Eye for an eye will not solve anything

Senseless army operations will only bring all the disgruntled elements together

Two days after Malala Yousufzai was shot in the head by militants from the Pakistani Taliban, I sat with her father outside the intensive care unit in Peshawar while she fought for her life. In a war in which there have been so many tragic things to come to terms with, seeing her lying there unconscious and gasping for breath was by far the most shocking. Her shooting went not only against the teachings of Islam, but also against Pashtun traditions, in which you would never think of hurting a woman — let alone a 14-year-old girl on her way home from school. As a father, naturally, I pictured one of my own children lying in that hospital.

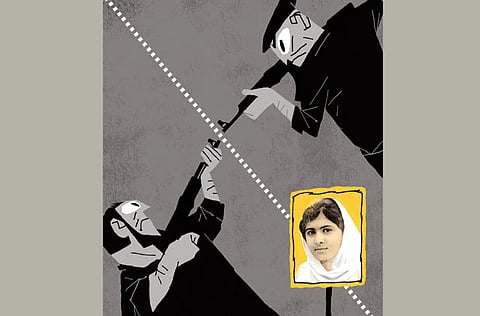

What happened to her was against all human emotion. But now Malala has become a symbol of Pakistan. She is a role model, someone who stood up for education at a time when schools were being blown up. The area in which she lived, the Swat Valley, had been taken over by the Taliban, who opposed western education. They thought it was polluting the minds of girls, in particular, and banned them from going to school. Malala opposed this. And for doing so, she was singled out and shot. What the attack on Malala shows us is the sheer brutalisation and radicalisation of Pakistani society. Eight-and-a-half years ago, we were taken into a war by General Pervez Musharraf when he sent the country’s military into the region of Waziristan that borders Afghanistan. That was the beginning of the downward spiral.

Until then, we had no militant Taliban in Pakistan, although we did have sectarian militant groups, created during the Afghan jihadist movement in the ‘80s by Pakistan’s Inter Services Intelligence (ISI) and financed by the CIA. It took two years, from 2004 to 2006, for the creation of the Pakistani Taliban. Today, under the generic name of Taliban, there are six different types of militants who are fighting against the Pakistani state — and it is crucial to understand who and why.

First, there is the ideological Taliban, who want to set up a state based on their concept of Sharia, enforced through the barrel of a gun. This group makes the religious parties involved in politics in Pakistan look moderate. But it is very important to know that when the Taliban were in power in Afghanistan (1996-2001), there were no takers for their ideology in Pakistan, not even in the tribal belt on the Afghan border. I maintain that this particular ideology of Taliban is a tiny proportion of the extremists.

The second militant group under the Taliban are Pashtun nationalists. While the tribes of this ethnic group often fought each other, they have, throughout history, always united to resist foreign invaders. The British had 80 years’ experience with the tribal Pashtuns, leaving behind a rich history of interaction with them. In Pakistan’s 2002 elections, the coalition of religious parties called the MMA swept the entire Pashtun belt because it condemned the Nato invasion of Afghanistan. Just as in the British and Russian invasions, when Nato invaded there were Pashtuns who united to join the resistance, calling themselves Taliban.

Then there is a third group — remnants of jihadist organisations who were brainwashed to believe that fighting the Soviet occupation was a religious duty. They were controlled by the Pakistani establishment — until the moment Pakistan sided with the American war on terror. Many rebelled against the establishment and started calling themselves the Punjabi Taliban.

The next group is a product of the massive collateral damage that has occurred in the tribal areas as a result of drone attacks and Pakistan army’s operations. Those affected picked up arms because, according to the Pashtun tradition, revenge is an integral part of the code of honour. When family members die in a bomb attack, a Pashtun will look for revenge by joining the militants. This was brought home to me by the case of Jaffar Masud, who was studying electrical engineering at Namal College, a university I set up, affiliated to Bradford University. When Jaffar heard that family members had been killed in a drone attack, he left his studies, went all the way into Afghanistan and blew himself up on a Nato convoy at Gazni. There are many examples of tribal people turning to the Taliban because their family members have been killed by drone attacks. In fact, a total of 172 innocent children have had their lives cut short by these attacks.

And then there are those who have picked up arms because they feel the American war against terror is a war against Islam. This was confirmed by a Gallup survey carried out in the Muslim world, where the vast majority felt that it was not a war against terror but a war against Islam. This belief will always produce highly motivated young men who are willing to die for their religion.

When asked about the women and children that his attack might have killed, Faisal Shahzad, the failed Times Square bomber, told the judge that drones kill women and children, too.

Lastly, because of the massive destruction in the tribal areas after nearly a decade of military operations and drone attacks, the economy has collapsed and there is an army of young unemployed who have picked up arms and are involved in the only business going — kidnapping for ransom.

Unless we address these very different groups and understand their motivation, senseless military operations will push all of them together, create yet more collateral damage and increase terrorism in Pakistan. We will be looking at a never-ending war. So what is the solution?

Number one — Pakistan must disengage from the American war on terror. Pakistan needs to stop taking aid from the US, because this immediately links us to America and it strengthens the extremists’ cause. Number two — Pakistan needs to stop the drone attacks. They are brutal and violent and only perpetuate the frenzy of fanaticism. Number three — Pakistan must win the people of the tribal areas to its side. The secret to peace lies with these people. The moment we convince them that Pakistan is not fighting America’s war, the militants will no longer have the narrative to justify their fighting against the Pakistan army and security forces. These are the stakeholders and they are sick of this war.

This is the same reason the Americans and the British cannot win in Afghanistan. The population is providing logistical support and recruits to the militants. That is how they can survive. You have to isolate the extremists. Unfortunately, Nato is making the same mistakes as the Pakistani army — when you use artillery and gunships on defenceless villages, you end up losing the battle for hearts and minds. If a military strategy is used, it must be part of a larger peace strategy that involves — not alienates — the people of the area. After starting a dialogue with the tribal populations, there must also be truth and reconciliation. People have suffered tremendous losses and need support. A fraction of the money that is being poured into these bombs should go into development and helping people to rebuild their lives. Unfortunately, the Pakistani government lacks credibility. It has no strategy. It attempts the same thing over and over again and is somehow surprised when it gets the same result. We have to do something different. I have been saying this for more than eight years. I have been labelled a Taliban apologist and a terrorist appeaser. I feel hemmed in by both sides. But things have gone from bad to worse. The surge of sympathy around the world for Malala has been incredible. But what happens next? Because of the huge anti-Taliban feeling, everybody wants blood. Is that really going to solve anything? In the midst of this understandable anger, we should start trying to find a peaceful solution, not another military one. Violence will only be met by more violence. After all, what would Malala want?

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London, 2012

Imran Khan is the leader of Pakistan’s Tehreek-e-Insaaf party.