Is assassinating terror suspects lawful?

US making a mockery of justice by pressing for the killing of a citizen living in Yemen

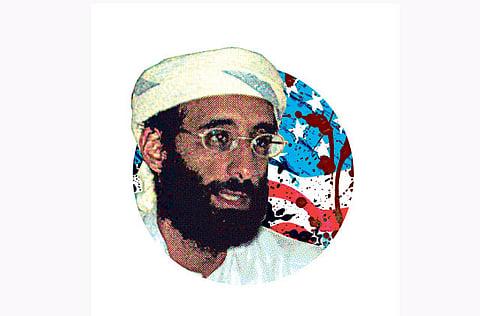

Last month, civil liberties groups and the family of cleric Anwar Al Awlaki filed suit to stop the US government from killing Awlaki — an American citizen living abroad in Yemen.

The US, which is trying to have the case dismissed, labels Awlaki a threat for his alleged involvement in terror plots and inspiring anti-American sentiment. Awlaki is believed to be a target for extrajudicial killing.

The suit raises a fundamental question: When, if ever, is it lawful for governments to assassinate? While a private individual has no right to kill except in self-defence, the right of those acting under colour of law, such as police officers, soldiers, or the CIA, is considerably more complex. Even a soldier in a declared war does not have an unfettered right to kill the enemy.

At the close of the Second World War, when the question arose of what to do with Nazi leaders, then British prime minister Winston Churchill proposed shooting them. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin agreed, but the US advocated a trial.

It argued, and eventually persuaded, both the British and Soviet governments that the proper path was not blind retaliation, but the rule of law. A lawful procedure required a finding of individual guilt before punishment could be implemented.

The US argued that leaders of the German and Japanese government and military should be tried in a court of law for having waged an aggressive war and for crimes against humanity. Only if they were found guilty after a trial, at which they would have the right to defend themselves and present evidence, could they be punished.

The US position prevailed, and the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials set an historic post-war gold standard for what came to be called the movement for the rule of law. The core doctrine is that government itself must obey the law on the same basis as individuals.

The doctrine has been embraced by every US administration since 1945, but America has had difficulty adhering to it.

Twenty-five years after the Nuremberg trials, the CIA sought to assassinate Cuban leader Fidel Castro. This breach was mended in 1976 when US president Gerald Ford signed an Executive Order forbidding any government employee from engaging in assassination.

That policy lasted until 2002 when president George W. Bush told the CIA to assassinate terrorist leaders whose names were on a ‘high value target list'. How one got either on or off the list was never made clear.

By allegedly authorising Awlaki's assassination, an American citizen living in Yemen, the US administration shows that American policy has not yet returned to the Nuremberg standard.

Right way

The key fact in the administration's decision seems to be that Awlaki resides in Yemen. If the citizen resided in Chicago, the administration would not be suggesting that he be assassinated. He would be arrested, charged, tried, and if found guilty, sentenced, and imprisoned.

Extrajudicial killing may meet mafia standards, but it does not meet the due process requirements of the US Constitution's Fifth Amendment or the Sixth Amendment's right to a jury trial and to confront witnesses. It is deeply troubling that the US government claims the right to kill anyone.

That a government has the right to kill in certain defined circumstances cannot reasonably be denied, but it must be to protect itself or its citizens from imminent danger, and the protective measures must be proportionate to the nature of the danger. In Awlaki's case, an American citizen hiding in the chaotic state of Yemen poses no direct threat to the existence of the US government.

The troubling aspect of extrajudicial killings is that the executive branch acts as prosecutor, judge, and executioner. While officials claim that an American in Yemen is advocating and perhaps participating in terrorist acts, they disclose no evidence. No independent party judges whether there is sufficient proof to justify killing.

Indeed, the plaintiffs in the Awlaki suit demand that the US government make transparent the process used to determine whether a citizen can be executed without trial. When a government asserts an unreviewable power to kill its own citizens, it mocks the rule of law, and claims a power more familiar to tyrants than democracies.

Ronald Sokol is a lawyer in France. He taught at the University of Virginia Law School and is the author of Justice after Darwin.