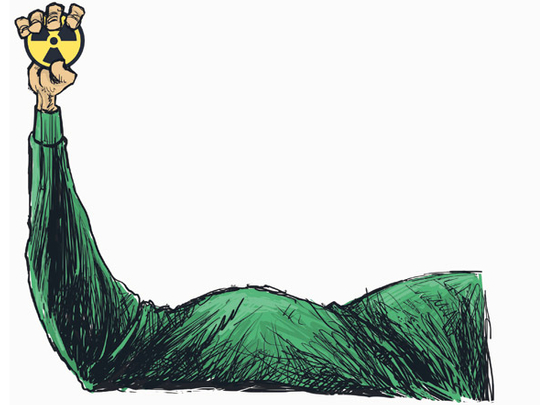

Iran's announcement that it has already enriched uranium to close to 20 per cent, under the supervision of the International Atomic Energy Agency, to produce radioisotopes for its medical reactor in Tehran has triggered a fresh outbreak of hysteria. There have been renewed calls for sanctions to force it to close down its nuclear programme.

But the more Iran is threatened, the more defiant it becomes — and the more remote the chance of an agreement. The latest quarrel seems to be about the quantity of low-enriched uranium Iran is ready to swap with Russia and France in exchange for nuclear fuel rods for medical purposes — rods that cannot be used to make weapons.

As Iran is deeply suspicious of western intentions, it has proposed sending its uranium abroad in batches. But its western interlocutors want it to surrender the bulk of its uranium supplies all at once — some 1,200 kilograms — so as to preclude any possibility of enrichment to weapons-grade levels.

Iran's Foreign Minister Manouchehr Mottaki held talks last week with Yukiya Amano, the new Japanese IAEA chief, who replaced the Egyptian Mohammad Al Baradei. Mottaki described the talks as "very good", while a more sceptical Amano called for an "accelerated" dialogue.

Two rival coalitions now confront each other on the international scene: the first wants to impose harsher sanction on Iran and, if sanctions prove ineffective, to bomb its nuclear facilities; the second recommends a patient dialogue with Tehran, and nothing but dialogue.

Somewhere between the two — and uneasily holding the ring between them — is US President Barack Obama. His early policy of engagement with Iran has hardened into something like impatient opposition to the Islamic regime, and even into a reluctant acceptance that tougher sanctions may be necessary. This is a serious blow to his policy of reaching out to the Arab and Muslim world.

Israel and its hard-line friends in the United States are prominent in the first coalition. They have long campaigned for resolute action against Iran — as they did for the overthrow of Saddam Hussain in the 1990s. Their claim is that an Iranian bomb would pose an ‘existential' threat to Israel as well as a global menace. "We must recruit the whole world to fight [Iranian President Mahmoud] Ahmadinejad," President Shimon Peres declared recently, echoing the bellicose tone Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu adopts whenever he refers to Iran.

The coalition advocating dialogue with Tehran includes China, Turkey, Brazil, and — with more or less unanimity — Iran's Arab neighbours. Arab states have no wish to see a nuclear-capable Iran, but they are far more frightened of an Iranian-Israeli war, which could have devastating consequences for the security and stability of the region and for Arab oil exports.

China, Iran's leading trading partner, is opposed to sanctions and seems ready to veto any move at the Security Council to impose them.

Arab League Secretary General Amr Moussa has urged the Arabs to take the initiative in talking to Iran, with the aim of drawing it into some sort of regional security arrangement. The idea is gaining some ground in Arab circles.

Contest set to sharpen

As Iran presses ahead with uranium enrichment — as it has the right to do for peaceful purposes under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty — the contest between the two coalitions is likely to sharpen. On balance, however, the scales are tilted against punishing Iran more than it is already being punished. Obama may agree to some tightening of the sanctions regime — in Paris this week his Defence Secretary Robert Gates said "the only path that is left to us ... is the pressure track" — but he has by no means joined those hawks who blatantly recommend bombing Iran. Indeed, Obama is widely believed to have warned Israel that an attack on Iran would damage US interests.

Obama's pro-Israeli critics have accused him of "appeasement". At last week's Munich security conference, US Senator Joe Lieberman, chairman of the Senate committee on homeland security, declared: "We have a choice here: to go to tough economic sanctions to make diplomacy work or we will face the prospect of military action against Iran." "A nuclear-armed Iran," he added, "would provoke chaos in the Middle East, send world oil prices soaring and end any hope of a peaceful solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict."

These predictions would seem to be entirely mistaken. Far from provoking chaos, an Iranian bomb could stabilise the region and curb Israel's aggressive behaviour towards its neighbours — something the Arabs have not managed to achieve in the past six decades. Indeed, by creating a balance of power with Israel, and thereby limiting its freedom of action, Iran might actually encourage Israel to make peace with its neighbours, including the Palestinians. The only development that would send oil prices soaring is an Israeli attack on Iran.

All the indications are that the debate about what to do about Iran will continue without either side landing a decisive blow. It may be that events inside Iran will bring matters to a head. Yesterday, February 11, was the anniversary of the 1979 revolution. The whole world was watching to see whether anti-government protests would manage to affect the future policies of the Islamic Republic.

Patrick Seale is a commentator and author of several books on Middle East affairs.