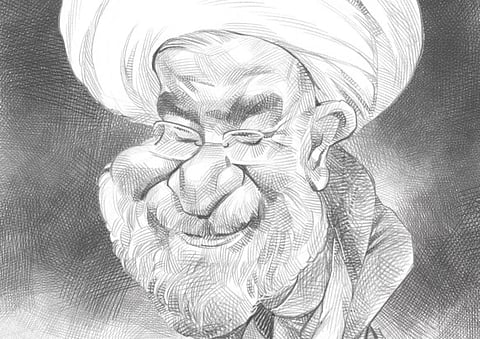

Don’t pre-judge new Iran president Hassan Rouhani

Foreign politicians are sceptical of seeing any real change in substance from that of his predecessors

Is Iran’s new president, Hassan Rouhani, a breath of fresh air, promising a new start for the Islamic Republic? Or does he offer a different style from his predecessor, Mahmoud Ahmedinejad, but no real change in substance?

The honest answer to this question is: ‘no one really knows,’ but that has not stopped pundits of all stripes from issuing seemingly definitive judgements of the (days old) Rouhani presidency. Indeed, many analysts seemed comfortable writing the history of Iran’s incoming administration weeks before it began.

Since his election, Rouhani has called for new engagement with the outside world. He has also vowed that his country will not surrender to international sanctions. Depending on your point of view these remarks can be seen as either an evil attempt at obfuscation or a prudent effort to tend to public opinion at home without limiting one’s options.

When Iran’s Guardian Council disqualified most of the hundreds of candidates who sought to run for president, Rouhani and the handful of others who survived the vetting process, were widely dismissed as extremists. When he won (unexpectedly, at least to outside observers) he was hailed as a ‘moderate’ and a ‘reformist’ — even by some who only a few weeks earlier had declared that the approved slate of candidates contained no reformists at all.

What all this really indicates is a lot of wishful thinking on both sides. I do not claim any particular expertise in Iranian politics, but it is worth remembering that, as a rule, politicians ascending to their country’s highest offices do not always act in predictable ways.

When Ahmedinejad was first elected the widespread assumption among outside observers was that his unexpected success was evidence of a desire (among voters and regime insiders alike) to turn inward. Eight years earlier the election of Ahmedinejad’s predecessor, Mohammed Khatami, was widely viewed as the beginning of a sea-change in Iran’s relations with the West. In office, neither man performed as expected.

To be fair, Rouhani is not quite the blank slate that his two predecessors were. Prior to his presidency Ahmedinejad was the mayor of Tehran. Khatami was a former Minister of Culture who, at the time of his election, served as the head of Iran’s national library. Rouhani was a longtime aide to the Islamic Republic’s founder, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and, later, to Rafsanjani; a parliamentarian and chief nuclear negotiator. He is, in short, well-known to the sort of Western officials who spend their days keeping track of Iranian foreign policy. Though a cleric by training, Rouhani also has a secular education both in Iran and abroad (he holds a degree from a Scottish university).

A few years from now any or all of those biographical details might prove to be significant. For now, each is tantalising in its own way. Does any of this mean that Rouhani’s actions as president can be predicted with any degree of certainty? I’d say not, but there are a lot of foreign politicians who beg to differ.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has urged the international community not to be “lulled into complacency” by Rouhani’s victory (a remark that former British foreign secretary Jack Straw called “unthinking and self-defeating”).

California congressman Ed Royce argued that the election of an apparent moderate to Iran’s presidency was, itself, reason to take a harder line with the country: “Iran may have a new president, but its march toward a nuclear programme continues. The economic and political pressure on Tehran must be ratcheted up,” he said.

Last week, before Rouhani even took office, the US House of Representatives voted 400-20 to broaden US sanctions on Iran (the margin is significant because it indicates that knee-jerk views on Iran are not a partisan issue in Washington).

It is hard to look at all this and not think that some Western politicians fear a more flexible Iranian leadership. For some this goes far beyond the nuclear programme. They want to change the country’s entire political system. If you believe your opponent to be inherently evil then any leader who talks about compromise is, at best, a dangerous distraction

Right now that view can be seen among numerous commentators and media outlets, mainly (though not exclusively) in the United States. As a mindset, it starts from the presumption that Iran is so evil it does not matter who is in charge.

Where does the truth about Rouhani lie? Perhaps we should all wait and see. Pre-judging risks turning our worst fears into self-fulfilling prophecies.

Gordon Robison, a longtime Middle East journalist and US political analyst, teaches political science at the University of Vermont.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox