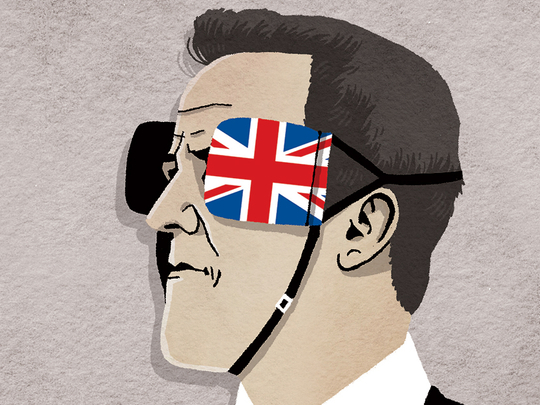

From the moment he took office, commentators said that David Cameron “looked like a prime minister”. However, deferential their assumption that old Etonians were born to rule, they were right to concentrate on appearances. Cameron speaks his lines and plays his part. He is a lead rather than a leader. Britain’s ‘acting’ prime minister.

Like a body double, his administration fills the roles history assigned it. Britain remains one of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. It still has the second strongest military force in Nato and the third largest economy in the European Union (EU).

Yet, as far as a convulsed Europe is concerned, Britain might as well not exist. No one worries what Cameron thinks. No one turns to him for support, let alone solutions. Twentieth-century Conservatives once boasted that they and they alone protected national security. There is no better gauge of political journalists’ servile treatment of Cameron than that so few show how this dilettante from the PR industry does not know how to respond to the national security crises of the 21st century.

Britain’s politicians stand by while Brussels, the International Monetary Fund and Berlin impose the economic policies of the 1930s on southern Europe and then blink with surprise when they get the extremist politics of the 1930s in return. The rolling Eurozone crisis threatens Britain’s prosperity and more. It isn’t inconceivable that Greece, driven beyond endurance by the destruction of its economy, could leave Nato and ally with Putin.

It is not inconceivable that Marine Le Pen could be the next president of France. Her government would be in Russia’s debt, literally so, as the Kremlin is bankrolling her. It is not inconceivable that members of France’s ethnic minorities will start emigrating to Britain. Indeed, Greek, Spanish and Portuguese refugees from the Eurozone are already there. When you look at Europe’s balance of power and movements of peoples, the most disconcerting feature of 2015 is that what was once inconceivable has become all too conceivable.

Where are the British government’s initiatives to deal with these new threats? What are Cameron’s aims in Europe and how does he intend to achieve them? Answer comes: There are none, because this is a show government, not the real thing.

Speaking of Putin, Russia annexes Crimea, turns Ukraine into Bosnia and threatens to test Nato unity by unleashing proxy forces in the Baltic states. Once again the questions pile up. Where does Britain stand? How does it intend to contain and deter the Kremlin? If our leaders have answers — and I am not sure they have — their opinions mattered so little that no one bothered to invite Britain to the Minsk talks last week.

There’s an old line about Israel that it has no foreign policy, only a domestic policy. The same applies to Cameron’s Britain. Cameron sold himself as a centrist conservative. When United Kingdom Independence Party (Ukip) and his own Right wing rose up against him, he ought to have shown the political courage that German Chancellor Angela Merkel showed when she faced down the anti-Muslim protesters in Dresden. But Cameron did not stand on principle. He jumped from this focus group to that next news cycle and tried to please his mob by outflanking Nigel Farage on the right.

His domestic policy became his foreign policy. He alienated Poland, our strongest European ally, and drove naturally conservative Polish immigrants away from the Tories with his attacks on freedom of movement. “He’s f***** up,” said the Polish Foreign Minister, Radoslaw Sikorski, in a secretly taped conversation of bracing frankness. He should have told the right to “f*** off, tried to convince people and isolated [the sceptics]. But he ceded the field to those that are now embarrassing him”.

None more so than Philip Hammond, Cameron’s Foreign Secretary. Under Tory stewardship, the Foreign Office’s Eastern Europe and Central Asia Directorate, which covers the old Soviet empire, became a shambles. Ministers left the post of director vacant and the department leaderless. What diplomats remained were told to concentrate on expanding trade rather than focusing on the evidence that Russia was an imperialist power on the march. Britain does not have a Russian policy. Hammond will not say whether or not Britain should go beyond sending lethal equipment and arm the Ukrainian government forces. He told the Commons: “The UK is not planning to do so,” which seemed clear enough. But, he continued, “we could not allow the Ukrainian armed forces to collapse”.

As Ian Bond of the Centre of European Reform told me, this is not a strategy, it is just noise. You either arm Ukraine or you do not. If you wait until its armed forces are on the point of collapse, it will be too late. But Hammond cannot have a Russian policy, because that would involve cooperation with European allies he and his party would rather die than help.

As with Russia, so with the EU. A Tory party whose supporters want to leave, and a Tory leadership, which does not dare take them on, cannot play the role of candid friend and urge Europe to break out of the euro disaster, when most Europeans do not think it a friend of any kind.

You would never guess it, but George Osborne has a euro policy buried somewhere in the Treasury. Of the two ways of dealing with a failed currency, he prefers the Eurozone should integrate and the north take on the south’s debts to the alternative of euro countries returning to national currencies. But Osborne does not urge Germany to boost demand, endure greater quantitative easing and accept a fiscal union. He cannot. In Right-wing circles, an attempt to save the EU from itself, even an attempt the Germans rejected, would be seen as a kind of treason. The British right does not want to save the EU. It wants it to fail, whatever the consequences for Britain.

I cannot hate this government as some of my younger colleagues do. You cannot truly hate a political movement unless it settles big issues and offers no hope of reopening them. The Cameron administration has settled nothing. At home, it has not removed the deficit or rebalanced the economy. It has not even built a new London airport or replaced decrepit power stations. Abroad, it mouths vacant phrases as Europe crashes around it; words so vacuous they are forgotten as soon as they are uttered.

Cameron’s government is a stop-gap government. It fills the time, but doesn’t change the scenery. Cheer up. In less than three months, Britons will be able to change the scenery by chucking it out.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd