India continues to remain a soft state

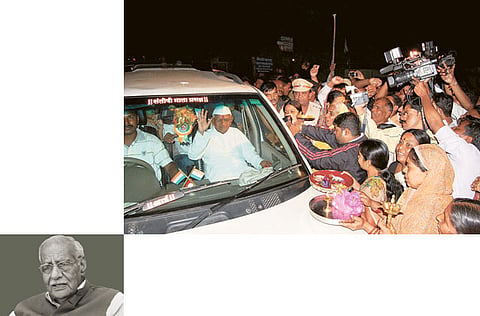

The Hazare movement against corruption had the stirrings of a revolution. It could have ushered in change sought by the common man

In the fifties and the sixties, India was known to be a soft state.The allegation was that it could not take hard decisions because of "unfavourable environment in attitudes, cultures and institutions."

The entire Anna Hazare phenomenon shows that we continue to be a soft state.

On the 12th day of the fast, both the government and activist Hazare, along with his team, were bending backwards to have parliament pass a resolution so that the fast would end by that afternoon. The government's stand only 24 hours earlier was that no resolution was possible but a discussion could be accommodated "under some rule."

Hazare's side was adamant that the anti-corruption Ombudsman (Lokpal) Bill must be passed before he could break the fast. He himself did not insist on having his version of the bill passed, but surprisingly wanted only a resolution enunciating his demands.

Some say it happened that way because Federal Minister Vilasrao Deskmukh, who knew Hazare personally, went straight to him with Prime Minister Manmohan Singh's assurance on the resolution. This was how the "stumbling block" that Hazare's team had become was bypassed. Many insiders maintain what weighed with Hazare was the unanimous appeal by parliament to break the fast. Yet it turns out that Hazare wanted only to see that Parliament would take up the Lokpal Bill, even if it was not his version.

Illusion of victory

The fact is that the members of civil society had lost stamina. I heard in many drawing rooms that they had enough of Hazare and wanted to "hear something else." That was expected from a soft state. Over the years, I have felt that the society was willing to strike but afraid to wound. By temperament, we do not join issue. If ever it comes to that, we try to find a compromise which would be nearer to our demand or gives us an illusion of winning. The truth is that we do not allow things to reach a boiling point because we are not prepared to face the consequences.

True, we are not radicals. Nor do we favour changing the status quo. Yet this time the movement had stirrings of a revolution. It could have achieved something in the shape of parivartan (change). Whether the system delivered or not was not an issue for the fast. The issue was that people were expecting something that would change their life.

Still there is no running away from the fact that the Hazare movement against corruption had galvanised the middle class youth for the first time since Gandhian Jayaprakash Narayan's call for a change in 1974. Yet both the movements did not allow the people's anger and anguish to concretise and saw to it that they did not go beyond ‘control.' Had the JP movement lasted longer, the nation would have steeled itself to fight against the undesirable elements, parading themselves as votaries of change but perpetuating the status quo. They were the beneficiaries and falsified JP's dreams. In Hazare's case, the disconcerting part was the fast. Otherwise, his movement would have ushered in a revolutionary era, the dawning of the second independence. I wish Hazare had separated the movement from the fast.

That parliament is supreme. People elect its members. Yet what should not be forgotten is that they continue to be supreme even when they demand circumventing of an institution like the Standing Committee of parliament discussing the Lokpal bill.

The constitution says: "We, the people…" Therefore, their assertion should not be an affront to parliament or state legislatures. This is only a reminder to the elected representatives that the sovereignty lies with the people. The Lokpal bill or other steps have to ensure that. The right to recall may not be an ideal way but it at least keeps the sword of public sanction hanging over the head of the elected.

I was amused by actor Om Puri's argument that a parliament member must be literate. India has been served well by the earlier Lok Sabhas (Lower House) which had at least one fourth of 545 members illiterate. Dr Rajendra Prasad, chairman of the Constituent Assembly, wanted to have a provision to lay down the minimum educational qualification for legislators. India's first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, opposed the proposal. His argument was that when they were engaged in freedom struggle, the illiterate and the backward were the ones who followed them while the literate were toadies, on the side of the British rulers.

Hazare's movement has been supported as much by the illiterate as the literate. The effort should be to make everyone literate, not to punish the illiterate who have had no opportunity to go to school.

What does not come under the ambit of Lokpal is poverty. Electoral reforms are essential so that the right type of people reach the Lok Sabha and the state legislatures. Yet more important are the measures to enable the have-nots to become the haves. Like corruption, poverty in India is indelible. There are no soft options.

Kuldip Nayar is a former Indian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom and a former Rajya Sabha member.