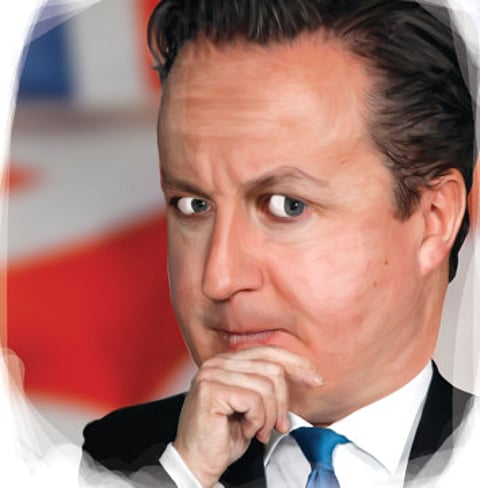

David Cameron buckles under pressure — again

Recent press law issued showed British prime minister is paying price for not committing to fixed positions

Years from now, David Cameron will look back with mystification at how his premiership got bogged down in the theology of newspaper rights and responsibilities. He entered parliament with a magisterial lack of interest in the press. A career in television had left him suspecting that only broadcast media really influenced politics, a view that hardened when he won the Conservative leadership with scant support from print outlets.

In his early years as leader of the opposition, he was a refreshingly reluctant schmoozer of editors and proprietors, usually delegating the chore to colleagues. Some around him even harboured plans to smash open the “lobby” system of political journalism, with its privileged briefings and restricted access.

Then Cameron did something he does too often: He buckled to political pressure. In 2007, as Tories began to revolt against his modernisation of their party, he hired Andy Coulson, who presided over phone-hacking at the News of the World, to bring a grittier conservatism to his team. Four years on, when the tabloid closed in disgrace and Cameron’s intimacy with its owners drew criticism, he hurriedly launched an inquiry under Lord Justice Leveson with a capacious remit to probe press conduct.

Both of these capitulations earned him short-term relief, but they also brought him to his present fix. He finds himself burdened with the absurd task of deciding the future of the press, forced against his instincts to accept some measure of statute in policing journalistic malpractice. He is cursed as a fair-weather friend by victims of newspapers and by newspapers themselves and snubbed by his Liberal Democrat coalition partners as they make common cause with the Labour opposition.

It is the last of these torments that is most ominous for Cameron. If the next government turns out to be a coalition of the Lib Dems and Labour, the saga of press regulation might be seen as its genesis. The two parties have scowled at each other since 2010, when the Conservative-Lib Dem administration was formed. Many in Labour somewhat grandly used to let it be known that they would only ever govern with the Liberal Democrats if Nick Clegg stood down as their leader. Ed Miliband, the Labour leader, even refused to share a platform with him as they campaigned for electoral reform in 2011.

The rapprochement under way is remarkable, therefore, and has only little to do with the parties’ actual views on press regulation. Like peace talks after a war, it is the very process of dialogue that is thawing relations.

The Lib Dem leader has been working “eyeball to eyeball” with Labour politicians on the issue, according to someone privy to the conversations. They have realised that Clegg, who is easy to dismiss as lightweight and double-dealing, is intelligent, business-like and tough.

The news that Labour politicians are revising their low opinion of Clegg will not surprise senior Tories, who mocked at him in opposition only to lament his effectiveness at getting his way in government. But it should perturb them, as should the alacrity with which Clegg spun last Monday’s agreement on press regulation as a victory for himself and Miliband against the prime minister.

If the next election results in a hung parliament — still the most likely outcome, despite Labour’s current poll lead — there will be few obstacles to a red-yellow deal. Until now, Clegg’s determination to remain leader of his party beyond 2015 has been interpreted as a problem for Labour, not least by Labour themselves. Their self-pitying notion that he chose to govern with the Tories out of brazen ideological choice is giving way, as the wounds heal, to a grudging, unspoken recognition that cold parliamentary arithmetic limited his options.

Even the sincerest point of discord between the parties in 2010, which was fiscal strategy, will not be so acute the next time if — as many suspect — Labour promises to match the government’s spending plans for the years beyond 2015. Labour and the Lib Dems are also close on Europe, the other issue likely to dominate the next parliament.

If policy is not a fundamental hurdle to a Clegg-Miliband alliance, then that leaves only personal compatibility, which is what is improving almost daily. At times, it is only the fundamental reasonableness of senior coalition figures — Cameron, Clegg, George Osborne, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Danny Alexander, Chief Secretary to the Treasury — that keeps this government together. However, Miliband (unlike, it is fair to say, some of his Labour colleagues) has that virtue too. Meanwhile, Cameron’s periodic sops to his right — another case of his propensity to cave in to pressure — makes it easier for an avowed centrist such as Clegg to justify his infidelity.

The prime minister is wrongly believed to be hopeless at strategy. The truth is that he is anti-strategy. He thinks committing to fixed positions and planning for the long-term are follies; he keeps his options open and makes faint adjustments to day-by-day events. This has been his approach to the press since the day he appointed Coulson. Its shortcomings are now unmistakable.

— Financial Times