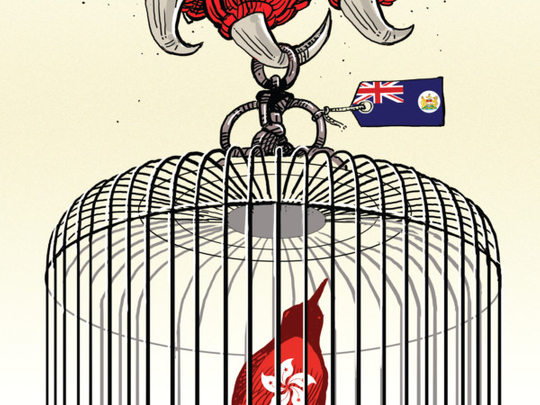

An old song made the rounds in Hong Kong as Second World War was ending and it went like this: ‘The fish will return to the ocean; The dog will have had his day; The hundred years are over; And the glory will fade away’. The song was predicting an end to British rule in Hong Kong, but reversion to China did not take place soon after the Communist Party ascended to power in the aftermath of the war. It was not because of British invincibility — Hong Kong had fallen to the Japanese land invasion in just 17 days in 1942 — but because the then-party chairman, Mao Zedong, did not wish for it to happen.

His precise reasons remain unknown, but starting a fight with a major western nation — even a declining one — that was not otherwise an antagonist could have impeded his consolidation of power. Nevertheless, from the founding of the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949, and onward, both Beijing and London knew that Britain remained Hong Kong’s colonial ruler only at China’s sufferance.

That understanding coloured everything that followed: Reluctance to create democratic institutions during colonial rule; a later, face-saving British push for Hong Kong’s democratisation; China’s deep and abiding suspicion of the same; and a resulting compromise — gradualism — that has hobbled the city’s governance. Hong Kong’s economy has prospered, but its government is hopelessly compromised and unable to solve local problems. When protesters began taking to the streets on September 26, eliciting a clumsy and violent government response, it was this gradualism without end, and not extremism, that was to blame. And it explains why China’s chance to truly re-integrate Hong Kong has already been lost for the foreseeable future.

It began in the aftermath of 1949, when Britain decided to avoid creating democratic institutions in Hong Kong lest China perceive this as securing a separate identity, or even independence, for the territory. It was received wisdom in Britain that at the first hint of democratic activity, China would demand a hasty return of the territory — a deeply embarrassing prospect for Britain with implications for its other colonial possessions. Ultimately, dismissing political activism worked out for all parties and Hong Kong came to be perceived as an apolitical city that an honest and professional civil service and a devotion to rule of law would suffice to keep calm. And it would be safe from the paroxysms of 1950s and 1960s Communist rule on the mainland.

However, everything changed as the end of Britain’s 99-year leasehold on the territory, slated for 1997, approached. The British pressed the Chinese for a decision on Hong Kong’s future and the two agreed to the Joint Declaration in 1984, which stipulated that Hong Kong would indeed revert to China in 1997. In other words: A liberal democracy agreed to cede its freewheeling, laissez-faire territory, against its will, to an authoritarian regime. This was a wake-up call to a heretofore quiescent population, alerting them that responsibility for fully sustaining Hong Kong’s identity and way of life would eventually sit on their shoulders alone. To be sure, the preponderance of Hong Kong people felt Chinese, and the legitimacy of colonialism had faded even there. But there was hardly any belief in the extant regime in China. As a result, after 1984 — gradually at first and intensively after the 1989 Tiananmen tragedy — Hong Kong dropped its apolitical veneer.

At the time of the Joint Declaration’s signing, China had wanted to supplant Britain gracefully. Having to exert sovereignty over an unhappy populace was not in China’s interest because it could harm Hong Kong’s position in the international economy. So China adopted the ‘one country, two systems’ concept, whereby Hong Kong’s political and economic freedoms were to be preserved for 50 years. Further, “Hong Kong people governing Hong Kong” was an expression put into the public domain by the Chinese leadership, an only slightly veiled swipe at colonial Britain, which for 150 years had sent a governor, a colonial secretary, finance secretary, police commissioner, top civil servants and military officers from Britain. Deng Xiaoping, China’s leader at the time, offered Hong Kong a great deal and in exchange all he asked was that tomorrow’s leaders be patriotic and love China.

Left unsaid and much debated in the years of negotiations leading up to the completion of the Joint Declaration — which sought to provide the overall architecture for Hong Kong’s future — was by what means, by what institutions and by which officials Hong Kong would be governed. China wanted nothing to be delineated in this regard. Britain knew better. Hong Kong wanted to know what kind of governance was on offer and, further, British diplomats and politicians understood that if a mention of future governance was omitted in the Joint Declaration, then the treaty might not be ratified by the British parliament. Britain, the weaker negotiating party unable to guarantee that China would never transgress the terms of the treaty — an abiding worry of the people of Hong Kong — shifted the debate to independent political institutions as a recourse.

After apparently acrimonious secret negotiations, on the eve of signing the Joint Declaration, China grudgingly accepted this language: “The legislature of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall be constituted by elections. The executive authorities shall abide by the law and shall be accountable to the legislature.” Within months, the Chinese leadership regretted the concession and relentlessly demanded that the British retreat from any further advocacy of democratic reform.

However, it was too late. A promise for Hong Kong’s democratic reform — at least for the remainder of British rule — formed the heart of the parliamentary debate and the record was clear that Britain had signed an agreement with China that allowed for participatory democracy. China saw this as an overt attempt by Britain to guarantee influence in Hong Kong in perpetuity, using liberal elected officials as proxies.

China’s suspicions deepened when the crackdown on student-led political protesters at Tiananmen Square sent shudders through Hong Kong, deepening and widening the city’s search for institutions that would set it apart from the mainland — an activist legislature with a democratic base being one attractive option. For the 13 years between the signing of the declaration and the handover, Chinese leaders struggled mightily to limit Britain’s promises. The handover, when it finally occurred in June of 1997, was not a convivial occasion.

To preserve the peace and prosperity that both nations relied upon to keep Hong Kong afloat, the two powers settled into an uneasy agreement to attenuate democratic progress. In other words, their solution was gradualism. This understanding was embodied in the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s constitution. It was agreed that Britain would never permit universal suffrage, while China would not fully reverse the complex array of direct and indirectly elected officials that Britain used to fill its legislature. Even the last governor, Chris Patten — who tried valiantly to expand the franchise for democratic participation — never proposed universal suffrage. He, too, lived within the terms of the deal. And notwithstanding China’s dismissal of the Patten-era legislature after the handover, Chinese authorities did eventually return Hong Kong to a mix of direct and indirect legislators. Still, no one made a move to ensure the accountability of the chief executive (successor to the colonial-era governor), notwithstanding the terms laid out in the Joint Declaration. The notion of gradualism was preserved by both sides and has endured for 17 years — but it is clearly fraying.

This approach has deadened good governance and it has soured Hong Kong, possibly the only entity in the world where the government is essentially appointed by an outside power, but the opposition is locally elected. The current system satisfies China’s insistence on control and predictability largely because it is a recipe for stasis. The economy hums while Hong Kong’s tycoons get rewarded for their close affiliation with Beijing’s leadership. But it also means Hong Kong’s society cannot count on its government to solve local problems. There is simply no mechanism for debate and compromise when part of the government answers to the electorate and the other part to China.

Because of the choices it has made, both before the Joint Declaration and since, there is one thing China will have difficulty achieving: The full and gratifying re-integration of Hong Kong. It was lost a century-and-a-half ago by a prostrate and embarrassed China — and it will remain lost, so long as Hong Kong’s government is everlastingly forced to break its promises and perpetuate an unsatisfying form of democracy based on unending gradualism. Hong Kong’s return to China in 1997 should have underscored China’s resurgence and confidence — as the notion of ‘one country, two systems’ was meant to showcase — but it has hardly been so. Instead, it has revealed Beijing’s insecurity and its propensity to attribute its troubles to foreigners who harbour designs on its financial centre.

Deng, in his day, had only asked that local leaders be patriots and love China. There is no evidence that democrats do not meet his criteria, but China still believes otherwise. Today’s demonstrators may fade away, but the resentment will persist. Those who can leave Hong Kong will take their money and talents abroad. And Chinese leaders will in time lead an increasingly angry people in the city, as its glory and its riches will be sacrificed.

— Washington Post

Dalena Wright is a fellow at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government.