Engaged citizens take the US to task

The Open Society Justice Initiative’s latest study is an indictment of US policy

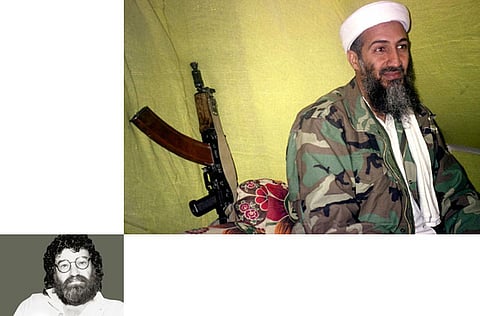

The film did not, to be fair, hold a brief for the use of torture, but it did impute a measure of efficacy to it in the hunt for Osama Bin Laden. Zero Dark Thirty, the critically acclaimed film by Kathryn Bigelow — who had directed the 2008 The Hurt Locker, set in Iraq during America’s bloody war there — is already on over 200 top-ten lists. Since its release recently, Zero Dark Thirty has won a host of awards, including Best Actress, Best Picture, Best Screen Play and Best Film Editing.

Yet, at the Oscars, an event that will be watched by ten times as many people as had watched President Barack Obama’s State of the Union address, Zero Dark Thirty will not come up with a sweeping success. The reason? It is doubtful that a liberal-leaning Hollywood will honour a director who appears to imply that without torture, and torture alone, Osama Bin Laden would still be floating around. Several social critics, who take cinematic art seriously, have called Begelow an apologist for the government’s harsh interrogation techniques, a “torture’s handmaiden”, likening her to Nazi propagandist Lani Riefenstah, of Triumph of the Will fame.

But wait, Zero Dark Thirty (the reference is to 30 minutes past midnight, the time the US Navy SEALS raided the Al Qaida leader’s compound) is only a movie. Film studios produce movies that merely dramatise real events in the real world, that tantalise our visceral need for entertainment. Where they probe, it is by allusion.

For our cerebral needs, however, we seek to read thoughtful, well-researched reports by respected watchdogs whose business is to stand guard over acts of malfeasance by governments. These reports may not match the fun we derive from watching a gripping cinematic production on a large screen in a darkened movie theatre, but they are necessary when a democratic polity decides, somewhere along the line, to untether itself from the rule of law — as the US has done in its rush to exact revenge for 9/11.

And this is where the Open Society Justice Initiative (OSJI) comes in. Does the name ring a bell? If it doesn’t it is because OSJI, established several years ago by the liberal billionaire George Soros, works on the quiet and shuns flashy publicity. It operates effectively on many continents where it promotes democratic governance, human rights, social reform and freedom of information. Its reports are read avidly by those who want to see to it that governments that overreach their mandate, or break the law, should be taken to task by their engaged citizenry. That OSJI derives its name from Kark Popper’s iconic book, The Open Society and its Enemies, is no coincidence.

The Initiative’s latest study, Globalising Torture: CIA Secret Detention and Extraordinary Rendition, may not have a lot new to say about the subject for those of us who have followed it over the last decade, but the crisply composed, 216-page document is a definitive wrap, as it were, for that dreadful chapter in modern American history.

It is no secret of course that following September 11, 2001, the US embarked upon a highly classified programme of secret detention and extraordinary rendition of suspects, who were flown to countries that used torture with facile ease and with nary a look over their shoulder, or who were held in dreadful “black sites” all the way from Poland to Thailand. and subjected to, well, shall we say — if you will pardon the CIA euphemism — “enhanced interrogation techniques”. (the Washington Post’s investigative reporter, Dana Priest, broke the story about the sites in 2006.)

A great many of the detainees, it later transpired, were, sadly, cases of mistaken identity. In a landmark ruling, on December 13 last year, for example, the European Court of Human Rights, vindicated the long search for justice of Khalid Al Masri, a German citizen, victim of a mistaken rendition operation by the CIA, who was snatched off a border crossing in Macedonia and flown to Kabul on a CIA aircraft, where he was held for four months at the notorious detention centre known as the Salt Pit — as were the cases of Maher Arar and Abdullah Al Maliki, both Canadians, who were rendered respectively to Syria and Egypt. And the less said about what awaited them there the better. The Initiative study documents the ordeal of a mere 136, out of hundreds of other victims, and lists as many as 54 foreign governments, including several in the Arab world, that collaborated, in one form or another, with the US.

The Initiative’s purpose in releasing Globalising Torture? It is, as the introduction states, to “make it clear that the time has come for the United States and its partners to definitely repudiate these illegal practices and secure accountability for associated human rights abuses”.

The study has already caused a stir among those, individuals and institutions alike, who feel that it is about time the US owns up, ceases and desists. In an editorial last Monday, the New York Times called the OSJI judgements “an important condemnation of CIA tactics under the Bush administration”. But, it added: “They are also a warning to Obama that pressure for the United States and its partners to acknowledge and make amends for gross violations of international legal and human rights standards is unlikely to subside.”

In this context, the debate over Zero Dark Thirty and whether it will win an Oscar or two at the Academy Awards night, becomes of nebulous concern.

In May 2011, the body of Osama Bin Laden was delivered to sailors standing on the dock of the USS Karl Vinson in the Arabian Sea. Reportedly, the body was washed and wrapped in a burial shroud according to Islamic tradition. After weights were attached to the corpse to ensure it would never rise in the water, it was tipped over into the ocean where it silently sank to the bottom.

That was the end of Bin Laden. It is not, well over a decade after 9/11, the end of the debate over America’s disgraceful violation of international law in its ongoing, overly zealous “war on terror”. In the US, lest it be forgotten, the government is answerable to its citizens.

Fawaz Turki is a journalist, lecturer and author based in Washington. He is the author of The Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile.