In 1976, then US secretary of state Dr Henry Kissinger produced a list of countries his administration accused of sponsoring international terrorism. For obvious reasons, the list included Cuba and North Korea, alongside three Arab countries: Syria, Iraq and Libya. Iran was added after the Islamic revolution and Sudan joined the club following the 1989 military coup.

But because the concept of terrorism is elusive and extremely difficult to define, it means different things to different parties. Hence, the list remained exclusively American, reflecting the national interests of the US, rather than becoming something universally accepted. In pursuit of more consensus and to make the list internationally acceptable, Dr Martin Indyk, special adviser to president Bill Clinton on the Middle East and former ambassador to Israel, suggested in the early 1990s a new term to describe these countries: rogue states. Although defining a rogue state was much easier than defining terrorism, the new concept created more problems than it solved.

Most political analysts describe a state as rogue when it does not abide by international laws, violates the UN Charter and uses force or the threat of force to maximise its gains in the international arena. According to this definition, most countries are rogue states because they behave this way when they deem it necessary. In the absence of an overarching, universal authority, the international system is an environment in which states must do whatever it takes to maintain security, sometimes through violating the law. This assumption is based on the fact that all states exhibit similar foreign policy behaviour despite their different political systems and that the structure of the international system makes them act the way they do.

Yet, although states are functionally similar, they differ greatly in their cap-abilities. States may be alike in terms of the challenges they face, but different in their abilities to perform them. The capacity of states to pursue and achieve their objectives varies according to where they are placed in the international system and, even more fundamentally, their relative power. In this context, states, like individuals, break the law to different degrees depending on the power they have and whether it allows them to do so with impunity. Weak states are, therefore, limited in how much freedom they have to act outside the law. They are usually constrained by the forces of the international system, which is dominated by the great powers. Hence, when Saddam Hussain invaded Kuwait in 1990, the international community — led by the US — punished him. But when the US invaded Iraq in 2003, it got away with it. The different responses to similar actions are explained by the power differential between the two countries.

Lust for power

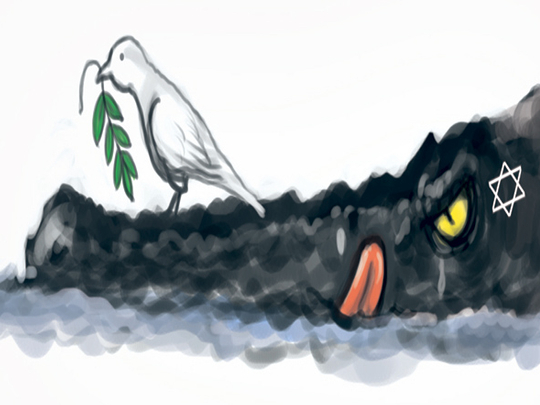

In an archaic system, weak or small states may break the law in pursuit of their own survival, but powerful ones do so in pursuit of universal or regional domination. Here, strong states conduct their policies with complete disregard for international law and conventions and, hence, are considered to be ‘rogue' in nature. The only regional state that deserves this title is Israel. It defies international laws and violates the UN Charter, not out of security requirements, but in pursuit of supremacy and material gains. It occupies foreign lands, violates the rights of populations under occupation and uses excessive force to subjugate them. It steals the national resources of the Palestinians — water and fertile lands — and makes the lives of powerless civilians miserable.

Furthermore, while the countries listed by Washington as rogue states are considered so in the light of the national interest of the US, in the court of international public opinion things do not look quite the same. Recent surveys in many parts of the world have shown increasing unease with Israel and its policies. In Europe, for example, increasing numbers of Europeans think that Israel — and not Iran, Libya or Syria — is the major threat to international peace and security.

Gone are the days when Israel was regarded by most of the western world as a victim, trying to survive in a hostile Arab environment. Israel's defiance of the international community and its resistance to US efforts to revive the Middle East peace process have confirmed its status as an outlaw. The apparent Israeli assassination of Hamas commander Mahmoud Al Mabhouh in the United Arab Emirates in January has made this fact all too clear. The killing of Al Mabhouh triggered a wave of international outrage over the use of fraudulent passports by the assassins and earned Israel the title of ‘the world's true rogue state'.

Dr Marwan Al Kabalan is a lecturer in media and international relations at Damascus University's Faculty of Political Science and Media in Syria.