarked on a probing strategy in search of weak spots where it can expand its geopolitical reach. And both believe that only when China is convinced that such probes will yield no lasting benefit can serious negotiations about a comprehensive security structure for Asia take place.

But even here, there is a difference. The US, convinced of the importance of intentions in the conduct of foreign policy, believes that once China recognises the limits to its power, a structure of peace will follow naturally. Abe, by contrast, believes that only a favourable balance of power can be relied upon, and he is determined that Japan play its part in constructing that balance.

Although Abe has lifted Japan’s sights and self-confidence, he recognises that Japan faces real limits. The US, too, should recognise that there are limits to the extent of the subordination that it can ask of an ally. Some wishes really are better left unfulfilled.

Project Syndicate, 2014.

Yuriko Koike, Japan’s former defence minister and national security adviser, was Chairwoman of Japan’s Liberal Democrat Party and currently is a member of the National Diet.