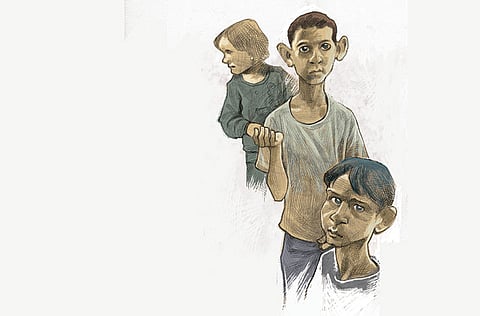

Despair of the Syrian beggar boy

In Beirut, children begging or peddling items is now a common sight

It was 2am and 11-year-old Khalid moved alone through the crowds of drinkers and smokers that had spilled from the bars on to the Beirut street. The thin boy could barely be heard above the pounding music of the disc jockeys and raucous chatter. “May God keep you, please help,” he asked customers, the palm of one small hand raised in the air. Most turned their backs, or shooed him away. But his family will not eat if he earns nothing and so he cannot stop. He finishes work only when the bars are empty, usually at 4am, and catches a few hours sleep in a nook beneath a concrete ramp in Beirut’s central bus station.

Khalid is one of countless child refugees whose parents, unable to make ends meet in Lebanon after they fled the conflict in Syria, have turned their children on to the streets to work. Lebanon has the highest concentration of refugees anywhere in the world, with one million Syrians now swelling the population of four million. But with no refugee camps, little government infrastructure and aid agencies that are chronically underfunded, most newcomers are forced to fend for themselves.

One in 10 Syrian child refugees are now working across the region, according to Unicef, the child agency. In Lebanon more than half of the Syrian refugees are children. “Lebanon has the highest number of child refugees from Syria, and also the largest proportion of children who are working on the streets,” said Juliette Touma who works with Unicef.

“The reason is that more and more families are running out of savings and so they are sending their children to work.”

Some work in fields, farms or factories, picking up whatever meagre wages they can earn. But with the economy struggling and the number of unskilled workers steadily growing, an increasing number of children are being forced to try to make a living on the dusty streets of the Lebanese capital.

Khalid’s life was not always like this. Before the war, he lived in a large home in the central Syrian city of Idlib with his sister and parents. He spent his days in school and playing with his friends. “I didn’t particularly like school but I like my friends,” he said. “We played on our computers, or ball games like football.” One year ago, when rebel groups attacked the area near their home, the family fled to Tripoli, in northern Lebanon. His father was unable to find work, and his mother, a diabetic, had to stay at home to nurse Khalid’s newborn brother. Last month things became even worse when Khalid’s father became yet another casualty of his country’s brutal civil war.

“He went to Syria to get bread because we were hungry,” said Khalid, who was too upset to explain why such a journey was needed. “A sniper shot him in the head.”

No vivacity for a boy his age

Desperately needing money, Khalid was put on a bus to Beirut. Every day he travels the two hours to the capital city alone and works through the night to keep his family alive. “I have to make 20,000 Lebanese pounds (Dh47.95) every day,” said Khalid.

“I take it to my mum. One time I didn’t make any money. She didn’t beat me, but she had to borrow money from others so she could pay the transport to send me back to Beirut.”

Khalid said he begs because it makes more money than selling chewing gum. “I tried to be a shoeshine boy, but I didn’t like it at all. You work hard for nothing. People give you 250 Lebanese pounds.”

Khalid was well dressed in cream corduroy trousers and matching blue hoodie and sneakers, but his hands and face were black with the dirt of sleeping rough. He has none of vivacity expected in a boy of his age. All sense of fun, and joy for life has been sucked out of him. His life now is one of survival, of remaining detached whilst going through the motions needed to support his family.

He has one friend, a 12-year-old Syrian boy, who is also called Khalid, and who works as a shoe shiner on the same street. Khalid showed The Sunday Telegraph the place where they both sleep. Arriving at the city’s central bus station — a massive concrete structure, whose floors and walls are black with exhaust fumes, he ran up two staircases that were thick with grime and litter. The air was rancid with the smell of urine. On an empty top floor, pieces of cardboard and aluminium were laid out under a concrete bus ramp. “There are 10 people who sleep here. All of them sell gum or flowers or beg,” said Khalid.

In the Lebanese capital, children begging or peddling gum, tissues or roses are now a common sight.

They toil for hours under hot sunshine, standing at busy intersections or trawling bars and cafes. Sometimes, if the police see them, they are detained and thrown in a prison cell. Most of those are released to the Home of Hope, a centre run by a Christian non-profit group to help child labourers.

The centre existed before the war, but numbers have swollen since the conflict in Syria began, explained Maher Tabarani, the home’s director.

“We have 70 beds for the children and they are all full. Yesterday the police brought three children to us, but we had to turn them away.”

Arriving at Home of Hope the children are washed, and given the attention of a child psychologist. The centre has an on-site school. Almost all of the children suffer deep psychological trauma. “Forget what happened to them in Syria,” said Tabarani. “In Lebanon the kids are beaten, sold into prostitution rings, forced to sell drugs. Some parents rent their infants to older street sellers. The peddlers know they’ll make more money if they are carrying a baby.”

Two thirds of the children who come to the centre had been sexually harassed, said Tabarani, adding that the children were being bought for sex for “a dollar or two”. The courts in Lebanon, ill-equipped to cope, rarely intervene. Parents come to collect their children from the centre, and next day they are back on the street working.

Noah George, who works at Home of Hope, said: “You don’t know what you are working for. You try to help and then the child starts to get better. Only to then be back on the street.”

One of these children is 10-year-old Mohammad who works the corniche with his cousin Eisa, nine. Together they try to sell roses and gum to passers-by on the seafront. Mohammad wears a grimy pyjama top emblazoned with Spiderman. He arrived with his parents in Lebanon one month ago when they fled Yarmouk, a district of Damascus that has seen some of the heaviest fighting.

“My mum told me to come here and sell roses. I have to sell 10 every day,” said Mohammad. Already caught once and taken to the Home of Hope, he has clearly been told not to let it happen again.

“My mum will kill me,” he said when The Sunday Telegraph asked to meet his family. “I am not allowed to show anyone where we live.” After selling his last rose as dusk fell, he ran down the street and leapt on to a bus home.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox