The continuing wrangles over the movie Selma — contention over the relative roles played by Martin Luther King Jr, the civil rights movement, Lyndon Johnson and the federal government — miss the essential point: In the spring of 1965, the Selma demonstrators and the president of the United States forged an authentic partnership that ultimately resulted in the passage of the Voting Rights Act. The act guaranteed the right to vote to millions of African Americans. This historic landmark was realised because the pressure from the outside brought to bear on our ruling authorities was fully embraced by the government.

On March 7, 1965, a day forever known as ‘Bloody Sunday’, peaceful demonstrators were savagely attacked by local police on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The brutal images that flashed across the television screen provided a sense of urgency to the issue of voting rights. Eight days later, on March 15, I reached my White House office in the morning and learnt that I was to work on the speech President Johnson was to deliver that evening to a joint session of Congress, urging the immediate passage of the Voting Rights Act. There was no argument to be weighed in this speech. There was no debate, one side against the other. There was only one side and one position. This was a moral issue. It was a matter of simple justice.

While I may have helped with the words, it was the message the president wanted to send. The force of his embrace gave them their power. “At times, history and fate meet at a single time, in a single place, to shape a turning point in man’s unending search for freedom,” Johnson began. “So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama.”

“The real hero of this struggle,” the president made clear, “is the American Negro. His actions and protests, his courage to risk safety and even to risk his life, have awakened the conscience of this nation ... He has called upon us to make good the promise of America.”

The cause of civil rights must be our cause, he continued. “It’s all of us who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice ... and ... we ... shall ... overcome.”

After a moment’s silence, an electrical charge went through the room. In the well of the House, I tried to control my breathing. Later I heard that in Alabama King wept.

By summoning the anthem of the movement, LBJ embraced the rallying cry of thousands of young civil rights workers. The reaction signified the recognition that the president had placed the power of his office behind their struggle.

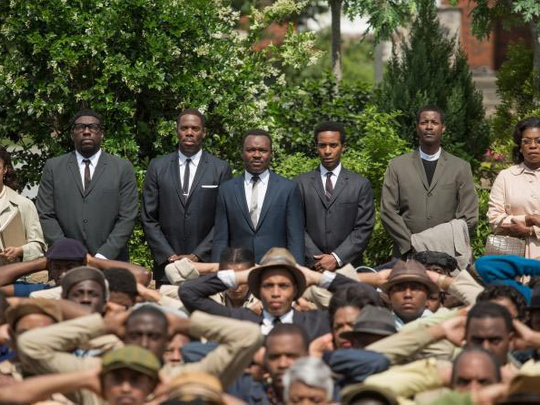

Playing out of a great drama

Before the eyes of the nation, a great drama was playing out. The moral imperative of a social movement had become the legal imperative of the government. In our democracy, there is tandem motion forward. Our government always lags behind an originating movement. The anti-slavery movement shaped the debate that led to the Republican Party, to the election of Abraham Lincoln and, eventually, to the Emancipation Proclamation.

The progressive movement created a passionate consensus that allowed Theodore Roosevelt to pressure Congress to confront the problems of the Industrial Revolution. The gay rights and women’s movements mobilised citizens, whose fight for justice led to ongoing legislative changes, civil unions and gay marriage.

So it was at Selma — the civil rights movement initiated the momentum that, together with the conviction and impassioned skill of President Johnson, led to one of the most important pieces of legislation in the 20th century. This is indisputable. I was lucky to be there, to witness Johnson at work during those months. I witnessed his fervour and determination to get it done.

Far from resisting King, he worked all the avenues of power to do something with all the might and matchless skill he could muster. The combination of Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement with Lyndon Johnson and the federal government created neither a black moment nor a white moment. It was an incandescent American moment.

— Washington Post

Credit: Richard N. Goodwin served as a special assistant and speech writer for President Lyndon Johnson.