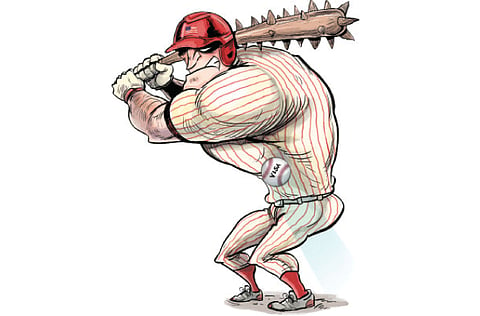

How Washington plays hardball with visa rules

America’s decision sets up a potential clash with UN

Hamid Aboutalebi, Iran’s choice as its next Ambassador to the United Nations, has freely admitted that he served as a translator for the student group that in 1979 stormed the US embassy in Tehran and sparked a 444-day-long hostage crisis. In the eyes of Texas Senator Ted Cruz, that makes Aboutalebi a terrorist and an unfit choice to represent Iran at Turtle Bay. Last week, the White House announced that it agreed with Cruz and said that it would deny Aboutalebi a visa to the US, making him the first UN ambassador to be rejected by the US.

Calling his selection by Iran “not viable” and “extremely troubling,” Press Secretary Jay Carney had hinted earlier in the week that the White House may ban Aboutalebi from entering the US. But if the White House hoped to avoid a confrontation with Iran amid sensitive talks on the country’s nuclear programme, pressure on Capitol Hill made a clash over Aboutalebi all but inevitable. Last Thursday, the House of Representatives approved a measure already passed in the Senate that would deny a visa to any UN ambassador found to have engaged in terrorist activity against the US. “We concur with the Congress and share the intent of the bill,” Carney said, adding that the White House had informed both Iran and the UN of its decision.

In a statement to reporters, Hamid Babaei, a spokesperson for the Iranian mission to the UN, criticised the move. “It is a regrettable decision by the US administration, which is in contravention of international law, the obligation of the host country and the inherent right of sovereign member states to designate their representatives to the United Nations,” he said. The decision to ban Aboutalebi from taking up his post in New York comes on the heels of talks in Vienna between Tehran and western powers aimed at reaching a final agreement to curtail Iran’s nuclear programme. Following those talks, negotiators said that “intensive work will be required to overcome the differences, which naturally still exist at this stage in the process”. Speaking to reporters last week, State Department spokeswoman Jen Psaki insisted that the move to bar Aboutalebi would not affect those negotiations.

The decision sets up a potential clash with the UN, whose 1947 agreement with the US governing the body’s New York headquarters clearly forbids Washington from prohibiting the entry of UN ambassadors. “The federal, state or local authorities of the US shall not impose any impediments to transit to or from the headquarters district of representatives of Members,” the agreement reads. Under the terms of that agreement, disputes between the US and the body are to be settled through arbitration. Stephane Dujarric, the chief spokesperson for UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, declined to comment on the White House’s decision.

Though the US has previously attempted to bar the participation of certain groups at the UN, this is the first time Washington has prevented a UN ambassador from taking up his position, according to Julian Ku, a law professor at Hofstra University and an expert on international law. In 1988, the US had barred Yasser Arafat, the chairman of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO), from addressing the UN General Assembly. In response, the UN temporarily relocated its proceedings to Geneva. A year earlier, Congress had attempted to force the PLO to close its offices at UN headquarters, an effort that ultimately failed.

In approving the agreement, Congress added a provision stating that nothing in the text would limit the US’ ability to preserve its national security. That addendum has never been formally accepted by the UN and the US has rarely invoked the clause. “Up until now, the US has hesitated to use it. Even with regard to the PLO in earlier years, the US government and courts have resisted clamping down on their ability to come to New York City,” Kal Raustiala, a law professor at UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles). “So this is a big deal and a definite stretch of the intent of the Headquarters Agreement.”

According to Edward Luck, a historian and a former special adviser to Ban, it is unclear whether the national security provision can be applied to Aboutalebi. “There has to be some manifest reason and clear evidence of someone” posing a threat to US national security, and “it’s not clear in this case whether there is evidence,” Luck said.

For years, Iran and other countries hostile to the US have argued that Washington has abused its position as a host country and barred delegates from attending the UN by delaying the issuance of visas. Both Republican and Democratic administrations have denied those accusations, insisting instead that countries often wait until the last minute to register their applications. In a July 2009 US diplomatic cable released by WikiLeaks, US officials reported that an Iranian official named Alireza Salari Sharifabadi had requested for a visa to attend a conference on the global financial crisis the previous month. The US rejected the request, but only a month after the event had occurred. US “credibility is damaged when a visa is denied so long after the fact,” the cable stated.

A State Department cable attributed to Susan E. Rice, then the US ambassador to the UN, noted that US officials defended the decision before the UN’s Office of Legal Affairs (OLA), saying the visa “denial was made pursuant to the long-standing modus vivendi,” a practice that has been used to bar foreign diplomats suspected of engaging in activities that could threaten US national security. The UN generally “supports the modus vivendi and does not challenge us when we invoke it,” the cable stated. But “OLA was surprised that a decision to deny the visa was made almost a month after the end of the meeting that the applicant sought to attend. As the department is aware, OLA considers visa denials and delays a serious problem.”

When his diplomatic corps at the UN defected in February 2011, former Libyan strongman Muammar Gaddafi encountered visa complications when he tried to dispatch a top diplomat to New York to regain control of his diplomatic outpost. The official, Abdul Salam Ali Treki, who had previously served as the president of the General Assembly, was unable to get his visa approved in time to attend a critical debate on a Security Council resolution that authorised military action against Gaddafi. Eventually, the Libyan diplomat also defected, ending the discussion. Desperate, Gaddafi proposed sending a Nicaraguan diplomat, Miguel d’Escoto Brockman, who was already in the US on a tourist visa, to represent him. Libya’s former foreign minister, Mousa Kusa, claimed in a letter in March to Ban that he was forced to take this extraordinary move “given the impossibility of [Treki taking] upon its duties as the representative of the Jamahiriya [Libya] for not being given an entrance visa to the United States of America.”

But Rice questioned d’Escoto’s right to take up the Libyan seat at the United Nations, noting that Kusa had defected shortly after putting d’Escoto’s name forward and was no longer a member of the Libyan government. “The first question is whether he has actually been appointed in any legitimate fashion that anybody needs to consider at this stage,” Rice told reporters.

Rice also noted that d’Escoto had arrived in the US recently on a tourist visa. “A tourist visa does not allow you to represent any country, Nicaragua, Libya or any other at the United Nations,” she said. If he wished to serve as Libya’s representative, she said, d’Escoto would have to leave the US and apply for the appropriate visa. “If he purports to be or acts like a representative of a foreign government on a tourist visa, he will soon find that his visa status will be reviewed.”

— Washington Post